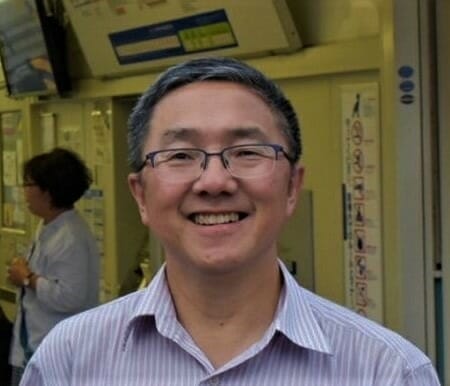

On 24 November, FORSEA kicked off its inaugural YouTube series Dialogue of Democratic Movements Across Southeast Asia with an extremely erudite and prolific Thai scholar Thongchai Winichakul.

Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Thongchai is no ordinary academic.

He was one of the most prominent student leaders of the Maoist-inspired democratic uprising of 1976, which ended with a brutal massacre of nearly 4 dozen student activists by the Thai police and pro-monarch thugs. Post-his revolutionary activism, Thongchai remade himself as a radical historian of Thailand: his academic pursuit has been far more successful than his political activism. In the career than spans more than 3 decades Thongchai has reached the pinnacle of academic careers: a recipient of the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Award for 1994, President of the Association of Southeast Asian Studies 2013/14 and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected in 2003). Thongchai’s Siam Rapped (1994) won the 1995 Harry Benda Prize designated for the best study on Southeast Asia from the Association of Asian Studies and is widely considered a classic on the construction of a nation and national identity by many Southeast Asianists. His latest monograph has just been published by the University of Hawaii Press, entitled “Moments of Silence: the Unforgetting of the October 6, 1976, Massacre in Bangkok,” a brutal event of mass-murder of students including some of his closest comrades which he himself witnessed up-close.

He was one of the most prominent student leaders of the Maoist-inspired democratic uprising of 1976, which ended with a brutal massacre of nearly 4 dozen student activists by the Thai police and pro-monarch thugs. Post-his revolutionary activism, Thongchai remade himself as a radical historian of Thailand: his academic pursuit has been far more successful than his political activism. In the career than spans more than 3 decades Thongchai has reached the pinnacle of academic careers: a recipient of the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Award for 1994, President of the Association of Southeast Asian Studies 2013/14 and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected in 2003). Thongchai’s Siam Rapped (1994) won the 1995 Harry Benda Prize designated for the best study on Southeast Asia from the Association of Asian Studies and is widely considered a classic on the construction of a nation and national identity by many Southeast Asianists. His latest monograph has just been published by the University of Hawaii Press, entitled “Moments of Silence: the Unforgetting of the October 6, 1976, Massacre in Bangkok,” a brutal event of mass-murder of students including some of his closest comrades which he himself witnessed up-close.

As the dialogue host, I made an unforgivable sin of miscalculating the time difference, and had made my distinguished guest wait for nearly 40 minutes! We discussed re-scheduling the live event for the following day. But at my urging Thongchai agreed to proceed though we were practically one hour behind the advertised schedule.

Once our initial anxieties – that the audience would have left – faded the subject matter of democratic resistance in Thailand over the last 3 generations really got us going. Our dialogue went on for almost nearly 2 hours, and we covered several thematic issues including the intellectual applicability of Siam Mapped, his critically acclaimed study of the invention of Thailand as a “modern” monarchical-military state, beyond Thailand, his deeply personal attempt to honour his fellow student activists from Thammasat University uprisings who were brutally tortured and murdered on 6 October 1976 and to hold to account the palace and the Thai society alike, and his attempt to continue to mock the feudal ideas.

Thongchai gave a historian’s overview of various waves of reforms and resistance chronologically, going beyond personalities while presenting the impersonal factors such as the Cold War and the institutional self-interests of the country’s military in shaping the contours of Thai political and cultural developments.

Against the backdrop of the current framing of protests as “unprecedented” in the way they publicly and frontally criticise the Thai monarchy and the monarch himself, Thongchai reminds us that it was only 2 or 3 generations ago that the public in Thai kingdom were able to openly talk the monarchy-monarch, critically or not.

It was the Cold War “Communist Containment policies” of the United States that had tilted the kingdom’s power equations in favour of the monarchy-monarch whose wings were clipped by the Thai reformers in the 1930’s 1940’s who wanted to remake the Thai monarchy a constitutional one, in the mould of the British or Japanese monarchy.

Washington used the Thai monarchy and its legitimizing political ideology, namely Buddhism, as the propaganda firewall against the advent of Communism, Socialism and Maoism. Thongchai identified himself as a “socialist” and “Maoist-inspired student activist” in those days during which Southeast Asian university campuses and rural communities were attracted to egalitarianism supposedly enshrined in the political programs of USSR and Maoist China.

Today Thongchai however, welcomes as a healthy trend a discernible absence of vanguardist leaders and organizations who would articulate a utopian vision for the political public above all activists on the front line.

Thongchai highlighted the instrumental role which Thai secondary school students – many of whom young women and girls who found themselves at the bottom of the patriarchal Thai society and political system – are playing, and their savvy use of the new social media platforms and smart phones. In his view, the protesters are – thanks to the new information technologies able to break free themselves of the monarch-military state’s monopoly control of information, or over “the correct way” in which Thai students are supposed to think – about themselves, about the ruling institutions, about their extremely conservative “Buddhist” culture and so on.

On his part, Thongchai no longer adheres to a systematic formulation of ideological vision, and is content to view the achievable and less violent goals of revolutionary push for change as the emergence of a new progressive consciousness among students, youth, women and those on the margins of society and the method or space whereby the plurality of competing ideas can comingle without violence or disruptions.

Importantly, he is acutely concerned about and accordingly rejects what he views, quite rightly, as the mis-portrayal of today’s ongoing political movement in Bangkok and many other parts of the country as “republican”.

Older and apparently wiser, Thongchai with a self-confessed tendency to mock feudalists and their institution, said, with a chuckle, “I don’t mind the monarchy – I should say, “palace” – any more. We should all just ignore it (and get on with our lives)”.

Given how bloody and violent the process of republicanizing kingdoms, Thongchai does seem to have a point: if the protesters’ attempts at re-forming the palace along the British and Japanese models of constitutional monarchies suceed – where the royalty are not permitted to interfere in the genuine parliamentary government for and by the People, Thailand might very well avoid the cycle of constitutions, military coups, street protests and violent crackdowns.

Maung Zarni

Thailand 29/10/2020: Anti-government protesters in front of Silom Complex Bangkok. Photo Sumeth anu / Shutterstock.com