I. Protest

In the afternoon of January 16, 2020, dozens of Rohingya men from the Burmese Rohingya Association of Japan staged a protest in front of the MOFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) of Japan in Kasumigaseki to convey their urgent message. They carried placards saying:

- Stand with the Oppressed,1

- Call us Rohingya,2

- Stop calling us Bengali,

- Stop Supporting Genocidal Army and the Burmese Government,

- Take strong action on the Burmese Genocide of the Rohingya, etc..

While Japan has accepted these Muslims from Myanmar and Japan has been a place to heal their wounds, they have been deeply disappointed at the excessively close relationship between the Burmese government/military and Japan. The United Nations has recognized the Rohingya as the most persecuted peoples of the world. To see where the MOFA stands on this issue, it is sufficient to ask a few such simple questions as: “Are they Rohingya?” “Is there a Genocide in Rakhine State?” “Has Japan ever tried to stop the persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar?”

The bureaucrats working in the buildings of the MOFA are people who have survived numerous competitions since their youth, and are regarded as elites. The efforts of these elites graduating from prestigious universities, studying hard for successive exams, should be commended, but it is a well-known fact that the level of higher education of children is highly correlated with the income level of their parents. In the MOFA, they analyze international situation, present possible options to the Cabinet, brief members and the Cabinet, or write answers to questions to be asked in the Parliament or write both questions and answers in the Parliament.

However, their image as people with outstanding abilities does not tell the whole truth. Their ability to gather information is undoubtedly one of the lowest among developed countries after 70 years of decline since the end of World War II. In a culture where there is a strong tendency to view higher education just as a labeling of human ability in the first place, the meaning of education after entering university tends to be neglected in Japan. Moreover, although there are no statistics, it can probably be said that the educational attainment of Japanese bureaucrats after entering university is one of the lowest among the developed countries of the world. Some foreign equivalent occupations have Ph.D.s, but it is difficult to find a comparable advanced educational background in the MOFA of Japan. It may also reflect the difference between stress on focused research to produce new strategy and stress on collective and practical work in a group to raise organizational men.

It is rare for people to join the MOFA from other organizations. In the United States, it is common for government officials to be replaced by new teams due to changes at the top, but Japan’s MOFA maintains a closed society and dislikes liquidity, like a fish raising its children in its mouth. After nearly 30 years of overwork the bureaucrats finally begin to find personal gain in their work. If you want to spend the most time as a bureaucrat, your peak normally comes in your late 50s, and someone in the cohort is selected to become the highest-ranking position, which is the undersecretary of the ministry. Those who could not get equivalent posts leave the ministry.

The prospect of this re-employment period is a turning point in their lives that has been scheduled since the beginning of their careers. Even if they are fortunate enough to reach the top of their ministry, there comes a time when they will retire to be rehired as advisors, auditors, etc. by large corporations. This will be repeated several times every few years for the rest of their lives, and at each turning point they will receive a substantial severance pay that exceeds that of employees of other professions. Their new work during this period is rather nominal. The usefulness of these former bureaucrats in this recycle system of human resources is that their companies maintain good existing relationships with the branches of the Japanese government or with foreign governments, or develop new business connections. The Japanese society that makes bureaucrats ex-bureaucrats relatively early and recycles them in the private sector as talents with excellent or valuable experience, offers a scheme to build a broad network between the state and influential industries.

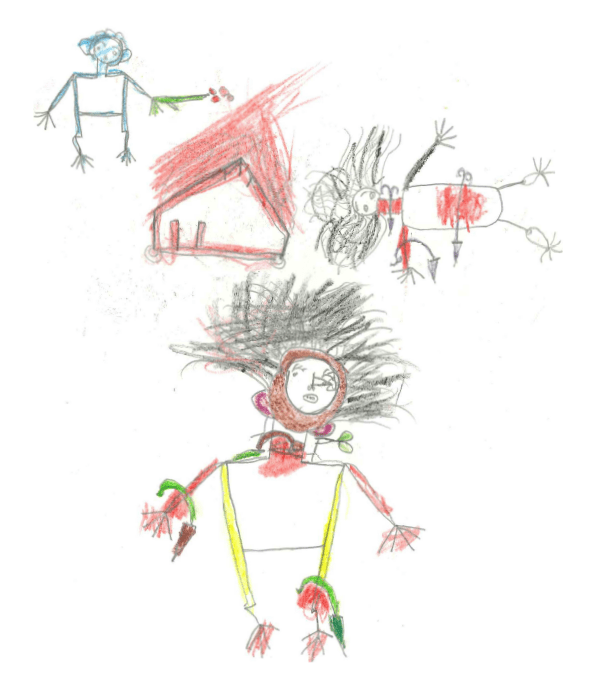

The life cycle of the foreign affairs bureaucracy in the MOFA building, which has steadily built up to the present and is predictable in its future, in its development, in its ending, and in its decision-making process, contrasts with the instability, the catastrophe, and the poor visibility of the lives of the Rohingya who are speaking out in front of the MOFA. Rohingya children have never seen crayons nor drawing paper. When future bureaucrats in Japan were commonly referred to politely as Mr. X, Ms. Y, etc. in schools, Rohingya children were referred to by their teachers only as “kalar,” a derogatory term deliberately chosen by Buddhists in Myanmar for the Rohingya.

Later, when the children who will be future Japanese bureaucrats begin to attend night schools to prepare for exams, the Rohingya do not have such special facilities. By the time the future bureaucrats enter high schools, the Rohingya will not be able to cross the township boundaries of Rakhine State and go to high school. When future Japanese bureaucrats begin to study law and economics at universities, the Rohingya will have to abandon higher education, and even if they are lucky enough to be allowed to go to college, they cannot decide on their specialization. By the time the Japanese bureaucrats had passed civil service exams and started working, the Rohingya were no longer recognized as citizens in Burma, even if their father and grandfather were Burmese nationals who worked for the government.

In Japan, there are cases where a child can realize a wish that the parents could not realize. In the case of the Rohingya in Rakhine State, what the parents were able to realize can no longer be realized by their children. The Japanese bureaucrats serve the powerful no matter who they are,, but the people in power do not change drastically, and the bureaucracy does not expect to be forced to make a major change in policy. Their future is promised and predictable. This stable passage of time becomes the standard time of the world they envision. On the other hand, the Rohingya have already been in a tunnel of long, unpredictable fall into darkness since the birth of their parents, and many died without knowing anything but the nightmare. Some believe that the nightmare they live in is the whole world. Although they seek political change and often fight with other groups against common enemies, they are normally isolated as a group in Burmese society and in the world.

The Rohingyas now standing before the MOFA were born in Rakhine State, many of whom previously supported the National League for Democracy (NLD) and Aung San Suu Kyi, and joined hands with the Burmese Buddhists. But after the so-called 8888 movement symbolized by the general strike of August 8, 1988, was crushed by the junta, participants in the early democracy movement fled, and the Rohingya and the Burmese Buddhist participants began to split.

For many Japanese bureaucrats, the first plane trip may have been a family trip, but for many Rohingya who stood in front of the Foreign Office in protest, the first plane was a means of transportation required to flee to Japan in an illegal way: for example, flying to Narita airport of Japan with a fake passport and being sent from Narita’s immigration office to the “Eastern Japan Immigration Center” in Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture immediately after arrival. They spend a long time until the Japanese government allows them to stay in Japan.

With the help of some devoted Japanese lawyers, politicians, etc., they finally get a certain degree of freedom, but depending on the success of their application, their eligibility for stay varies; some are recognized as refugees and granted permanent residence, some choose naturalization to Japan. Others are denied their requests, released and allowed to apply again. Until the next decision is made, they may remain in Japan. If they are not allowed permanent residence, they will not be able to purchase Japan health insurance.

Many of these Rohingya men are in Japan away from their former homeland and engage in manual labor. Although their lives in Japan are fragile, the lives of their families, relatives and friends in Rakhine State and Bangladesh are incomparably more precarious and vulnerable to raids, arson, looting, disease, etc. The Rohingya in Japan know Rakine’s information almost instantly through the internet and telephone.

People do not live on bread alone, but they cannot live without bread, and many of the countries that send bread to the Rohingya in the refugee camps in Bangladesh, including Japan, are countries that are politically close to the state of Myanmar and looked the other way when Myanmar was chopping them and burning their houses.

The latest wave of attacks on the Rohingya in Myanmar occurred in October 2016 and August 2017, leading to a rather mysterious mass exodus of what Myanmar calls the “Bengali” soon after the military’s “clearance operation” against the “terrorists”, according to Myanmar’s explanation.

Between the NLD government and the military, there was hardly disagreement about what was happening. This period put an end to the Rohingya’s last hope for Aung San Suu Kyi. Both the NLD and the military took the position that there was nothing wrong with the state and that this was a counter-terrorist operation, but after some of the massacres had been exposed by the Reuters reporters, it was difficult for Myanmar to deny the inconvenient truth completely, and then the UN Fact-Finding Commission issued a report. Furthermore, Myanmar was sued in the Hague. By this time, Myanmar corrected its posture a bit, probably taking the advice of Japan, and a new explanation was chosen, which was that although the military had acted excessively, it was of a defensive nature, not genocide.

And Japan basically starts by supporting the narrative spread by the Myanmar state and shapes the facts to the extent that Myanmar must respond to “allegations of human rights violations” in the future.

This protest before the MOFA was not the first protest by the Rohingya in Japan. In the past, the Burmese Rohingya Association targeted Myanmar, their home country, not Japan, where they had long stood in front of the Burmese embassy in Tokyo to support Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD, and initially they had acted alongside the Buddhists and the Burmese. Around 2005, the emergence of extreme nationalism in Japan’s Buddhist Burmese community halted Rohingya linkages with the Burmese community.

The Japanese who have supported the lives of the Burmese Buddhists in Tokyo will never forget the disheartening experience of the 2012 conferences between the Buddhist Burmese community in Tokyo and Japanese supporters on the current human rights situation in Myanmar. As they were supposed to be friends with each other, and the latter often financially supported the former, the former should have appreciated what the latter had done to them, but the moment one of the Japanese speakers started talking about Rakhine State and uttered the word “Rohingya,” a Burmese from the audience roared, “There is no Rohingya group in Myanmar.” The Japanese facilitator intervened with determination and calmed the dismayed crowd.

It may sound strange that the propaganda rhetoric that the Burmese military has been teaching the Burmese people for many years has come out of the mouths of the Burmese who fled the military to came to a foreign country to continue their protest against the military, but this kind of claim of Buddhist Burmese refugees is common to Buddhist Burmese not only in Japan but also in many foreign Burmese communities. It may have affected the Japanese people’s view on the issue. Some Japanese understand the history and current situation through Buddhist Burmese in Japan, and do not know or want to know about non-Buddhists in Myanmar The propaganda that the Rohingya are intruders from the days of British rule may be more acceptable to relatively uninformed Japan when it comes out of the mouths of Burmese Buddhist immigrants protesting the Burmese military.

For an average Japanese, it is difficult to imagine a society in which the dictator can so successfully disunify the minorities. rights of minorities are so blatantly violated or the discriminated.

The Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, seat of the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

Ⅱ.The ICJ

The Rohingya’s January 2020 protests in front of the MOFA were triggered by the remarks of a single Japanese man. In late December 2019, the Rohingya were awaiting a decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on interim measures concerning the Rohingya Genocide around the world. If the ICJ approves the interim measures sought by the Gambia, that decision will be the first ray of light on the Rohingya issue since 2017. Shortly thereafter, the Japanese Ambassador to Myanmar made in Yangon an unexpected and undiplomatic announcement that spread around the world. He summoned Radio Free Asia and other reporters to the Japanese embassy and said in front of them,3 “We fully believe that there is no genocide in Myanmar.” “We pray that the ICJ will not make a decision on interim measures.”

Before we can understand the implications of this interventional action, we need to take a look back at Japan’s involvement in this genocide issue. Between 2017 and 2018, with respect to the implementation of the recommendations of the Annan Report submitted to Myanmar in August 2017, an investigation was conducted by an advisory committee chaired by former foreign minister of Thailand, Surakiat Sathiratha, but two members resigned one after another and publicly referred to the committee as a “whitewash.”4

In 2018, Myanmar established a separate commission called the Independent Commission of Investigation (ICOE) on the 2016-2017 Rakhine State incident, to counter the previously published UN Fact Finding Mission report alleging genocide. The final report was expected to be submitted by the second half of 2019.

In the course of the UN Fact-Finding Commission report, which gathered vast amounts of information to confirm the existence of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, Myanmar refused to cooperate with the commission’s investigation, and despite its own unjustifiable refusal to cooperate with this report, Myanmar ignored the resulting report as one-sided. If Myanmar had been able to provide a reason for its refusal to open Rakhine State to the Fact-Finding Mission, Myanmar might have been able to maintain even a modicum of credibility. The following questions immediately arise.

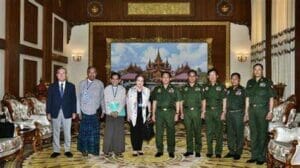

(1) The ICOE’s investigation has been based on the premise that since its inception, the State has been conducting simply clearance operations, and that this is not a state crime. Neither State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi nor Commander in Chief Min Aung Hlaing seems to have thought that the ICOE might condemn them. This is a strange assumption but the photo below means that they are sure.

The photo above shows the ICOE commissioners alongside the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Min Aung Hlaing.

Standing in the center in green uniform is the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces Min Aung Hlaing, on his left is ICOE Chairman Rosario Manaro, on her left are the Burmese ICOE Committee Members, and the leftist is ICOE Commissioner Kenzo Oshima. (”Independent Rakhine Commission of Inquiry holds two-day meeting” Radio Free Asia May 4, 2019 )

(2) Can a very small ICOE organization consisting of only four members challenge the accusations made against Myanmar based on the pile of evidence collected by the UN Fact-Finding Commission? Presumably the ICOE had judged that it was pointless to try to disprove these accusations and that it orchestrated a cover-up of the truth while borrowing legitimacy from two foreign countries, Japan and the Philippines.

(3) Given the precedent of the Surakiat Sathirathai Commission, is it natural to presume that the ICOE has effectively been entrusted with” whitewashing” again? How can a report from four people who were willing to be in the same picture with the criminal leaders claim to be superior to a report from the UN, and if this logic makes sense, why did Myanmar not think that it would be better to ask the people of Rakhine State to find out what was happening in Rakhine? Most dubious was Myanmar’s request to a former foreign ministry bureaucrat Oshima Kenzo, who was a former ambassador to the United Nations, to join the ICOE as one of the two foreign members.

Officially this is not a deal. Whether or not Myanmar and the Japan saw it as an issue independent from bilateral relations is too important to be revealed. The official explanation of the Japanese government is that Myanmar chose this former ambassador and that the Japanese government has nothing to do with this selection. Even if this is the case, since Japan has supported Aung San Suu Kyi and Myanmar’s position with regard to Rakhine State, the role of this former Japanese official expected of Myanmar will depend on both the person who was asked to take office and the Japanese government.5

It was clear from the outset that the ICOE (Independent Commission of Enquiry) was actually a NICOE (Non-Independent Commission of Enquiry), an investigative committee not-independent of the state of Myanmar. It rejected reasonable guess and credible research by foreign countries and NGOs in the name of independence, and it asks no question about the independence from the power of the Burmese state. Here the concept of independence from its colonial status has been replaced with anti-Westernism to support the dictatorship.

During the gathering process, the chair, Rosalio Manalo, a former Philippine diplomat, held a press conference and stated that the Committee had not yet collected evidence of human rights violations and that those who possessed the information would need to present evidence and notify the ICOE. 6

If this chair had not done all these special preparations for her original black humor, this episode shows how much knowledge the ICOE chair from the Philippines actually had about how much freedom of speech there actually was in a Myanmar where correct speech and information about persecution in Rakhine could cost the lives of speakers.

It was in November 2019 that the Gambia filed a lawsuit against Myanmar on account of genocide in the International Court of Justice. By then, Myanmar was supposed to complete the ICOE report, but the conclusion was delayed without explanation. and after the case was brought to the ICJ, Japan’ ambassador to Myanmar issued in Yangon the aforementioned comment. It is clear that the ambassador took the matter of the ICJ’s trials lightly.

Based on the voluminous report of the UN Fact-Finding Commission, which cannot be refuted by a brief unprofessional comment of the ambassador, who is a friend of Myanmar, the Gambia took this issue to the international court. While this UN report is a rigorous process to be based on careful evidence gathering, the Japanese ambassador did not mention facts at this press conference, and used the flimsy subject “we”. The first question is what he meant by the vague subject “we” when he said, “We believe that there is no genocide in Myangmar”? Did he mean the Japanese people, the Japanese government, or the MOFA?

Second, if Japan or the ambassador recognized that it was futile to try to change the course of the ICJ, who was he trying to influence – Is it the Gambia or any other country in the Organization of Islamic States? Is this an expression of opinion or a euphemistic threat?

Third, does this ambassador’s bold and insane action mean that the Japanese as a nation wanted to express its opinions, or is it an independent decision by the Ambassador or the MOFA? This statement from Yangon seems to have been overlooked by the Japanese press, and even the foreign minister of Japan did not seem to have been properly informed of the ambassador’s remarks. Japan’s foreign minister Motegi’s reaction at the subsequent press conference at the press club7 proved that the foreign minister had little knowledge about the preceding provocative statements of the ambassador.

Rohingyas at the Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh, October 2017. Wikipedia Commons

Ⅲ.Press Conference

1.

At a press conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Press Club of Japan,8 BRAJ (Burmese Rohingya Association in Japan) President Zaw Min Htut, thanking Japan for helping the Rohingya community, expressed strong disagreement with the MOFA. He said;

-

- Myanmar denies the Rohingya ethnicity and citizenship with the single word “Bengali”. It is unfortunate that the Japanese ambassador is using this designation that State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi does not use. This is a labeling that discriminates against the Rohingya.

- The Japanese ambassador to Myanmar does not regard 2017 as genocide. But genocide has a long-term process since 1962.

- The new phase of war between AA (Arakan Army) and Myanmar killed many Rohingya trapped between the two.

- Many Rohingyas are trying to flee, but are caught and put in prison.

- Not only is there a devastation of IDP (Internally Displaced People) camps, but the villages of Rakhine State are like open-air prisons.

- “I have been asking Japan to support the Rohingya for the past 20 years, but Japan does not support the UN’s action against Myanmar. In response to our protests, Japan says it is talking with the Burmese government.”

- Myanmar’s junta keeps lying to the international community.

- Not only the Rohingya but also other Burmese minorities such as Kachin, Shan, Karen, Kaya, Chin, Mon and some Rakhine are suffering. The Rohingya, after 50 years of hard work, still need to seek justice in international societies because they are not expected to get justice at home, and I hope that Japan will not side with the criminals.

- When the Japanese ambassador visits Rakhine State, he speaks with the Rohingya, who have actually been selected more than a week in advance and have practiced answering questions, which is a method that has been used in the country since 1962. After taking power, Aung San Suu Kyi looked away from the Rohingya who had supported her. She lacks the will to properly handle the Rohingya case; she is only relying on the military to maintain her power. She went to the Hague for the ICJ with the next election in mind, but democracy and peace cannot be built on a mountain of Rohingya bones. Without justice, there is no peace or democracy.

- Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom supported the Gambia, and I hope the United States will do the same.

2.

After President Zaw Min Htut, in the same press conference, this author who has been collaborating with him in recent years in lobbying the MOFA on the Rohingya issue, said;.

-

- Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing came to Japan in early August 2017 to meet Prime Minister Abe. After returning home, he ordered the light infantry divisions to be sent to Rakhine State and soon launched a so-called clearance operation on August 25. Of course, the Commander-in-Chief must have made this important plan for what was to be done in Rakhine State by himself when he met Prime Minister Abe. Timely enough, Prime Minister Abe said at the meeting that he expected the “leadership” of the commander-in-chief.9 Yes, the commander-in-chief would send two divisions to Rakhine State in advance for short-term use, which is an extraordinary “leadership” like a fortune teller seeing the future in a crystal ball. It would not be surprising if a public debate had started in Japan about the true meaning of this visit to Japan by the Commander-in-Chief, but no question is asked yet.

- During the military campaign in Rakhine, the Commander-in-Chief announced in Burmese on Facebook that the military was responsible for an “unfinished business.” Since it was the Facebook of the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, the Japanese Embassy in Yangon would have known this, and if they had known, it was knowingly not trying to stop it, but it continued to cooperate with Myanmar, which is a part of the process of genocide. If it did not know, the Japanese embassy in Myanmar is incompetent because it could not know, even when the killer was coming out and self-justifying himself.

- Since August 2017, the Japanese government has expressed its condolences based on reports that several Burmese soldiers have been killed, but it has not until now expressed its condolences for the Rohingya victims. If you visit the MOFA of Japan, you find the funny position of the Japanese government. With respect to the damage from the “terrorism” of the ARSA, Japan accepts it as a fact because Myanmar recognizes it, and with respect to the point that the Rohingya people have been killed in cruel manners in huge numbers, Japan regards it as allegation because it has not been confirmed by Myanmar. Yes, you should ask a criminal in order to know what happened and who did it.

Picture of a Rohingya Child, (Kutupalong, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh 2018) (The author visited a camp for Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, with my assistant – a young man who is Rohingya, and simply said to the Rohingya children of the upper grades of elementary school there, “Explain to me with a picture why you are here now,” and handed them 12 colors of crayons and drawing paper. Thirty minutes later all the children in the classroom submitted their drawings, and here is one of them: the severed hands, feet, and neck of the woman’s body were colored green, and the clothes and swords of the arson behind her were also blue and green, which seems to imply that it was the work of the Burmese army in green uniform. Remembers the photos of the Burmese military and the ICOE members.

- Since 2017, human rights violations against the Rohingya in Myanmar have been characterized as “allegation” for the Japanese government, but if you believe the language of this government, you should look at one picture depicting at my request what happened. It reveals details that only witnesses can express, such as the mutilation of corpses.10

- Since August 2017, Japan’s policy toward Myanmar has been to “think together” with Myanmar and to “support nation-building.” These phrases are used even after the massacre of Tula Tuli.

- There is a big difference between Canada, which sought to end the genocide in Myanmar, and Japan, which continued to call the same situation an “allegation” of human rights violations. If Myanmar denies facts about Myanmar, how can foreign countries confirm the facts about Myanmar? Myanmar’s refusal to conduct a domestic investigation increases the authenticity of the victims’ testimonies. If Myanmar does not let the UN Special Rapporteur or a UN fact-finding mission for investigation in Rakhine, the world naturally assumes that the truth must be inconvenient for Myanmar. But Japan does not seem thinking this way.

- There is an interesting twist in the use of the term Rohingya or “Bengali” in Japan.

(a) Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono stated in his blog11 that Japan does not use the term Rohingya or “Bengali” for the sake of neutrality.

(b) But this point contradicts the fact that the MOFA of Japan signed an Exchange of Notes with Myanmar in 2013, which is referring to the conflict between the Rakhine and “Bengali“ Muslims.

(c) The Ministry of Defense of the Japan uses the term Rohingya.

(d) As known, the Japanese ambassador in Yangon used the term “Bengali” at least several times before the Burmese press and the foreign press. Because he used “the Rohingya”, before the Japanese, he duality of Japan is difficult to notice for the Japanese. - There are two pillars Japan often depends on to explain its Myanmar policy to the Japanese.

(a) Aung San Suu Kyi is the heroine of the human rights and democracy, fighting a difficult battle against the military.

(b) If Japan forces Myanmar excessively, Aung San Suu Ky’s position in the state will be endangered and Myanmar will go back to square one. - As Foreign Minister Kono once said, Japan may be trying to protect and nurture the fragile blossom of Burmese democracy. Since Myanmar is an inchoate democracy, the world needs to be tolerant to it, and punishing Myanmar will weaken the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, a military coup could occur, and the world will lose all past progress in Myanmar. But this is only an excuse, because Japan has never proposed a roadmap for change in Myanmar. Canada has at least said that Myanmar should respect diversity”, pointing out observable gaps in Myanmar’s current democratization process. The fact that Japan fully entrusted the democratization of Myanmar to Myanmar and that Japan is trying to appease criminal Myanmar means that Myanmar will learn the lesson that Japan will tolerate future crimes, which in turn increases the likelihood of a military coup in the country.

- Japan can be interpreted as contributing to Myanmar’s interests because it knows that it can be replaced by other countries because it is becoming less and less outstanding in Asia.

① Compare Myanmar with South Africa under Apartheid. The UK is South Africa’s best economic partner, and when the UK moves to change the South African system, at that time there was no other option for the latter than to concede and reform, South Africa could not replace Britain with China at that time.

② But in modern Myanmar, if Japan is leaving it, there can be an alternative which is asking China to fill the void by increasing its support for Myanmar. Therefore, as long as there is China for which business and human rights are seen as separable, Japan’s efforts to change Myanmar will be futile and contrary to the interests of Japan.

③ In order to compete with the thriving crony business in Myanmar, Japan needs to be close to Myanmar.

④ The Japanese business community likes to enter Myanmar in this way, and Japan as a state understands that the implicit message is being sent from the entire large corporate community. Since the public and private sectors are cooperating for economic expansion into Myanmar, this does not need to be confirmed. Both the public and private sectors generally underestimate the risk of expansion. Therefore, the Japanese business community, without saying a word, can move the Japanese government closer to Myanmar. - Myanmar is also preparing various schemes to deny the existence of genocide, some of which is played by highly ranked monk Sitagu Sayadaw, who in his talk after several massacres in Rakhine in summer 2017 that a monk appeased a Buddhist king when he was heartbroken by the murder of many non-Buddhists in ancient Sri Lanka. That is, as the life of a non-Buddhist is much lighter and more insignificant than that of a Buddhist, killing a large number of pagans does not mean killing a person. This was the blatant message of his talk. It was all military personnel who were sitting in front of him and listening when he gave this talk. I wonder if the meaning of this talk broadcast on the stream is included in the analysis of the situation at the Japanese embassy in Yangon. If the Myanmar military itself believes in the explanation which the Japanese government kindly repeated that there is no genocide and the human rights violation is only allegations, why is it that Sitagu Sayadaw, the semi-official monk of the armed forces, tells the soldiers such a shameful and unprofessional story before a large audience and the story is circulated throughout the country?

- If Japan sincerely regrets the crimes against humanity during World War II, should Japan not think ahead of other nations that it must know, solve, and judge what has happened in Rakhine State? Should Japan not have the will to catch the sign of approaching tragedy and prevent its start? Should Japan not have the idea of Genocide Watch, irrespective of whether the Chinese explanation of the Nanking Massacre is correct or not? And the current ASEAN countries, which do not forget the atrocities committed by the Japan to themselves during World War II, cannot avert their eyes from similar cases occurring in the countries of today’s ASEAN.

Aerial view of a burned Rohingya village in Rakhine state, Myanmar – September 2017. Wikpedia Commons

Ⅳ Domestic Actors Rohingya face in Japan

Bureaucrats

Zaw Min Htut has been visiting the MOFA for nearly 20 years since his arrival in Japan, in cooperation with some Japanese and international NGOs. and the author of this article has also participated in his activities for the past few years. Although the MOFA has responded carefully to Zaw Min Htut, he was initially only allowed to lobby for about 10 minutes at the MOFA when there were no statesmen as intermediaries.

Later, after he had begun to be able to enlist the help of a very small number of members of the Parliament he was finally able to have one-hour meetings with a few relevant government officials. The people that bureaucrats need to respect in their duties are parliamentarians and ministers. If legislators want to visit oversea countries, the MOFA people listen to their aims and opinions and plan their places and dates.

For Japan, Myanmar policy belongs to a priority area, that is, policies that promote economic penetration into Myanmar are being pursued by the political party in charge. The Rohingya problem lies under this large structure, which gives the bureaucracy the power to continue to maintain the current pro-Myanmar policy. Japan bureaucrats know that the expression “think of national interests” is useful when you want to disregard the interests of minorities from the perspective of Japan, the expression that “Japan is not a nation that can do anything, what can Japan do?” is useful when Japan wants to maintain involvement in the economic sphere, and “peace” is useful when you do not want to have a rocky relationship with anyone, including thugs.

There are two main possibilities to change this bureaucratic inertia, one is that Myanmar itself will voluntarily change, which is currently unimaginable. The other is the possibility that Japanese politicians will be more interested in human rights in Myanmar, but this is also unimaginable because it is unlikely that politicians will take human rights seriously unless to do so is rewarded in elections. It means the possibility that politicians get less support of the people.

As long as the decision does not contradict the wishes of the major political parties, the Japanese bureaucracy will satisfy the Cabinet and satisfy Myanmar with more passivity than is required by calling the Rohingya “Bengali” behind the scenes and refraining from the UN’s condemnation of Myanmar. In a sense, the dog does not wag its tail, and the tail is wagging the dog. Respectful obedience to the criminal state of Myanmar continues at the core of Japan’s Myanmar policy, in which the assumption that Myanmar as a fragile democracy is held without evidence. There the heroine Aung San Suu Kyi is supposed to be fighting cautiously against the military for the true democracy Japan is eager to protect.

MOFA bureaucrats change their departments every two to three years, which means that each department of the MOFA does not have much organizational memory of the details of their duties. They do not remember what a person in their department spoke to an NGO a few years ago, and every few years it is necessary for the lobbying to re-explain the situation from the beginning. And even if there are few bureaucrats who are distressed by the Rohingya or Myanmar issues, they only need to wait two or three years to be freed from their remorse.

One of the main job-openings for Myanmar-related or Burmese-speaking bureaucrats after retiring from bureaucracy is to be rehired by large corporations seeking opportunities to expand abroad, including Myanmar. It can be expected that they do not want to steer Japanese foreign policies to the direction of dissatisfaction of large corporate groups which are their future employers. Several important factors accelerate their enthusiasm.

The first is the predictable contraction of the Japanese market. With the aging and declining population, the Japanese industries need larger external markets in all areas, including beer, soft drinks, automotive, railroads, telecommunications, and other infrastructure, and so forth.

The second is the cooling of Japan-China relations due to the territorial dispute and the decline in China’s economic growth rate. China is less comfortable for the Japanese industries and less profitable than before.

The third is the relative decline in the competitiveness of the Japanese industries as the Chinese economy intensifies its expansion into Southeast Asia. Japan’s industrial technology is no longer irreplaceable. China’s political and economic culture symbiotic with a region like Cambodia that has a relatively loosely controlled political and economic culture. If Japan were to move Myanmar toward a more humane policy for minorities, Myanmar would dislike hard orders, and China could replace Japan with its own industrial status, as happened in Cambodia.12

The bureaucrats believe that they are tasked with supporting the Japanese industry and that they need to respectfully support Myanmar, including information for self-justification coming from Myanmar. So bureaucrats can continue to operate as usual until the “allegations” are no longer “allegations”. In this way, the interests of the Japanese industry cohere with the self-interest of the bureaucracy.

Where are the politicians? The majority of members of the Parliament repeat the urban life of Tokyo and the local life. They spend half the time each week in their electoral districts and half the time in Tokyo. Local meetings await them in their constituencies on weekends. Legislators need to join them in order to remain remembered and re-elected by their supporters and seen as important and trustworthy. The ministers and deputy ministers cannot escape this communication.

The deputy minister of foreign affairs may visit the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, for example. It is easy to imagine that what he says in his speech in the camp has not exceeded what MOFA bureaucrats have prepared for him. Upon return to Tokyo he immediately participates in a local summer festival in his district. Even if he learns of the misery of the Rohingya in a camp in Bangladesh, his precious memory about the globe could evaporate or be replaced, before it is released for the public, with the memory of the fantastic fireworks of the local summer festival.

A politician too afraid of losing the next election will not learn much. Of course, the human rights of foreigners is a subject that does not guarantee electoral victory. But this is particularly so in Japan. In countries with big social diversity, the value of universal human rights is widely recognized, but it is not the case in Japan. When their boss is so locally oriented, the bureaucrats have little obligation to be otherwise.

If Japan in this way is free to seek its economic interests at the sacrifice of the human rights in Myanmar, why, then, does it need to be so sensitive to its history of human rights abuse during WWII in Asia? Perhaps this is because the past plays the role of a decoy to divert attention from the present.

In this regard, Asian countries are cooperative, and China will never say why Japan protects criminal Myanmar now. And Europe and the US, which are democracies supposed to share fundamental values with Japan, do not warn Japan about the present dubious move of Japan. China takes the position that it was a victim of human rights abuse in the past. So do many other countries in Southeast Asia including Myanmar. Japan takes the position that it was a human rights violator in the past. This is less painful than to admit that Japan is an accessory to human rights violation now.

Where is the press? There are two types of mass media customers. The first is a group of companies that pay for advertising for business gain. It is possible for the media to publish speech that is contrary to the interests of the company, but speeches hostile to the entire business community from which the media derives advertising revenue is dangerous for the media.

The image of Aung San Suu Kyi as a symbol of democracy and human rights started crumbling with the intensification of the persecution of the Rohingya in Rakhine, before her emergence as the State Councilor. But since the entire Japanese business community sees Myanmar as an opportunity, the government of Japan kept reminding the public of the myth, and the Japanese media was cooperative to the misguided process.

The following editorial in newspaper Kyoto Shimbun is one of the editorials calling for reform in foreign policy in Japan on the Rohingya issue, but it recommends a policy of engagement rather than confrontation with Myanmar.

“Rohingya persecution relief is an international request”

The return of refugees has not progressed at all, and many remain forced to live in poor conditions. Myanmar does not recognize the Rohingya as their own ethnic group and does not even give them nationality, so there is a risk of persecution again after their return. It is necessary to create an environment where refugees can return to their homes with peace of mind Although Japan understands Myanmar’s claims to a certain extent and maintains friendly relations, there is criticism that the pursuit of economic interests is prioritized over human rights. It is essential not only to provide economic support but also to actively encourage the return of refugees. I would like the Japanese government to cooperate with the international community and induce Myanmar to recognize citizenship and grant rights to the Rohingya.13

It is important to note that the above editorial calls on Myanmar to grant citizenship to the Rohingya argues that economic support from Japan is not everything. However, this editorial merely wants Japan and Myanmar to change. The point that Japan is not exerting as much pressure on Myanmar as possible is concealed in this editorial.

Like many other Japanese editorials, this editorial translates genocide as “ethnic mass slaughter,” but genocide is a more complex concept of processes than killing a large number of people, and this translation is insufficient, if not inaccurate. If the role of the media is to stimulate public consciousness, it would have been the obligation of the press to let the public know that the MOFA is a kind of genocide denier clearly standing with the Burmese military.

Even though the media says that the Japanese government should demand that Aung San Suu Kyi play a more active role in the Rohingya issue, the media has also refrained from making more specific criticisms. It does not say that Japan should stop abstaining from the UN Human Rights Council resolution on the Rohingya. The relationship between the state, the media, and the government in Japan may be staged by the media to fabricate a hypothetical national consensus on state policy, just as Noam Chomsky14 called a “tactical debate” by the media. Both the state and the press have the same clientele of the business community, and the state knows that state silence to the ritual criticism of the media will not be severely condemned by the media, and the media also knows that it will not push the state an inch.

Where is the public? The second group of customers are the purchasers of the press. The first problem with them is that the population that purchases the products of the press, such as newspapers and TV programs, continues to decline. The second problem is that readers do not want to be unhappy. When Western citizens learn of the persecution of the Rohingya, attention is turned to the persecution of the minority groups, which make people recall their buried national experiences of the past. In other words, the narratives of modern history of Europe and the US can resonate with the narratives of liberation in developing countries.

In the United States, for example, the current “Black Lives Matter” movement can go back beyond the civil rights movement to the long history of the abolitionist movement and the Revolution. The Bangladeshi may compare the Rohingya’s struggle against Myanmar with Bangladeshi fight against West Pakistan.

In contrast, Japan assumes that someone will come up with a solution to the problem and Japan will contribute to it, and Japan applies the framework to cases in its neighborhood.

Ⅴ. Human Rights, Justice and Defeat in World War II

Japan has four characteristics of modern history that differ from those of the West. First, it does not have a radical change in the view of humanity and the revolution that accompanied it, such as the emancipation of slaves and the revolution of independence, and they have a poor history of overcoming human rights violations in their own societies with their own power.

Second, crimes against humanity, in its most undisputable term, were inflicted on Japan in the form of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the carpet bombing of most major cities in the final stages of World War II. The Japanese were forbidden to condemn these as criminal, and publications on these in Japan were censored. Japan was tried before international tribunals for crimes against humanity. These trials and the experience of the American occupation may have caused a noticeable distortion in the evolution of Japan’s political thought. Since the concept of “justice” is easily used politically and for the convenience of the power-holder, one of its characteristics is the inclination to avoid “justice” excessively, for fear of being seen as double-standard.

Third, since the end of WWII, the Japanese have been trained to ascribe all serious international problems to a lack of peace. They were willing to learn that way. In the case of atomic bombs, Japan did not blame the United States for dropping them, but condemned the lost peace caused by the preceding war with China and the attack on Pearl Harbor as distant causes for the final calamity. For an ordinary Japanese, all wars are bad, and all peace is good. Assuming that the persistence of human rights issues in some countries is due to the lack of peace, the Japanese people try to prescribe more peace to overseas human rights problems.

This twisted thought is partly due to the result of a long period of peace bringing prosperity to the post-war Japan, but what is lacking in this thought process is the question of who is violating the lives and livelihoods of whom. Because of this intellectual inertia, the Japanese try to prescribe peace and prosperity to the Rohingya issue. One of the typical attitudes of the Japanese is found in the flow of thought this author experienced in the questions at a 2015 seminar on how to deal with the Rohingya crisis in 2012 -13.

At a seminar on the Rohingya held at this author’s university, an elderly Japanese man raised his hand and asked, “If Myanmar strives to continue economic development with the help of many countries like Japan and the growth effect eventually trickles down to the minority, won’t the problem of discrimination in this country disappear?”

In response to this question, Zaw Min Htut, then a speaker in this seminar, and this author, who was the moderator, said almost unanimously, “In the case of Myanmar, the carrots of prosperity and peace will escalate the movement to oust minorities. By the time the trickledown reaches the bottom of Rakhine State, the Rohingya in Rakhine State will have been all killed. We can’t imagine that the Deus Ex Machina of prosperity and peace will eventually bring a happy end.”

Fourth, when the notion of crime against humanity was first introduced into Japan’s history, the Japanese viewed them with skepticism. The manner in which the Tokyo trials were conducted after World War II may have affected the subsequent Japanese views on crimes against humanity. “Crimes against humanity” corresponds to class C of Article 5(2) of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

Before the end of World War II, the leaders were tried at the Tokyo Trials for crimes against peace (Class A), but some leaders were also prosecuted in Class C. Class C. was mainly handled outside Japan, and its fact checks were rather inaccurate. Many Japanese were mistaken for criminals and executed, and many superiors shifted their responsibility to their subordinates. Many have given up without self-defense. It is possible that the Japanese learned more about the carelessness of their condemnation than the importance of crimes against humanity, along with the misery of their own defeat. Seeing hypocrisy of the victors behind the notion of crimes against humanity, some Japanese may sympathize with Myanmar in defiance of the west.

“They are forced to lead sub-human lives, with no freedom of movement, no prospect for third country resettlement, no Internet, no electricity, no proper schooling or livelihood opportunities.” Daily life of Rohingya refugees at Balukhali Camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh on February 02, 2019. Photo: Sk Hasan Ali / Shutterstock.com

Ⅵ.Conclusion

Because the interests of bureaucrats, politicians, the media, and the business community coincide, the morality of the Japanese companies doing business with Myanmar where genocide against the Rohingya is ongoing is not so much questioned. There is no reason why only the Rohingya in Japan should fight on the frontlines of protests against the Japanese state.

The Japanese people should be nauseous at the fishy smell of their own country supporting genocide in Myanmar using a development narrative. However, Japan once accused of crimes against humanity could not develop national consciousness on human rights. And the Japanese public is yet to be free from the information control of the state. In this sese, the tradition of Great Headquarters Announcement, the state framework to produce lies too big to be noticed, has survived.

If tomorrow, the prime minister and foreign minister of Japan identify the “Muslims of Rakhine” as the “Rohingya,” the position of the Japanese government meets some of the requests from the Rohingya. But they do not. Japan’s policy on the Rohingya camps in Bangladesh is a humanitarian policy to help 1 million people, but it also conceals the essence of the role of Japan which has emboldened Myanmar to the present extent.

The Rohingya community knows that the past and present of their complicity in Myanmar and the perpetrators of genocide who ordered their past actions in Rakhine State may be concealed by this support. But the average Japanese public has not received information from those who are in power, the business community, mass communication, and bureaucratic groups, enough to see a virtual deal in this set of humanitarian assistance.

The people of the MOFA received envied education, in an era when state diplomacy and its employee’s self-preservation intertwine with one another. The fusion of state interest, bureaucrat’s interest, corporate interest and self-interest leaves little room for ethical sensitivity toward the persecution abroad. The MOFA officials are trained to be sensitive to the unuttered will of the political and business community and insensitive to the uttered protest from the community of the discriminated. What the elite of Japan acquires as a result of his education and training is a banal fear of losing something trying to bring justice.

This may also be due to the weakness of Japanese elite education beginning in childhood, which asks not how to set up a problem, but how to envisage model answers and whom to assume as the grader. The Rohingya protesters, wise enough not to be swayed by undue optimism, can reject the sugarcoated Machiavellism of the MOFA. But they have no way to know how to orient this Japanese conglomerate of interests toward the intangible value of human rights.

When the MOFA bureaucrats in Japan “cuddle” with the attackers and stay away from the protesters, the MOFA is a very predictable actor taking all as routine, even a crisis. From ODA to ICOEs, the MOFA loyalty to the existing power prevails. But its dubious morality is kept surprisingly unnoticed in the public opinions of Japan. The public can be indignant of the petty bribes high-ranking people might have received, but stay perfectly calm with the news of their prime minister having met with the Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese military shortly before the deaths of thousands of Rohingyas in Rakhine.

Unless a Japanese member of the Parliament sees beyond the fireworks of his local town summer festival the unforgettable destitution and unremembered deaths of the camps in Sittwe or Cox’s Bazar, unless Japan’s leader thinks about what they must do if he has to face the problem alone, unless the Japanese public respects such an indignant politician, unless the media in Japan can be less communal and more relentlessly seeking truth and justice in the areas of foreign affairs, the Rohingya’s disappointment will deepen, in the ocean of Japanese complacency.

While sympathizing with these Rohingyas, the Japanese public cannot comprehend the depth of their disappointment. As long as the Japanese fantasize that the distribution of more bread will put an end to hate speech circulating in Myanmar and bring dignity to the oppressed, Japan cannot be expected to play a leading role in the field of human rights. Probably it is better to regard Japan not as an international “contributor” to the implementation of an effective and legitimate solution, but as an accessory to the perpetrators of genocide, “contributing” to anyone, regardless of who they are, to pursue its own interests.

Donald Trump’s way the U.S. initiated targeted sanctions against China is worth learning to apply. By imposing sanctions on Japanese businesses that still associate with the criminal state of Myanmar, the U.S. and Europe can make Japan and its industries pay the price for the desires hidden behind their pretensions of peace and prosperity.

Michimi Muranushi

Department of Law, Gakushuin University, Tokyo

- This is an English translation of this author’s article originally written in Japanese, “弱者の非凡と権力者の平凡;日本のロヒンギャコミュニティと国家」(学習院大学法学会雑誌2022年3月)“The Exceptionality of the Powerless and the Banality of Power: Japan’s Rohingya Community and the Japanese State” Gakushuin Review of Law and Politics, March, 2022 which is based on this author’s talk at the online conference in August 2020 “Connecting the Rohingya Diaspora: Highlighting the Global Displacement”(the Centre for Genocide Studies, University of Dhaka,August 25-26 2020)

- The Japanese government’s designation for the Rohingya contains duplicity that is difficult for the general Japanese society to notice. The Japanese government allows the media to use the term Rohingya. Of course, the government does not have the authority to prohibit the use of certain terms. The members of the Japanese Parliament also use the term Rohingya, but ministers, and MOFA bureaucrats do not use this term themselves.Other Japanese ministries, such as the Ministry of Defense, use the term “Rohingya.” According to the official view, Japan for the purpose of being fair between the Rohingya and Myanmar, uses neither the “Bengali” (a term with a derogatory connotation in Myanmar) nor the Rohingya (a term by which the Rohingya identify themselves), However, the Japanese Foreign Ministry uses the term “Muslim Bengali” in the 2013 Exchange of Notes between Myanmar and Japan. “Signing of an Exchange of Notes on Grant Aid to Myanmar,” MOFA of Japan, March 22, 2013. Also, Japanese Ambassador to Myanmar as of 2020, his excellency Ichiro Maruyama, uses the word “Bengali” as a word meaning Rohingya in his comments in Burmese or English. Most Japanese do not know that the ambassador, outside Japan, refers to the Rohingya as the “Bengali”.

- “Japanese Ambassador Voices Support For Myanmar on Genocide Charges” Radio Free Asia Dec. 26, 2019 https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/japanese-ambassador-voices-support12262019163626.html

- “Exclusive: Richardson quits Myanmar’s ‘whitewash’ Rohingya crisis panel” Reuters, January 25 2018 URL Exclusive: Richardson quits Myanmar’s ‘whitewash’ Rohingya crisis panel | Reuters

- Former UN Ambassador Kenzo Oshima, who became a member of the ICOE, explained in Japanese to mainly Japanese viewers what happened in Rakhine State in August 2017 in his speech on Myanmar in May 2021 (former UN Ambassador Kenzo Oshima and Councilor of Kyoto International Peacebuilding Center: “On the Myanmar Situation” Japan co-sponsored by the International Peacebuilding Association and the Kyoto International Peacebuilding Center): (URL Japan On the Situation in Myanmar” co-organized by the International Peacebuilding Association and the Tokyo Metropolitan International Peacebuilding Center, Friday, May 14, 2021 – Japan International Peacebuilding Association (gpaj.org))

- “Commission Invites Victims of Violence in Rakhine State to Submit Evidence” The Irrawaddy, December 12, 2018. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/commission-invites-victims-violence-rakhine-state-submit-evidence.html

- 「茂木外務大臣会見記録」Record of Foreign Minister Motegi’s Press Conference https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/kaiken/kaiken4_000913.html

- Zaw Min Htut and Muranushi: “Rohingya Crisis and Japan’s Denial of Genocide” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HmOzxOLx3PM

- 「ミャンマー国軍司令官等による表敬」2017年8月4日 Courtesy Call by the Commander of the Myanmar Armed Forces August 4, 2017

- [1]For details, see Michimi Muranushi “The Rohingya’s ‘Story’ and the Japanese Government ” (Seizanasha, 2020) These pictures are presented in color printing.

- いわゆる「ロヒンギャ」問題 河野太郎 The So-Called “Rohingya” Problem by Taro Kono https://www.taro.org/2018/03/%e3%81%84%e3%82%8f%e3%82%86%e3%82%8b%e3%80%8c%e 3%83%ad%e3%83%92%e3%83%b3%e3%82%ae%e3%83%a3%e3%80%8d%e5%95%8f%e9%a1%8c. php 162

- In this sense, Japan’s policy of tolerance toward Myanmar can be understood to be of the same kind as Japan’s policy of tolerance toward Cambodia. Michimi Muranushi “Reversal of Cambodian Democracy and International Relations” (Edited by Yoshifumi Nakai, “China’s Southbound Policy” (Ochanomizu Shobo, 2020)

- 京都新聞 社説:「ロヒンギャ迫害 救済は国際的な要請だ」2020年1月31日 Kyoto Shimbun editorial: “Rohingya persecution relief is an international request” Kyoto Shinbun January 31 2020

- Noam Chomsky “The US Media as a Propaganda System” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=viiww-9wN5c “The Manufacture of Consent” The Chomsky Reader (Pantheon Books, New York, 1987) pp.121-36