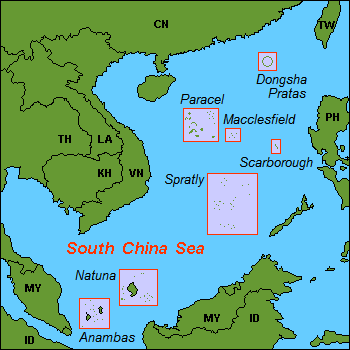

Recently, news broke out about the Philippine news team’s vessel being chased by Chinese authorities as they aim for the Mischief Reef to conduct an investigation after the report of the presence of the Chinese vessels in the Julian Felipe Reef and the continued construction of Chinese infrastructures in the artificial islands in the disputed areas of the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea. The Chinese authorities that warned them include missile boats within the 90 nautical miles from the island of Palawan. The disputed area in the South China Sea is until now in a melting pot concerning not just the Philippines but also with the rest of Southeast Asian countries. With the atrocious steps taken by the Chinese post a threat in the country’s economic stability, much less to its national security.

LOOK: An overview of fishing vessels spotted in the Julian Felipe Reef on Tuesday, March 23. The Philippine Coast Guard spotted about 220 Chinese fishing vessels in the area earlier this month. Satellite images by Maxar Technologies via Reuters from r/Philippines

China’s interventions in the South China Sea were driven by both economic and dominating forces. In 1995 president Jiang Zemin highlighted that China was not occupying the Mischief Reef in Spratly Islands but building shelter for their fishermen, however, in 2002 and 2005, it became a military garrison. Recently, Pres. Xi Jinping released the same statement. He asserted that they’re building hubs for their fishermen. The Mischief reef is the nearest reef of the Spratly island to Palawan. Whilst the negotiations over the Mischief Reef in 1995 have met with some success, the primary issues remain unresolved (Storey,1999). This has however become worse with the recent arbitrary violations of China in the disputed area. After building artificial islands in the Spratlys, Chinese vessels are robbing around the Julian Felipe Reef (with the Chinese name Niu’e Jiao) claiming it as part of their Nansha Islands as asserted by the current Chinese Foreign Ministry, Zhao Lijian.

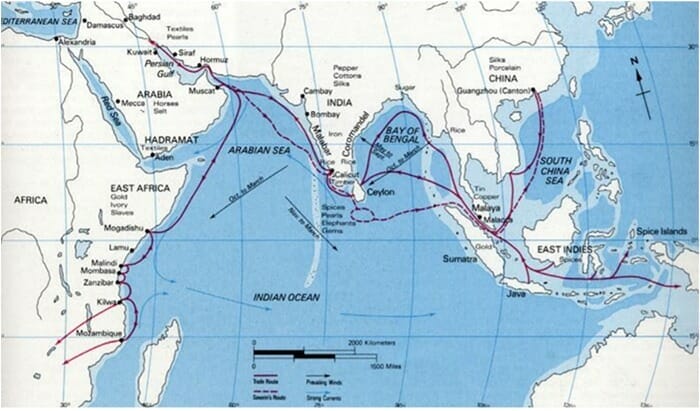

The territorial disputes committed by China were not intended for its economic power but the establishment of its long-awaited plan, the ‘China’s Grand Strategy’ or ‘Deng Xiaoping Moment 2.0.’ Scholars call it as ‘China’s maritime renaissance’ and ‘A Great Leap Outward.’ It includes the aim of resurrecting the ancient Silk and Maritime Silk Route (MSR) that would connect China to ports in the Indian Ocean (or lands above the wind) and Malacca, South China Sea, Java Sea, and further east (or lands above the sea).

The Proposed MSR

Image: Seaceramic.org as cited by Chaturvedy (2014)

The idea of the MSR was outlined during Li Keqiang’s speech at the 16th ASEAN-China summit in Brunei, and Xi Jinping’s speech in the Indonesian Parliament in October 2013. President Xi Jinping updates the spirit of the ancient Silk Road by calling for the joint development of an economic belt along the Silk Road and a Maritime Silk Road of the 21st century. The main emphasis was placed on stronger economic cooperation, closer cooperation on joint infrastructure projects, the enhancement of security cooperation, and the strengthening of maritime economy, environment technical and scientific cooperation (Chaturvedy, 2014).

China’s Grand Strategy was summarized by Chaturvedy (2014) in three outlines: acquire ‘comprehensive national power’ (CNP) essential to achieving the status of a ‘global great power that is second to none’; gain access to global natural resources, raw materials, and overseas markets to sustain China’s economic expansion; pursue ‘three Ms’: military build-up (including a naval presence along the vital sea lanes of communication and maritime chokepoints), multilateralism, and multipolarity; and build a worldwide network of friends and allies through ‘soft power’ diplomacy, trade and economic dependencies via free trade agreements, mutual security pacts, intelligence cooperation, and arms sales.

South China Sea

South China Sea as the perfect spot for the attainment of this long-term goal, plays an integral role in the region’s military affairs, in political development, economic growth, and cultural change. Thus, South China Sea could be a haven for naval forces (for prestige) and sea allows naval ships to reach distant countries and makes a state possessed of sea power the neighbor of every other country that is accessible by sea. The MSR aims to seize the opportunity of transforming Asia and to create strategic space for China (Chaturvedy, 2014).

The Maritime Silk Route (MRS) that China is remapping is based from the ancient trade route from East Asia, to Southeast Asia, India, and Arabian Peninsula. The Ancient Silk Route dated back from the Tang dynasty had been a major channel of communication, through which ancient China made contacts with the outside world. What is remarkable about it, is it remained a peaceful means of inter-state commercial activity and inter-ethnic cultural exchange. The ancient MSR did not lead to wars and strife, much less colonialism and imperialism in Asia even without the presence of the United Nations Conventions on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Contrary to this situation, Chinese establishment of infrastructure and territorial expansion has become a threat to other country’s security. In the 2014 Pew Research poll, majorities in eight of the 11 Asian countries surveyed are worried that China’s territorial ambitions could lead to military conflict with its neighbors. In the number of nations closest to China, overwhelming proportions of the public expressed such fears, including 93% of Filipinos, 85% of Japanese, 84% of Vietnamese and 83% of South Koreans. Moreover, 61% of the public in the Philippines and 51% in Vietnam say they are very concerned about a possible military confrontation with Beijing. And, in China itself, fully 62% are concerned about a possible conflict (Pew Research Center, 2014).

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was established in order to carry out China’s Grand Plan. It is used as a counter attack to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) which was originally dominated by Japan and the US. Its primary aim is to provide a strong investment and financing platform for multimodal connectivity, like building high-speed rail, ports, airports, within related countries and allocated US$ 100 billion as its capital (Chaturvedy, 2014). Furthermore, the Philippines signed in 2014 as its one of the founding members despite its reluctance due to territorial disputes. According to Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), the Philippines has a total debt of US$ 756 billion as of December, 2020. Chaturvedy (2014) asserted that this could be a soft power mechanism of China to influence its neighboring countries for its proposed MSR plan.

In conclusion, the idea behind the remapping of the ancient silk routes (in the North and the SMR) were based on its ancient ideals of promoting peace, connectivity, free trade, and cultural diversity. It seems like these ideals are much of the frontlines for its economic and world domination in the 21st century. Countries surrounding the South China Sea were babbling for its continuous bullying by its authorities in the disputed territories. These countries have already asked help from the international organizations to settle their disputes with China. In fact, the Philippines has sent three diplomatic protests in the UN for the presence of the Chinese vessels in Julian Felipe Reef but it seems like its protectorates have been vigilant to take necessary steps for the possible worst events that might happen if not taken seriously. The future is uncertain, but if these atrocities may continue to arise, it will cause a domino-effect to the rest of the world.

Jeanel C. Gregorio

Reference:

“Chapter 4: How Asians View Each Other. 2014”. Pew Research Center. Retrieved on April 9, 2021 from: pewresearch.org/global/2014/07/14/chapter-4-how-asians-view-each-other/

Chaturvedy, Rajeev Ranjan. (2014). New Maritime Silk Road: Converging Interests and Regional Responses. ISAS Working Paper. Institute of South Asian. Studies National University of Singapore. PDF.

“China’s Maritime Disputes: 1895-2020”. (2021). CFR Timeline. Retrieved on April 9, 2021 from https://www.cfr.org/timeline/chinas-maritime-disputes

Maxar Technologies. (2020). LOOK: An overview of fishing vessels spotted in the Julian Felipe Reef on Tuesday, March 23. Retrieved on April 16, 2020 from: https://www.reddit.com/r/Philippines/comments/mcnqi6/look_an_overview_of_fishing_ve ssels_spotted_in/

Storey, I. (1999). Creeping Assertiveness: China, the Philippines and the South China Sea Dispute. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21(1), 95-118. Retrieved on April 9, 2021 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25798443

Total Philippine External Debt. (2020). Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. Retrieved on April 9, 2021 from: https://www.bsp.gov.ph/statistics/external/tab5b_exd.aspx