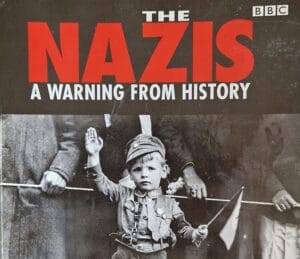

Banner: The entrance to Bremen Station, taken at the height if the Nazi power in 1941. (Source: Laurence Rees’ book).

For those who closely watch the increasingly irrelevant U.S. Congress, you will be aware that Republicans currently propose adding Trump’s face to Mount Rushmore and making his birthday a national holiday, in honor of what they call the Golden Age he is claimed to be introducing. Golden Ages are what all revolutionary leaders claim to be introducing. Virgil claimed this of the rise of Emperor Augustus. Others said this of Nero. Napoleon was believed to be doing this for France. For Mussolini, it was a revived Roman Empire for Italy. For Hitler, it was the Thousand-Year Reich.

The problem with these great men who promise Golden Ages is that, in most cases, they do not deliver. To build a legacy of glory, they need to ruin what came before. Hitler burned the Reichstag and would later comment favorably on the Allied bombing of Berlin, saying they were doing his work for him in preparing for the construction of a glorious new capital, Germania. In Nero’s case, he allegedly sent agents to burn down Rome while he watched from his villa. As his executive power was stymied by the Senate, a destroyed Rome would allow him to rebuild it as he wished, without interference. Napoleon famously depleted his manpower reserves in a futile campaign in Russia and, once dethroned, would later return from Elba to sacrifice another generation of young men in an effort to restore his empire.

Gigantic egos—the kind that propel men like Trump and Elon Musk to positions of power (as Musk has clearly done despite being born into a privileged white family in Apartheid-era South Africa)—leave little room for anything else. Societies, classes, peoples, races, and all other human communities are expendable, just as are the material accomplishments of civilizations and states. What exists before Year Zero, as Pol Pot no doubt believed during the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–1979), is merely the legacy of the past—something to be permanently erased, replaced by something new built on ashes rather than on older foundations. If revolutions eat their children, it is the Caesars of our world who set the table.

Michael Charney, FORSEA Board Member

We do not have many great things to say about the Caesars of (global) human history. Their reigns are not remembered fondly by most but as times of suffering. Only in the aftermath of ruin, death, and loss do populations come to their senses, emerging stronger for having endured hardship—separately, on different sides of an imagined line drawn for the Caesar’s political gain. We try to commemorate the end of wars not for how far they satisfied a ruler’s bloodlust but for the cessation of bloodletting itself—marked by rows of white crosses in Normandy, the rusting barbed wire at Auschwitz, and the piles of human skulls in the rooms of Tuol Sleng. These are lessons not in the good that great men can do, but in the folly of allowing them the power to drag entire populations along with them. A lesson we claim we will learn from, but never do.

In some constitutional systems, checks and balances exist to protect the government and society from the abuse of any one branch that might serve as a power base for a Caesar. It can be an imperfect system—an obstacle to progress, reform, and change. It can be a source of abuse, waste, and fraud. But it is also designed to prevent the rise of a Caesar. Where it blocks reform, it also blocks revolution. Where it hampers the consolidation of one man’s power, it protects the representation of the people. In the words that Dalton Trumbo put into the mouth of Roman Senator Sempronius Gracchus, who resisted the efforts of Marcus Licinius Crassus to seize authoritarian power in Rome: “I’ll take a little republican corruption along with a little republican freedom, but I won’t take the dictatorship of Crassus and no freedom at all.” Historians will remember that beyond the limits of the film, Crassus would lead Roman armies into disaster in Syria, where his forces were surrounded and destroyed, and he himself was beheaded.

The book cover of Laurence Rees’ BAFTA-winning BBC TV Series “The Nazis: A Warning from History”, BBC Worldwide Ltd., 1997

Trumbo was writing from experience. Blacklisted during America’s Second Red Scare in the mid-1950s, he lived through an era when U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, with the cooperation of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, sought to destroy Americans labelled as Leftists—people believed to have infiltrated the government, entertainment industry, and academia. An accusation alone was enough; many lost their jobs based on decisions and laws later ruled unconstitutional, as well as through informal pressures that were later deemed illegal. Ironically, Cold War-era documents have shown that there was indeed Soviet espionage in the U.S. at the time, but the real spies were often missed, while innocent people were targeted. As a result, America emerged more divided. We had nearly burned down our own house—or, rather, sat silently by while someone else did it. Trumbo understood the devastation that weaponizing the government against dissenters could bring, and he warned against it.

Our only safeguard—as a country, and given the U.S.’s global influence, as a world—is when the elected occupants of government branches actively enforce the checks that keep Caesar as no more than a president. It is a sign of health, not sickness, when the Executive Branch does not always get its way. It is a sign of disease when our Congressmen and Senators attempt to honor a president as a Caesar and abandon their duty to defend the Constitution. Democracies die easily.

Hail Caesar!

Mike Charney

Professor, SOAS, University of London