The first 100 days of the Trump Administration have seen dramatic changes in the Executive Branch’s approach to governance, how the country conducts business, and its relationship with education—both at the K–12 and university levels. While it is clear that the Executive Branch supports increasing authoritarian powers—evidenced by executive orders issued at the expense of conventional constitutional processes and by pushing the limits of executive authority to the point of challenging the legitimacy of the courts—this strategy remains unclear, largely due to the double-talk of many government actors enabling the White House. Tactically, this has been referred to as “filling the zone,” but the actual strategy behind it is opaque.

What is clear is that the main overt promises made by the administration during the 2024 election appear to be low priorities. Whether ending the war in Ukraine in a single day (as promised), lowering consumer goods prices (the opposite has occurred), or making America great again (which is demonstrably failing if measured by international trade and diplomatic relationships), these pledges have been sidelined. Some insiders have profited—selling commemorative coins or capitalising on the dramatic stock market dip—while others, such as South African–born white billionaire Elon Musk, have lost money, due mainly to negative domestic and international reactions to his public behaviour in support of the White House.

The administration has been most successful in ending Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programmes in schools and universities, alienating majority-Black governments such as South Africa’s, blaming a series of air accidents on “diversity hires,” and removing (until protests forced reinstatement) photographs of famous African Americans from the Pentagon’s walls. It has also embarked on deportations of Latin American immigrants—many of whom are not undocumented. Meanwhile, the White House has expressed serious interest in annexing majority-white Canada, with no comparable ambitions directed toward Mexico, the Dominican Republic, the Bahamas, Jamaica, or other majority non-white societies close to America’s shores.

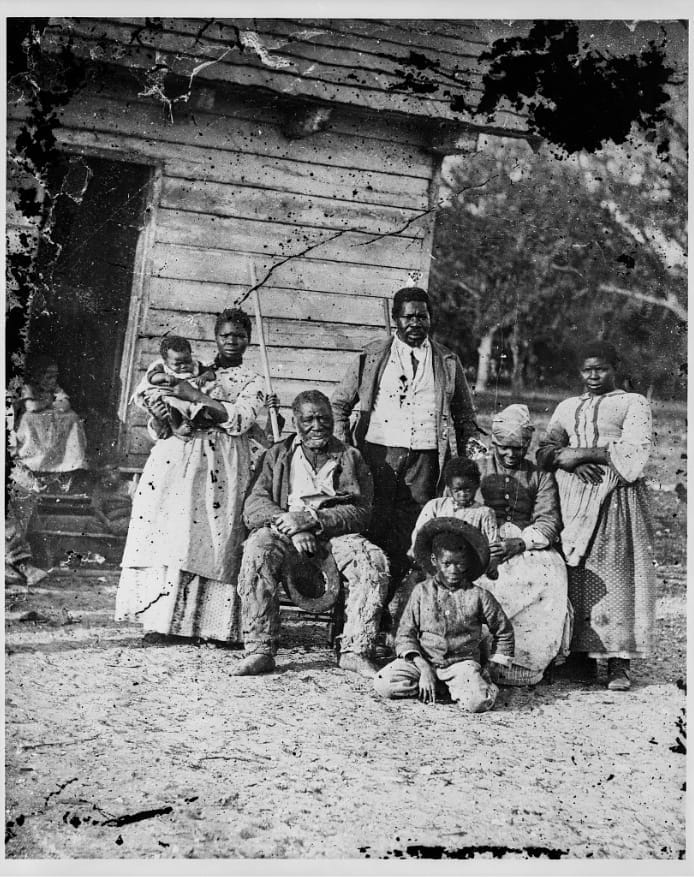

1862. Five generations on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina. US Library of Congress.

Support for Israel comes as no surprise, given longstanding American foreign policy. Like the US (as well as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and apartheid-era South Africa), Israel is a white settler state. Its colonisation of the West Bank—and now, perhaps, a decimated Gaza—is more recent than America’s own settler history, but many American presidents have recognised in Israel a kindred spirit. Much of Critical Race Theory (CRT) was developed to explain structural racism and its negative effects on racial minorities in the United States, but it can also help explain the fears and priorities of other white settler states. There is a fear for the survival of the state and society, for the maintenance of white privilege, and for the protection of white power. This is easily maintained in majority-white democracies. For example, apartheid South Africa created ten bogus African sub-states (Bantustans) to technically render the white population the majority over the remaining 87% of the country’s land. Australia maintained a “White Australia” policy for decades, imprisoned undocumented immigrants on offshore islands, and more recently saw its white electorate reject a national-level advisory Aboriginal Council. The US delayed ending Black slavery until after the Civil War, committed genocide against Native Americans, who were not US citizens until 1924 and did not have the right to vote until 1948, and saw violent opposition to African American civil rights continue into the 1970s. Today, it is moving towards mass deportation of Latin American migrants, blocking further entry, and restricting the ability to work to only those fully competent in English—despite the US having no official language.

Mainstream media, blinded by structural racism, has shown only modest concern about the dismantling of DEI. Even sympathetic critics of Trump have not reacted strongly to attacks on “wokeism” by administration officials. In terms of optics, the racial representation of the 24-member cabinet is overwhelmingly white. Marco Rubio is a Cuban American of white European heritage. The only non-white members are Mexican-American Secretary of Labour Lori Michelle Chavez-DeRemer and Black American Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Eric Scott Turner. A story by The Washington Post highlighting this surreal racial makeup passed in mid-February with little public debate.

Today, over 40 percent of the US population is non-white. As early as 2014, the majority of students in American schools were non-white. The US not only had its first Black president from 2009 to 2017, but nearly elected a second Black president in the 2024 election.

Is the timing of these developments and the policies enacted by Trump in the past three months merely a coincidence—or were they triggers? Is the strategy behind the administration’s policies an effort to “circle the wagons”? PBS News noted in April the irony of the Trump administration shutting down refugee programmes, only to offer refugee status to white South Africans seeking to resettle in the US. Arguably, this is no irony. Settler populations tend to protect their own. As Latin Americans are pushed back south of the border and, if Trump has his way, Canada’s white majority is absorbed into America’s racial demographic balance, Trump-adviser Elon Musk has publicly stated he dreams of freer movement—of labour and trade—between Europe and the US. Why the same free flow is not extended to other regions remains unclear.

While the US government domestically circles the wagons, mobilises the cavalry, and urges settlers to take refuge within a metaphorical Fort Apache 2025, it does so internationally as well. For some Americans, soft power and global influence mean little if they do not serve a white-dominated national identity. If America is no longer for the white settler society, then its democracy, civil rights, and global aid efforts begin to seem hollow. In the end—despite America’s reputation for being ruled by the dollar—it has now shown it believes blood (race) is even more important than money.

Michael Charney is a full professor at SOAS, the University of London, in the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy (School of Interdisciplinary Studies) and the School of History, Religions, and Philosophies, where he teaches global security, strategic studies, and Asian military history.

Michael W. Charney

SOAS, the University of London

Banner: American Progress (John Gast painting, 1872). It shows Manifest Destiny, the belief in westward expansion of the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. It was widely distributed as an engraving called “Spirit of the Frontier”. Wikipedia Commons