In any history, there are certain events which produce a seismic impact on the course of a country or a people’s future. For the peoples of Myanmar, that event has to be the 19 July 1947 assassination of Aung San (then 32) and half of his pre-independence cabinet of multi-ethnic and multi-faith background.

A quarter century after General Ne Win staged the 1st decisive coup against the civilian government of PM U Nu on 2 March 1962, the military rule had proven economically ruinous, ethnically progressively divisive and politically repressive. Former Brigadier General Aung Gyi, the second in command in Ne Win’s coup regime – the Revolutionary Council Government – broke the taboo regarding Ne Win’s pseudo-socialist military dictatorship with his open letters to his former commander-in-chief. Importantly, the same Aung Gyi also spelled out officially that Rohingyas were equal citizens and an integral ethnic community of the Union of Burma, like all other borderland ethnic communities who saddled the newly drawn-up borders of different nation-states which emerged as the direct result of the dissolution of British Empire post-World War II.

Source: Asia Week published on 8 July 1988 (This appeared 2 days before my departure for the United States to begin my university education at the University of California at Davis.)

Specifically, Aung San and his post-World War II colleagues succeeded in hammering out the twin framework for the nature of the post-colonial political state, namely the federalist power-sharing arrangement, which recognized the right of self-determination of ethnic communities, and an inclusive citizenship framework, which was anchored in both the idea of indigeneity and the status of local residency a decade prior to the end of the pre-World War II British rule in 1942.

Source: The constitutional implications of Myanmar’s peace process | ConstitutionNet

The artist’s depiction of the Panglong Conference, February 1947. The leader of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League Aung San (in the military uniform) was seen here with the host Sao Shwe Thaike of Yawnghwe ruling house (in off-white Shan jacket, on Aung San’s left), and Shan and other ethnic and political representatives at the conference of Hill Peoples and the Bama representatives of the plains) in a southern Shan state town called Panglong, February 1947.

With the benefit of the hindsight of 77 years, I for one trace the origin of Burma’s unfolding internal Balkanization to this vent, albeit without the emergence of new republics or alteration of external boundaries.

Both civilian politicians with huge sway over the dominant ethnic Bama and the 3-generations of military leaders who have instituted and maintained a military dictatorship since 1962 have discarded, in spirit and in deeds, the country’s founding principles of ethnic group equality and inclusivity in granting equal and non-tiered citizenship to all persons, irrespective of race, faith, and creed.

Source: “Rohingyas are equal and full citizens and an ethnic minority integral to the Union of Burma”: Myanmar Military Leadership, July 1961 | Zarni’s Blog (maungzarni.net)

[Also see Myanmar’s Rohingya People: A Documented History, Identity and Presence https://forsea.co/myanmars-rohingya-people/ ]

Consequently, the non-Rohingya public, both the Bama majority and other indigenous public, typically referred to as Taiyintha, or in Sanskrit Malay Bumiputra, that is, children of the soil) sleepwalked, as cheerleaders (and collaborators, in the case of Rakhine Buddhists), into the military-initiated decades-long persecution. My colleague Natalie Brinham (then the pseudonym Alice Cowley) and I sounded alarm over this breach of international law and civilizational norms with our 3-year study, “The slow-burning genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingya” (2014).

Three years on in the fall of 2017, this persecution climaxed into a textbook example of genocide, resulting in the exodus of nearly 1 million Rohingya – and countless deaths and destruction of over 300 villages and neighbourhoods in Northern Rakhine, at the hands of Myanmar Armed Forces, aided and abetted by local anti-Rohingya Rakhine collaborators.

By 2019, the State of Myanmar was hauled before the International Court of Justice, the United Nations’ principal judicial organ, for its alleged breach of the inter-state treaty called the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide. Then in her capacity as Myanmar State Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of the martyred national leader Aung San, represented Myanmar as a state party to the Convention to defend and deny that what she calls, with pride and affection, “my father’s army” had ever perpetrated genocide and dismiss any allegations and evidence of the military’s mass rape against hundreds of women whose identity as ethnic Rohingya she categorically refused to recognize.

In November 2017, I had travelled to Rohingya genocide survivors’ camps and conducted video-recorded in-person interviews with over a dozen Rohingya women who survived or witnessed the rape in Rakhine state across the land and river borders from Bangladesh. I knew the daughter of Aung San, my role model and hero, both in my childhood and to this day, was lying through her teeth.

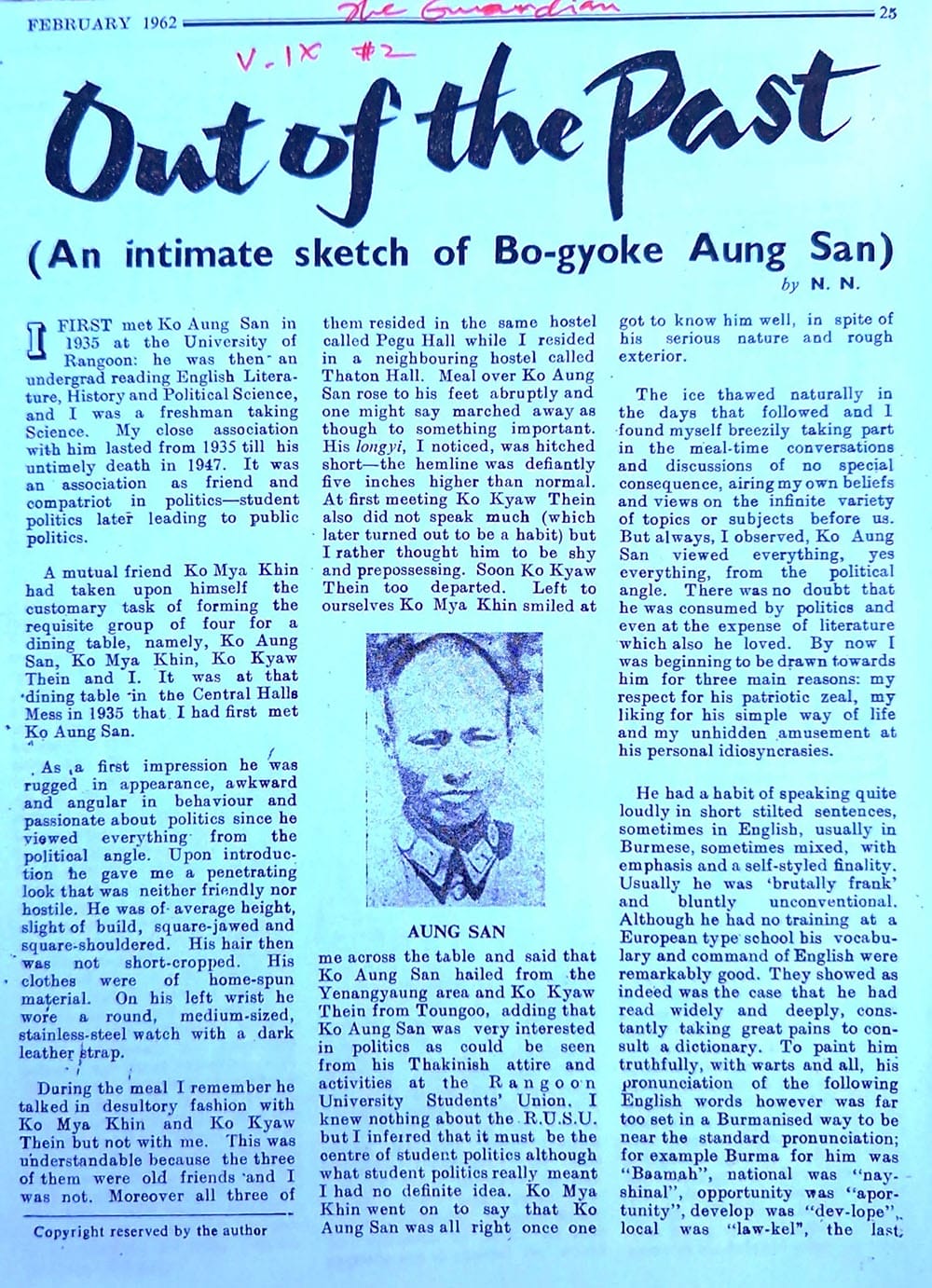

A word about Aung San

Born in the ethnic heartlands of the Dry Zone (or Upper Burma) in 1915 to a small land-owning family, the young student anti-imperialist agitator-cum-Marxist-informed revolutionary leader, was a self-made man who lived his singular dream of liberating the colonized society of multi-ethnic peoples, both those who claimed indigeneity and those who adopted colonial Burma as their home. He drew his inspiration in defining who belonged in the country not from the blood-anchored conception of a Burmese or non-Burmese indigenous person, but from the progressive citizenship definitions of both the USSR and USA. In his widely listened to public addresses, he made his radical post-ethnic/-racial definition of “taiyinthar” or “children of the soil” as anyone who adopted the country, expressed his or her concerns for the collective welfare of all people and contributed to the country’s progress.

In a country where the majority Bama possessed Fascist and authoritarian tendencies, which were publicly pointed out by Thakhin Ba Hein, Aung San’s peer at Rangoon University in the 1930’s and subsequently the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Burma, a small band of Marxist-inpired university-educated revolutionaries, including Aung San, broke free of these psycho-cultural impediments. They attempted to advance the non-racist and non-authoritarian conception of political citizenship – and ethnic group equality among the soon-to-be independent colonial Burma. I learned first-hand about these two remarkable revolutionaries from my great-uncle who was a classmate and friend of both Aung San and Ba Hein. Between the two leaders, who headed the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) and the Communist Party of Burma, Ba Hein died first, a natural death in my old high school in Mandalay, which was converted into a World War time hospital by the occupying Japanese Fascist authorities.

Months later, Aung San and his multiethnic colleagues were gunned down in a successful assassination plot during the mid-morning cabinet meeting. Despite the overwhelming evidence of Britain’s involvement, from multiple credible sources, U Nu, Aung San’s deputy and Vice President of the AFPFL, and his colleagues attempted to conceal the instrumental role the British played in eliminating the most influential Burmese nationalist politician, who publicly talked about the intention of his post-colonial government to nationalize resource extractive industries (such as oil and mining) as well as other strategic economic sectors.

Watch the BBC Two documentary produced and directed by Rob Lemkin, my old friend and neighbour in East Oxford. Who Really Killed Aung San? ( 1997 ) By BBC2 Television (youtube.com)

In terms of Aung San’s national political program, he succeeded in persuading different ideological and ethnic representatives – who represented socialist leaning new ethnic masses, the centuries-old feudal ruling houses from the hill areas of Western, Northern and Eastern Burma and tradition-bound Bama nationalists with feudal outlook – to work together voluntarily and forge the former colony as a federalist democracy, an unprecedented historical vision.

The principal representative of the Bama or Burmese from the plains Aung San offered the gathered representatives of Shan states (29 in total) and other hill regions ethnic group equality as the founding principle for forging a new voluntarily federated Union of Burma. The British colonial authorities who returned to Burma after the defeat of Japanese Fascist occupational forces in the spring of 1945 sought to keep the resource rich and strategic hill regions under the control. Aung San addressed a group of leaders of the hill peoples who were gathered in Taunggyi, Shan Hills, on 8 February 1947, stating, “we should win independence from Britain as a united people. Independence from Britain doesn’t mean you switch from being ‘Britain’s slaves’ to being the slaves of the Burmese’”.

Source: Bogyoke or General Aung San’s Collected Speeches (1945-1947), Sarpei Beikman Press (Government Printing House), Rangoon, 1971.

The late Maha Devi (or chief queen) Sao Naw Hkan of the ruling house of Yaunghwe, Southern Shan state wrote to her American friend and the resident economic adviser to U Nu’s Government named Louis Walinsky, that “it was Aung San who in fact offered to include the right of secession or self-determination in Panglong”, (the country’s “founding treaty” among different ethnic groups albeit Rakhine and Karens were not party to it).”

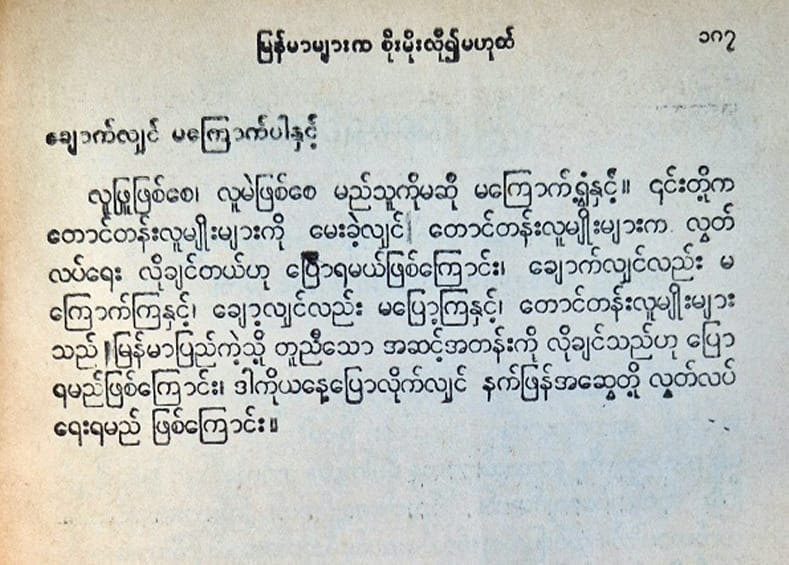

The late Louis Walinsky at home in Washington, DC with the painting of his life-long friend the late PM U Nu of Burma. (Circa. 2000). Uncle Lou, as some of us called him with great affection for his unwavering intellectual, political and financial support for anti-dictatorship movements, served as the Chief Economic Adviser in residence (in Rangoon) to the Union of Burma Government from 1953-58. He was very well-connected in Washington Belt Way politics, which he used to assist the Burmese dissidents in exile. His son Adam was the speech-writer and campaigner manager for Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign until RFK was assassinated. (Photo by Zarni).

Apparently, Aung San wanted to convince the ethnic representatives who gathered at a small hill station town of Panglong hosted by her husband, Sao Shwe Thaike, that he meant business when he offered ethnic group equality.

I read the letter when I was sorting out some of the archivable materials for the Louis Walinsky Collection for Cornell University after Lou’s death in Washington, DC.

(She was the mother of Harn Yawnghwe who directs the Euro-Burma office and advocates for peaceful political negotiation in the federalist spirit of Panglong as a way to end the 70-years of civil war raging with fluctuating degrees of ferocity.)

The two Yawnghwe brothers, the late Eugene (4th from the left, with dark sun glasses) and Harn (second from the right with glasses) standing next to the author (far right), with other dissidents in exile from Burma), Harpers Ferry, Western Virginia, USA (after the completion of a 2-days’ retreat of the pro-federal democracy exiles including the leaders and officials of the now defunct National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (in exile)who supported Aung San Suu Kyi, then under house arrest, February, 1999). Photo in Zarni’s possession.

But Aung San’s federalist and democratic vision has had one big problem.

Nether his successor, the late PM U Nu, nor his own surviving daughter Aung San Suu Kyi shared this commitment to ethnic group equality.

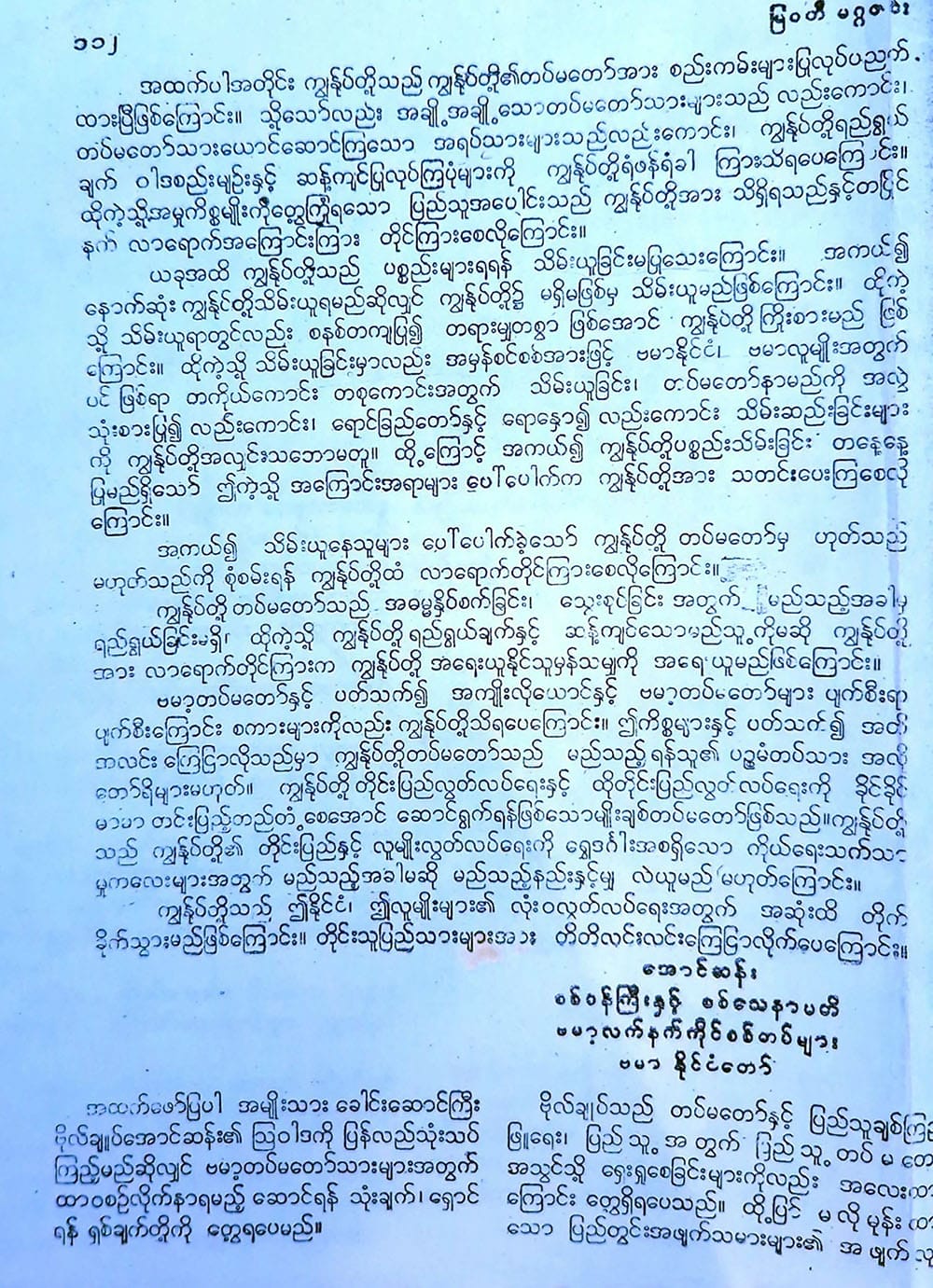

In a type-written copy of the Burmese language letter – in my possession – written to his anti-military dictatorship armed comrades dated 2 March 1973 (see the Burmese language letter in insert) , when he was the figurehead, U Nu confessed that from the day he became the post-Aung San leader of independent Union of Burma he was opposed to the right of self-determination of any ethnic group, in direct breach of both the spirit and letter of the Union of Burma’s founding treaty of Panglong.

Source: The author’s collection. A copy of this authenticated letter by the ousted PM Nu was gifted to me by the Colorado-based Burmese academic and exile, the retired Professor Kyaw Win, who was a close friend and editor of Nu’s autobiography Saturday’s Son.

The 1947 Constitution of the Union of Burma, completed under Nu’s pre-independence leadership and after Aung San’s assassination in 1947, was “federal only in name, but unitary in substance.” The late Chan Tun, the Cambridge-trained barrister and Aung San’s legal adviser on the Constitution Drafting Committee, admitted this sordid fact to the late Edward Law-Yone, the chief editor of the then influential English daily, The Nation, in the 1950’s when the discontent and strife over the unequal ethnic group relations were beginning to surface.

As a matter of fact, U Nu’s refusal to honour this group equality principle fractured the emerging armed resistance coalition of ethnic Bama, Mon and Karen movements with the common aim of ending General Ne Win’s dictatorship. General Ne Win ousted the PM U Nu in 1962, and jailed him for 5 years, after which Nu left the country and joined the armed resistance movement established along the Thai-Burmese borders by the likes of Law Yone and other liberal democrats.

Likewise, despite the initial embrace and popular support among non-Bama or -Burmese ethnic communities – which make up 30-40 percent of the country’s total population – Aung San Suu Kyi proved herself to be a Bama and Buddhist nationalist, who treated representatives of other non-Bama ethnic communities – and religious minorities – with stomach-turning condescension, barely concealed contempt and apparent ethnic chauvinism.

Today Myanmar’s plunge into the ferocious civil war is accelerating in various ethnic regions – from the coastal Rakhine and hilly Chin states on the western frontiers to Northern Myanmar’s Kachin highlands, Shan plateau, Karenni, Karen and Mon regions along the Sino- and Thai-Burmese border regions. The public is now waking up to the ugly reality: the territorial gains by the anti-dictatorship resistance organizations vis-à-vis the genocidal Myanmar national military do not signify a new, progressive and emancipatory political future for either the locals under the Arakan Army, the Kokang (ethnic Chinese) armed group (Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army) , the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the United Wa State Army, and so on, or the country at large. On the contrary, the intra-minority group rifts and tensions are brewing as the military victorious “ethnic resistance organizations” are promoting their respective strains of ethnic supremacy, whatever their name, with the exception of the Karen National Union and the Karenni National Progress Party.

Absent any inclusive, post-ethnic political framework that guarantees group equality (or federalist arrangement) among ethnic communities whose presence is now interspersed across different mono-ethnically named regions, commitment to universal human rights and democratic principles, Myanmar is heading towards a hybrid between dismembered Syria and the ethnically poisonous post-Yugoslavian states.

Of course, unlike the disintegration of Tito’s Yugoslavia which resulted in new republics allied with different external geopolitical powers such as Russia, USA, EU and, (to a lesser extent, China), the late Aung San’s Union of Myanmar will remain a permanently divided society of overly ethnicised, racist populations within its external boundaries primed for strategic exploitation via their local ethnic proxies, by different external actors such as China, India, Thailand, and USA.

You can kiss goodbye to a federalist democracy, with human rights.

“The group MNDAA that has taken over the key town in Northern Shan State, Lashio, is the Mandarin-speaking local Han Chinese group although the area is historically and ethnically predominantly Shan. The MNDAA is establishing a local administration based on Chinese racial identity and Mandarin language in an area that is ethnically and linguistically diverse. Their methods of law and order mirror that of Chinese Communist Party, including public executions of any offenders. This Han Chinese/Kokant groups have for decades been known to be a crucial economic actor in the heroine global trade, money laundering and more recently running cyberscam centres, all by the approval with Myanmar’s national armed forces, which in turn pitted the commercially driven Kokant militia against ethnic Shan federalist armed resistance organizations.”

Backgrounder

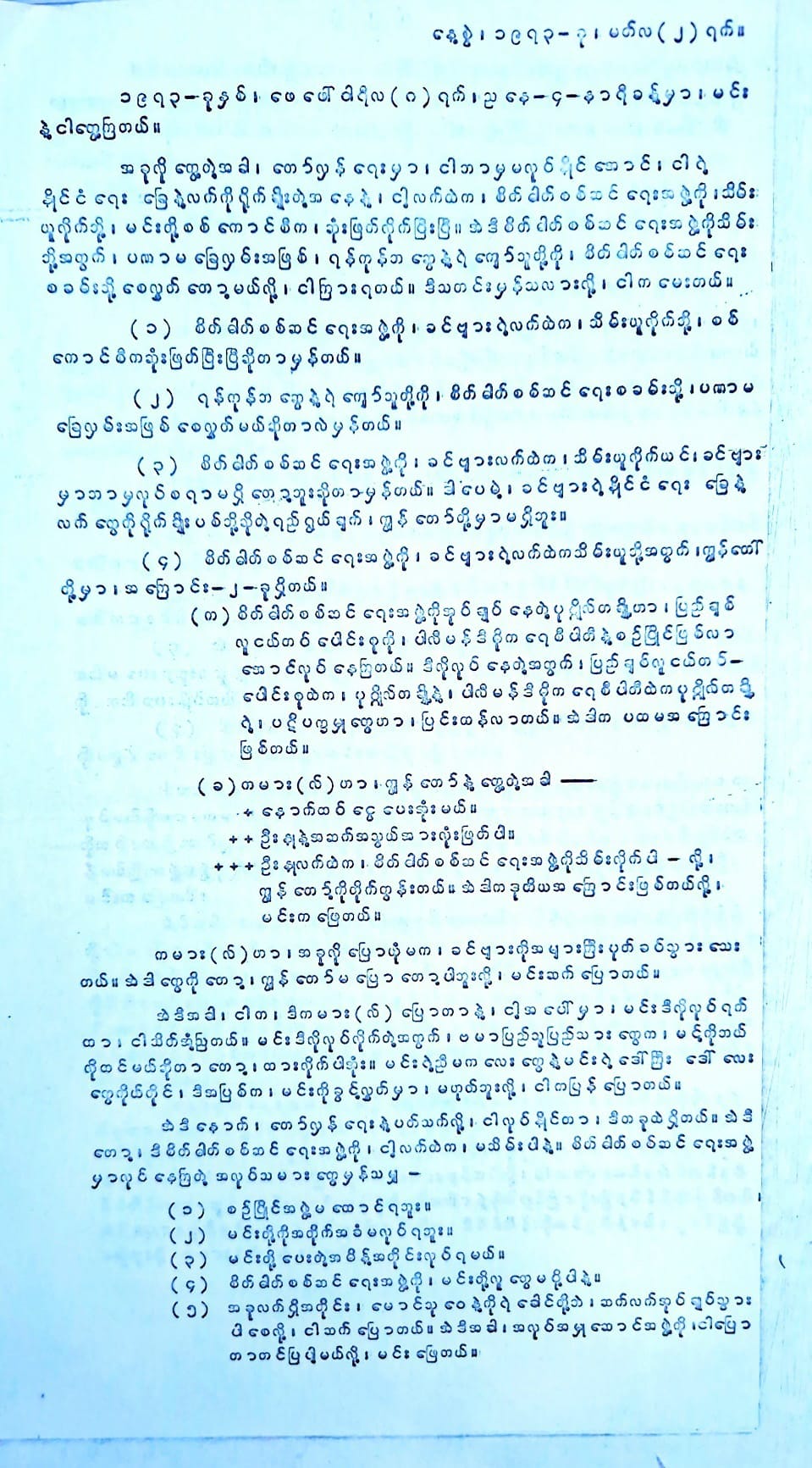

Aung San’s Address to the 4th meeting of the national leaders of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League, the emerging ruling coalition after the defeat of the Fascist Japan in the Burma theatre, August 1945. He spelled out the 4-piller anti-Fascist program for post-colonial Burma, which rests on democracy and self-determination of all ethnic groups.

Aung San on the strict separation of religion and politics.

Aung San’s anti-ethno-supremacy views and pro-democratic values including the parliamentary/civilian control of the armed forces.

Aung San on the code of conduct and ethical principles governing the behaviour of the Burmese military personnel.

The following article written by Chit Hlaing, the chief-ideologue of General Ne Win’s Burma Socialist Programme Party, the political wing of the Revolutionary Council junta, advocated the abolition of Ethnic Supremacy of the dominant Bama or Burmese group. It was dated February 1967 and published by the Ministry of Defence Psychological Warfare Department publication Myawaddy, Rangoon. The civilians and military officers who genuinely subscribed to the socialist idealism and principles sought to transcend ethno-centric and racist ideas and values prevalent in the Burmese society. But progressively, the military leaders pushed out the civilians and soldiers who had intellectual integrity and political independence as it moved to embrace racism and ethno-nationalism.

Maung Zarni

Banner: Colonel Aung San and Daw Khin Kyi after their marriage in 1942. Wikipedia Commons