On Sunday, Myanmar held its first national elections since 2015, when Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) won a smashing victory in the first free and fair national elections in the country in decades. This time around, there were multiple questions about the election, which I raised in a recent piece for World Politics Review. For one, the run-up to the election was not truly fair, as a huge number of Rohingya and people from other ethnic minorities were disenfranchised, and the election was held in an environment in which the Suu Kyi government has cracked down on the free press, and the media environment clearly favored the NLD. Second, there were concerns about whether Myanmar could pull off a safe and relatively high-turnout national election at a time when COVID-19 cases are rising in the country, and Myanmar does not have the resources to effectively protect many voters from the virus. Third, there were questions about whether the NLD would win as decisively as it had in 2015, given that its policies toward Myanmar’s peace process, and other approaches to ethnic minorities, had generally gone over poorly with some ethnic minority groups, who seemed prepared to vote for more locally-based parties. The NLD also was challenged by some new parties started by former longtime NLD stalwarts who had tired of the party’s inability to push toward democracy.

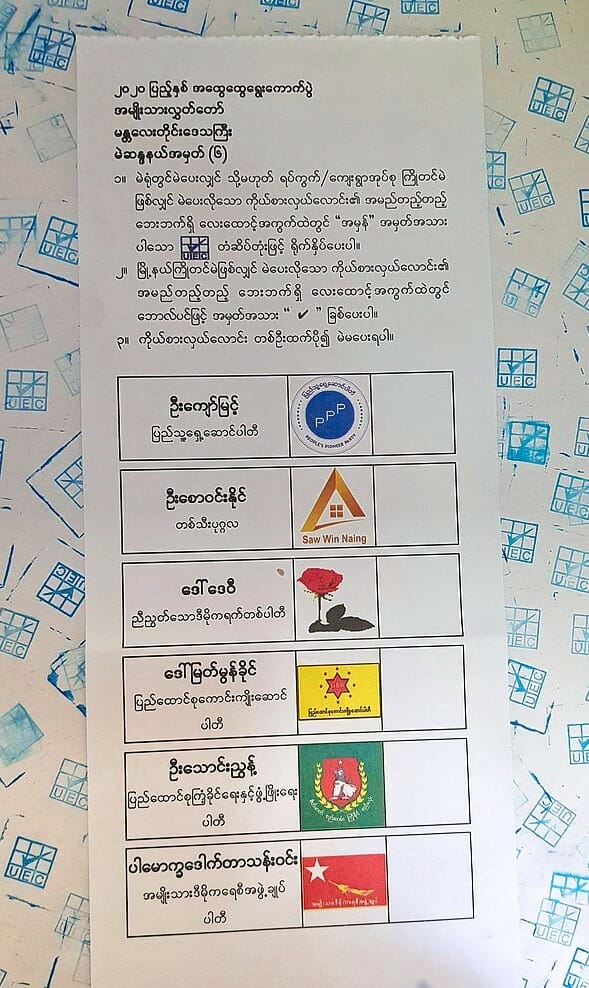

The ballot paper of Myanmar General Election 2020. Wikipedia Commons

Several of these questions seem to have been answered by Sunday’s election; results are coming in, although we do not have anywhere near the full results at this point, and the country’s election commission has not made any formal announcements. The election was held in a relatively unfair environment. Despite international criticism, Suu Kyi’s government did not bend in the days before Election Day. Rohingya remained disenfranchised, as did people from some other ethnic minorities, the NLD continued to allow censorship of rival parties’ websites, the press was primarily for the government, and other distortions remained.

However, Myanmar appeared to be able to hold a safer and high turnout election that many people, including myself, had anticipated. (A caveat: We cannot know how much the election spread coronavirus for several days.) Still, election officials said that voter turnout was high, perhaps higher than expected, suggesting that Myanmar citizens were both eager to vote and potentially satisfied enough that they could safely vote. Turnout may well match the high turnout of the 2015 election, despite the pandemic.

Third, despite concerns that the NLD’s approach toward the Rohingya and other ethnic minorities—which led to challenges to the NLD by ethnic minority parties in many regions—it appears highly possible that the party will actually win more seats than in its 2015 landslide. Although official results are not in, a NLD spokesperson told reporters that not only would the NLD gain a majority of seats in the upper and lower house to form a government, but it would surpass its numbers of seats from 2015. Political analyst Yan Myo Thein told Reuters that “early results showed ethnic parties had won some seats in Kayah, Mon, and Shan states, where many people harbor grievances against the central government but the overall picture was of another NLD landslide.” (Some ethnic parties had merged with each other and will pick up seats in parliament and perhaps do even better in state legislatures, but the NLD still appears to have won a huge majority in ethnic minority areas.)

Apparently, the appeal of Suu Kyi and the NLD—as a historic opposition, as a bulwark against military rule, as the only real national party with grassroots outreach across Myanmar—may have been enough for many ethnic minority voters to choose the NLD, despite the failures of the peace process and the rising anger toward the party in some ethnic minority regions. In addition, the NLD seems to have won nearly every seat in areas with majorities of ethnic Burmans, the country’s majority.

If the NLD does indeed win by an even larger margin than in 2015, and the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) does worse—it looks like it is getting crushed and the NLD is taking seats from areas the USDP previously held—the NLD would potentially have the opportunity to follow through on promised reforms that would reduce the power of the armed forces, the dominant institution in Myanmar. This indeed would be a major battle in Myanmar politics after the election, and one that could determine the country’s future.

Joshua Kurlantzick

Republished from Asia Unbound – Council on Foreign Relations

Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect FORSEA’s editorial stance.

Banner Image: Mandalay / Myanmar – September 2020: T-Shirts with the picture of Myanmar political leader (Aung San Suu Kyi). Photo: Robert Bociaga Olk Bon / Shutterstock.com