Shan State, Myanmar: Three weeks ago, China took the Western world, specifically Washington, by complete surprise when the senior Chinese Communist Party official Wang Yi emerged in Beijing to announce that Beijing had successfully brokered a historic peace deal between the two erstwhile enemies, Iran and Saudi Arabia. China’s point man was flanked by the representatives of the two countries.

On “What are the implications of the Saudi-Iranian diplomatic deal?” Al Jazeera Inside Story, Hillary Mann Leverett, CEO at political risk consultancy Stratega in McLean, Virginia, went so far as to characterize China as “the (new) indispensable nation” in the Middle East, the energy-strategic region where the United States has for over decades perceived itself as the sole mover and shaker. Indeed, while Washington is busy with its proxy war against the Russian Federation in Ukraine and consumed by its concerns over the Taiwan Strait, China has emerged as the winner.

A crucial customer of both Saudi and Iranian oils, China was able to broker a peace deal between the region’s two old adversaries, which agreed not only to re-establish diplomatic ties but also to reactivate a lapsed security cooperation pact … as well as older trade, investment and cultural accords,” according to the New York Times.

Among Myanmar watchers, the news from the Middle East has reignited an interest in China’s mediating role in Myanmar’s conflicts which have been raging on for decades and have intensified since the universally unpopular coup of February 2021 by Min Aung Hlaing.

FORSEA co-founder and a long-time Burmese dissident Maung Zarni told this author that “China should be playing an effective peace-mediator role in Burma, instead of simply pursuing a narrow set of its own economic and geopolitical interests. This approach will not succeed, nor will it serve the interests of Myanmar people.”

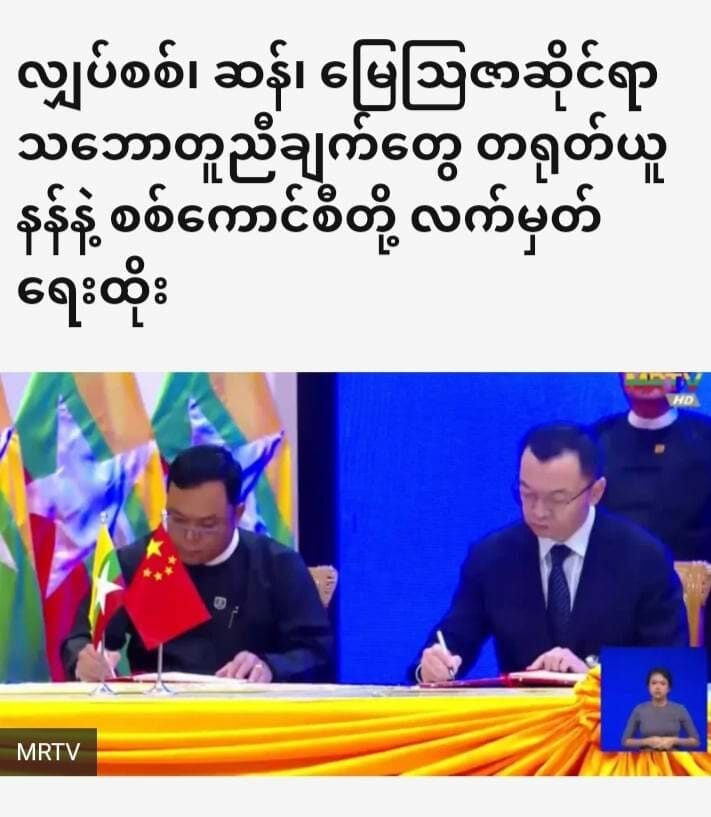

A Myanmar military representative and the representative of Yunnan Provincial Government signing an agreement regarding the procurement of rice, electricity and fertilizer, a screengrab from Myanmar TV News, 2 April 2023.

In its southern backyard of Myanmar, China shares over 1,000 miles of borders with its Burmese neighbour, yet Beijing’s approach to peace and stability is incoherent and deeply unpopular with the public in Myanmar. For the Chinese Communist Party is not seen as an honest broker, but rather as an external actor, which favours the status quo, that is, the popularly rejected military regime in Naypyidaw.

Beneath the surface of its official rhetoric of non-interference, Beijing is using all its leverage to reshape Myanmar to suit its economic interests and geostrategic agendas. For leverage, China uses the Federal Political Negotiation Consultative Committee (FPNCC) made up of 7 ethnic armed groups in bases alongst the Sino-Burmese borders as its le. They are the UWSA, Kachin Independence Army, National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), Shan State Progress Party (SSPP), Arakan Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army.

China’s approach to “peace mediation” is hardly inclusive. Instead, Beijing focuses on stability in areas directly linked to its economic interests and energy security (such as the twin-gas and oil pipeline which originates in Myanmar’s conflict-soaked coastal region of Rakhine where the genocide of Rohingya took place).

Map indicating locations of People’s Republic of China and Myanmar and their borders. Wikipedia Commons

The emergence of a multi-party democracy within the framework of a federalist state, a popular cry among Myanmar’s multi-ethnic public, is not a concern for China’s foreign policy-makers although such a political arrangement is widely seen as the only way to bring an end to Myanmar’s 7-decades of political strife and violent conflicts and put the country on the path towards lasting stability.

Since the military coup of 2021 which ousted the government of Aung San Suu Kyi, China is believed to have focused on preventing the coup junta from dissolving her National League for Democracy (NLD). So, when the junta’s Election Commission announced the dissolution of the NLD and 39-other political parties, including the second largest political party, the Shan National League for Democracy, which won seats in the 2020 elections, Beijing’s consent was assumed to be a key factor.

According to the sources close to Naypyidaw, the newly established State Administration Council or SAC, the coup regime, was poised to outlaw the NLD after having rounded up hundreds of party leaders, including Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and her notional President Win Myint. But it was China that had initially prevented the dissolution of NLD.

But two years on, Beijing’s stance has changed.

The Chinese have to view the NLD as a spent force, with clear indications of implosion within its central executive committee. Additionally, Beijing sees the refusal of the NLD leaders who are not in captivity to re-register the party in preparation for the next round of elections announced by the coup regime as a “real problem.”

One Beijing-based Chinese analyst on Myanmar affairs said to this author, “the Ethnic Resistance Organizations (EROs) are losing political relevance”, in the eyes of Chinese policymakers.

Besides, the National Unity Government (NUG), made up largely of staunch Aung San Suu Kyi loyalists, are seen not representative of the entire NLD leadership.

Worse still, Beijing views the NUG as a stooge of the United States, and hence will not accept the government made up of “American lackeys” in its important backyard. Chinese officials have been explicit with their view that the NUG opening an information office in Washington is “undiplomatic” (that is, not strategic or smart). Finally, China is said to be concerned about the enactment of the Burma Act, officially known as Burma Unified through Rigorous Military Accountability Act (BURMA Act; H.R. 5497) which US President Joe Biden signed two days before Christmas last year as a part of James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (NDAA 2023; P.L. 117–263).

In response, Beijing has upped its game in Myanmar.

One of the leaders of a Chinese-border-based ethnic armed organizations known as the Northern Alliance, who was in a meeting with China’s Special Envoy to Myanmar Deng Xijun in Kunming, Southern China said to this author, “Although China’s Special Envoy to Myanmar has not explicitly told us to step up our collaboration with the SAC (Myanmar coup regime), it was clear that that was what Beijing wanted us to do”.

Geopolitically and for its energy security, Myanmar’s three states (Kachin, Shan, and Rakhine) are crucial for China. All the afore-mentioned 7 members of the of the FPNCC’s members are based in these regions. According to the sources close to FPNCC, China gives these armed groups security guarantee before the latter entered into talks with the coup junta.

China also urges the FPNCC members to keep a tight control of military movements including force expansions by Myanmar junta along the Sino-Burmese borders. In addition, Beijing pressured the groups away from inter-ethnic group military conflicts, typically driven by territorial expansions as claims and counter-claims over territories are made by different armed groups along ideological, organizational and ethnic lines.

China’s logic here is to keep the FPNCC’s largely well-armed members from getting involved with the majoritarian ethnic resistance groups waging anti-coup military operations in the heartlands of Myanmar. This in effect enables the coup regime in Naypyidaw to step up its brutal scorched-earth military campaigns against any ethnic majoritarian resistance groups away from the Sino-Burmese borders.

As the saying goes, a nod is as good as a wink to a blind horse. The coup junta does not extend its martial law (and military campaigns) to stamp out the community-based people’s resistance movements along the regions where China’s oil and gas pipelines runs through, from Rakhine State’s Kyauk Phyu port in Western Myanmar through the Dry Zone of the Middle Myanmar to Ruili on the Myanmar-Chinese borders.

Perhaps as a show of neutrality on its part, the FPNCC, particularly the United Wa State Army or UWSA, have kept their backdoors open for the pro-democracy National Unity Government. For some members of the FPNCC are said to be lukewarm about China’s push to talk with the coup regime in Naypyidaw. For instance, some of the Northern Alliance (or the Three Brothers) have had bitter experiences with the previous military regimes which initiated the Road Map for Democracy along with their (military’s) national integration or consolidation policies during the 1990’s and 2010’s.

Ta’ang and Kokang ethnic armed organizations have faced enormous military challenges posed by Myanmar military. One organization was disbanded and the other was pushed out from their ancestral region. The Kachin Independence Organization and the Shan State Progressive Party also came under heavy military offensives by Naypyidaw.

But now, all of the 7 ethnic armed groups see the PRC as the only external actor that can mediate their current stand-off with the military junta.

Perception aside, there exists a serious problem with China’s approach to peace and stability in Myanmar, if that.

Beijing has remained opaque in its attempts at restoring stability and promoting peace in its southern neighbourhood. Its Myanmar approach is very much different from its successful approach to decades-old conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

China has pointed to the military’s Constitution of 2008 and the regime-sponsored elections as a framework for resolving conflicts in Myanmar. But the military’s discourse of “law and order” and its anti-democratic and non-federalist Constitution of 2008 is a non-starter, either with the majoritarian ethnic Burmese or non-Burmese ethnic communities, fighting for ethnic autonomy since independence from Britain in 1948.

The elections are an essential component in any multiparty democracy, but they need to be preceded by a broad-based political agreement among all stakeholders who are party to the long-standing conflicts, in a country such as Myanmar with multiple ethnic nations.

China is, as a matter of fact, merely pursuing its economic and geopolitical interests, disguised as a push for Myanmar’s parties in conflict to return to the electoral politics. This push is seen, correctly, as Beijing’s undeclared support for the coup junta in the face of Washington’s support, perceived but not real, to Myanmar’s pro-democracy resistance.

Through China’s jaundiced eyes, Myanmar public’s widespread resistance against the coup regime is tantamount to anarchy. And the Chinese leader worry about Washington’s intervention as Myanmar’s internal strife drags on.

Moreover, China’s economic reopening post-Covid pandemic, GDP growth is deemed a top policy priority for Beijing. And some China watchers see signs of China’s re-focusing on its domestic economic growth reminiscent of the 1990’s.

Towards this economic end, in the near future, China’s approach to Myanmar, however, is likely to be based on Myanmar’s coup regime’s lack of domestic and international legitimacy and changing geopolitical order.

The currently unfolding post-coup conflicts in Myanmar come with geopolitical complications.

Even though there exists no real prospects for any external intervention to bring an end to the protracted domestic conflicts – note the plural – China remains deeply suspicious of Western actors, particularly Washington, “meddling” in what it considers the “internal affairs” of its southern neighbour.

Therefore, China’s latest move in Myanmar is designed to reshape the power balance between the FPNCC of 7-ethnic armed organizations (under Beijing’s sway) and the military junta. Unlike its approach to peace in the Middle East (specifically Saudis and Iranians), China’s approach towards peace and stability lacks any real prospects for peace. For the Chinese are pursuing stability in Myanmar only to the extent it serves to protect their economic, security, and energy interests, not peace for Myanmar as a whole.

Sai Tun Aung Lwin

Sai Tun Aung Lwin is an analyst and researcher from Myanmar’s Shan State, which borders with China, Laos, and Thailand and is a home to various ethnics rebels groups six of which are under Beijing’s sway. An author of several Myanmar language books on Myanmar affairs, Sai Tun Aung Lwin worked as a journalist and analyst covering extensively the Myanmar Peace process and ethnic conflicts for seven years until the coup of 2021.