Recently, I came across a poster promoting an upcoming conference panel featuring prominent Malaysians who advocate for refugee rights. Such configurations in Malaysia’s public sphere have become a norm in recent years despite the increasingly violent crackdowns by the Malaysian government against refugees and migrant workers (documented or undocumented). The panel itself does not feature a person from the refugee community, but what caught my interest was the title of the panel;

“Amplifying Silent Voices of Minority Communities”

“The piece illustrates power relationships, borders, mortality, physical confrontations and human vulnerability.” – RefugiArte: The Refugee Crisis illustrated by Latin American artists (UNHCR).

Silent voices

I can’t help but think that the phrase “silent voices” is an oxymoron. That perhaps it can be potentially harmful because it operates on the basis that minority communities cannot be heard on their own terms. Instead, the community requires an outsider to wield their power to ensure the “silent voices” can be heard.

Ajnabi اجنبی: The outsider, the foreigner, the stranger, the alien

For me, voices are never silent. Voices are produced by sound which means they can be heard. The question is whether we choose to hear and acknowledge them, or attempt to silence them.

It is at this juncture where the Arabic word, ajnabi seems to capture relationships of mutual aid with underlying hostilities. By no means I am accusing passionate activists or refugees of committing anything insidious. I just find myself wondering if we, as a collective of workers for social justice, ever critically interrogate our approaches to the representation of minority communities in public advocacy.

Almost three years ago, I made the mistake of putting together a public forum about the role of Orang Asli communities in mitigating climate change. I had invited a white British male anthrozoologist and Malaysian Chinese-British male environmental scientist to be moderated by a Malay female climate action activist.

Initially, I naively believed that I was doing something good by gathering two academics to authoritatively speak on their research based on interactions with indigenous peoples in the forest frontiers of Peninsula Malaysia. Although the session was extremely informative and insightful for city-dwellers who are eager to understand these issues, there remained a glaring absence of Orang Asli speaking for themselves as front-liners in the battle with climate change and neoliberalism.

Clearly, I was way out of my depth to have put this together. I didn’t consider how I was causing harm. I actively and bigotedly undermined and erased the existing work of indigenous activists and scholars at the forefront of promoting indigenous knowledge to improve climate change policies in Malaysia.

I often look back at this episode feeling ashamed. Nonetheless, it taught me a valuable lesson along very practical terms about how our knowledge as outsiders needs to be questioned and interrogated to uncover state-sponsored narratives of race, identity, belonging and empowerment alongside our positions of privilege.

“Can the subaltern speak?”, postcolonial theorist Gayathri Spivak asked in 1988

Today, I insist that the subaltern has and always will speak but that we are often too quick to assume that they cannot, and need us to “give voice”.

However, as soon as I opened myself to being more self-aware about my levels of privilege, my identity and listening to members of the community- it is clear to me that this idea of “giving” for “silent voices” to be heard is just a myth. Yet, it continues to be perpetuated by many of us who want to occupy space so that we can comfortably position ourselves as leaders in the movement for social justice.

If we keep thinking of ourselves as the sole arbiter of amplifying “silent voices”, it suggests that we are acting based on the assumption that there is not a single person with the capacity, courage and knowledge to speak on behalf of their community. Certainly, we must know that this is not true. After all, some of us have worked together with numerous activists and leaders that exist within “vulnerable communities”. It is the only means we have come to be aware of their grievances. They would also be much more authoritative than we ever would because we do not inherit their lived experiences and intergenerational knowledge, accompanied by their traumas.

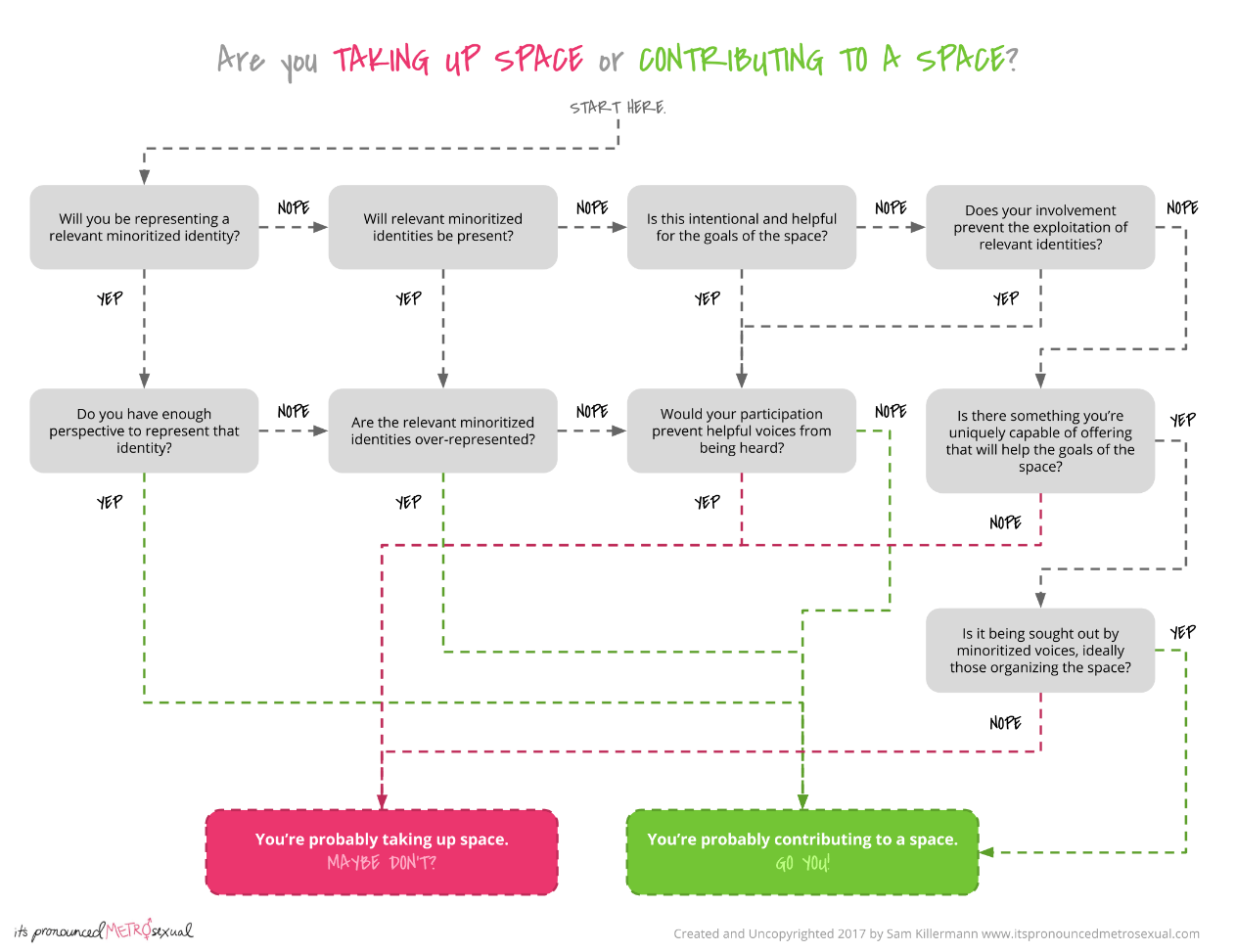

A useful guide to help activists understand if we are “taking up space” instead of “contributing to a space”. Source: Sam Killerman (2017), It’s Pronounced Metrosexual.

Alternatively, when we say we want to amplify voices that are being silenced, I believe this is a lot more intellectually honest and conscious of the reality that state-sponsored, societal and cultural mechanisms of violence try to intimidate these communities into silence on a daily basis. How does assuming the voices of “silent” challenge and attempt to dismantle these structural issues?

Ajnabi, when you say you need to “give” for “silent voices” to be heard, chances are you are not admitting to yourself that you desire to control a narrative of a community that you do not belong to or identify with.

Resultantly, we cannot face the uncomfortable truths of injustices and truly put ourselves on the line to confront the status quo. How can we call ourselves genuine allies if we do not try to do better? We may just be complicit with silencing groups that are banished to the margins, and not part of the solution.

We will not always be right but we have the power to learn and grow. I hope you choose to reconsider how you may express and act on your allyship.

Netusha NRN

Netusha Naidu is a FORSEA Board Member

Banner image: Antonio Gramsci, who coined the term subaltern to explain the socio-economic status of “the native” in an imperial colony. Wikipedia Commons