In the 1980’s Jack Healey was the man who took the Universal Declaration of Human Rights directly to the oppressed. In those days, the Amnesty International was the sole torch bearer. The Human Rights Watch, which evolved from the Helsinki Watch, the Cold War era anti-Soviet American NGO, wasn’t birthed yet.

Living in Washington, DC in the 1990’s, I had the privilege and honour of knowing, being guided by and working alongside Jack in the mid-1990’s. Jack had already vacated his position as the Executive Director of Amnesty International/USA, the leadership he had held for 12 years since the early 1980’s.

I was then running one of the Internet’s first and largest human rights campaigns in the world, with a singular focus on my deeply troubled birthplace of Myanmar (or Burma as I prefer to call it in protest of the junta’s changing the name to whitewash its bloody crackdown of our student-led People Power revolt in August 1988).

Jack showing me one of his treasures, a shirt gifted to him by the late (1974) Nobel Peace Laureate Sean MacBride, chief of staff of the IRA, External Affairs Minister of Ireland, who founded or participated in many international organizations including the United Nations and Amnesty International, in the basement of his Washington DC home, June 2019.

A former Catholic priest and a Franciscan friar with an Irish American background in the industrial city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Jack is passionate about music.

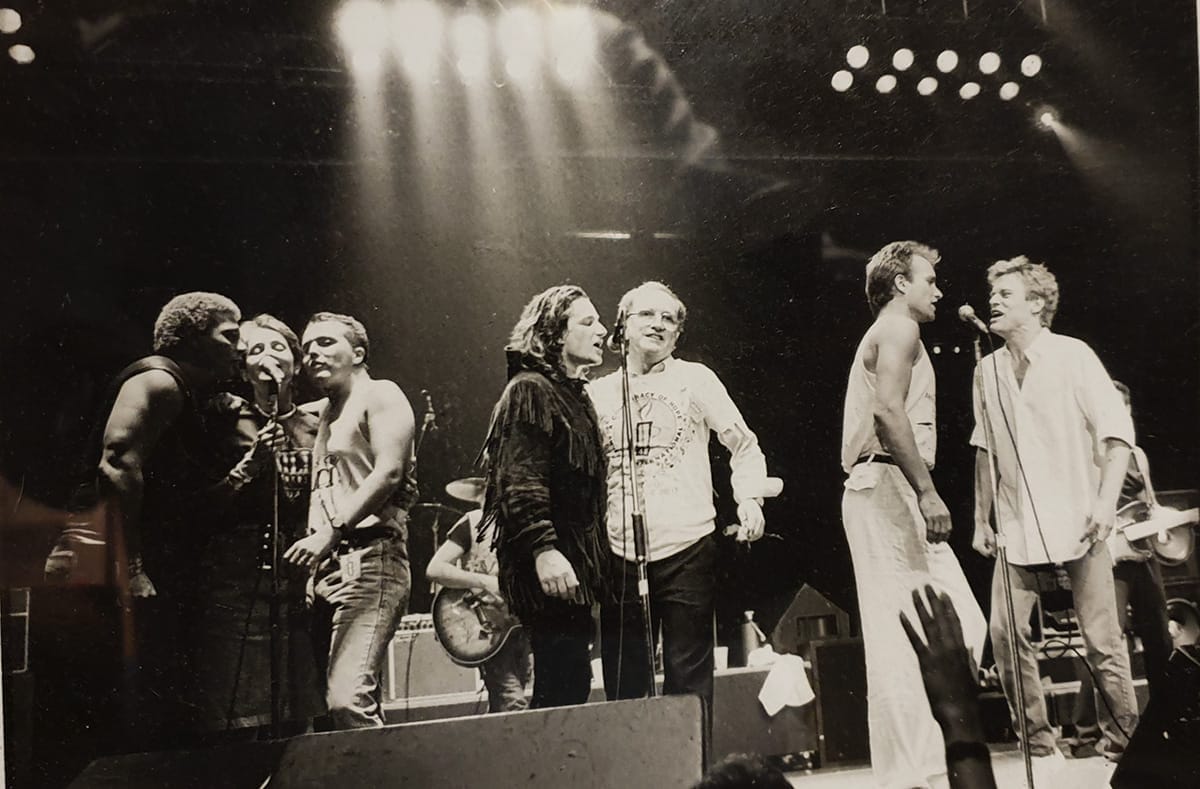

And he strategically adopted a mass communications strategy of using “pop” as a powerful vehicle to inform the oppressed around the world about their inalienable rights enshrined in the articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He reached out to his friends in the music industry and got some of the biggest names in the pop, rock and jazz world on board his mission: music for human rights. He organized highly successful concerts with bands like U2, the Police, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Sinead O’Connor, Bob Dylan, Santana, Tracy Chapman, Dave Matthew, Bryan Adams, Joan Baez, Lou Reed, Mile Davis, and many others.

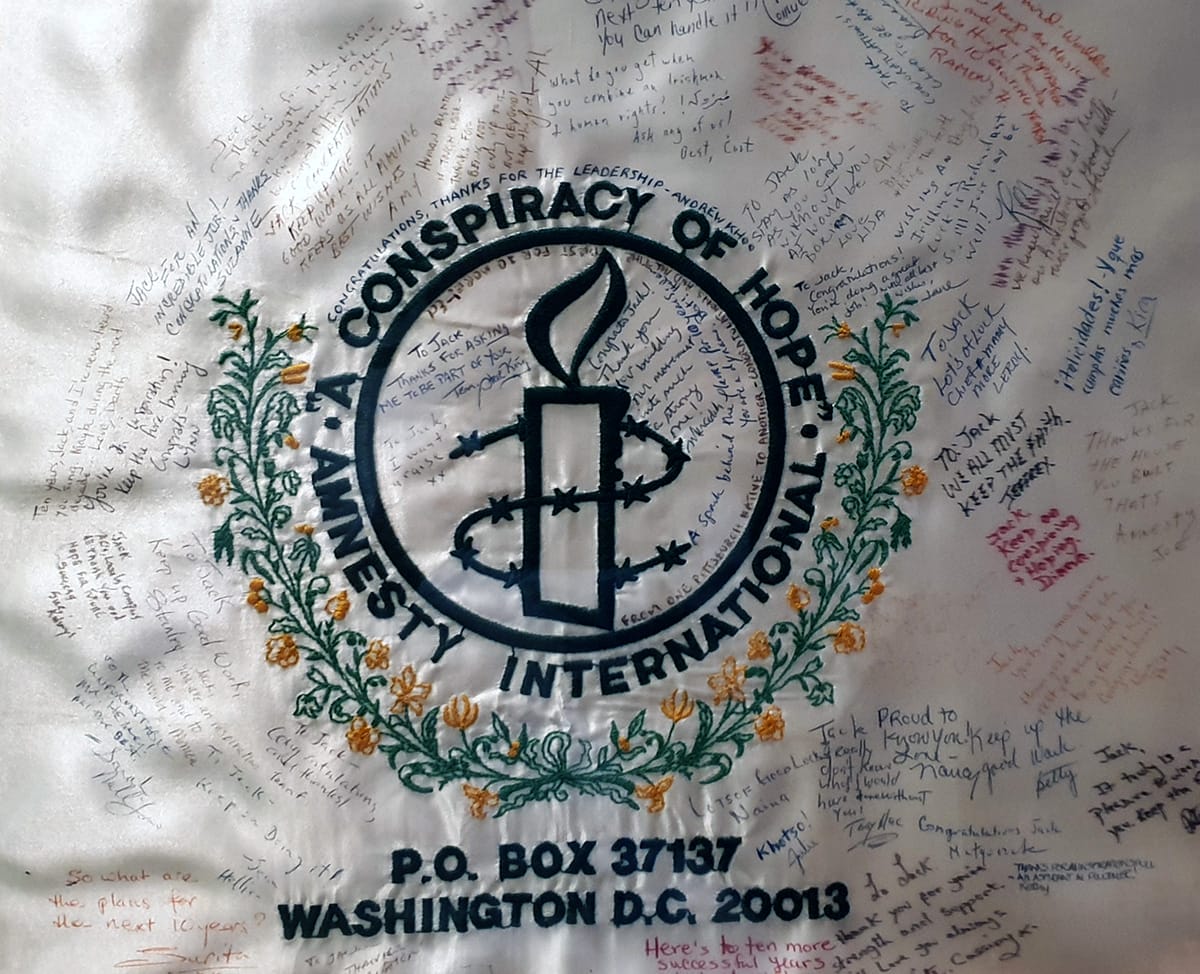

Autographed and embroidered Amnesty International poster on the wall of Jack’s basement reading room is a reminder of Jack’s contributions to grassroots human rights consciousness in the world of human rights lobbyists.

Hoisting the Amnesty International/USA banner “Conspiracy of Hope”, Jack organized these concerts in troubled regions of Latin and Central America including Chile immediately after the fall of US-patronized Pinochet dictatorship.

His efforts paid off.

Conspiracy of Hope closing on MTV, 1986. From left: Erin Neville, Joan Baez, Bono, Jack Healey (in Amnesty International tee shirt), Sting and Bryan Adams.

Human rights and music were on the cover of TIME magazine, that mass circulation news magazine which every American customer sees at the grocery store check-out counters. The popularity of human rights soared among youth populations on US campuses. Amnesty International/USA’s fee-paying membership base swelled to a couple of millions.

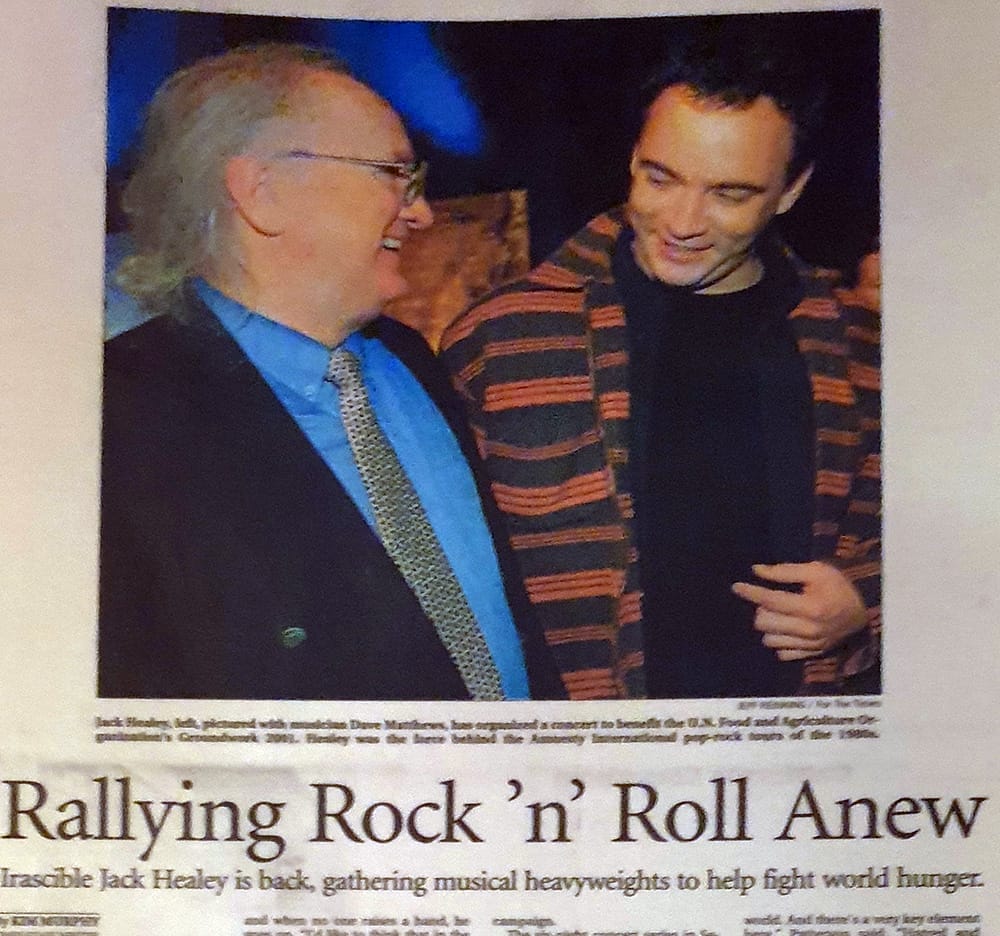

A newspaper clipping of Jack’s Amnesty music concerts. Here Jack is seen with the musician Dave Matthew of Dave Matthew Band.

When in January 1989 I started my foreign student life on the boringly flat campus of the University of California at Davis north of our flagship Berkeley, I joined Amnesty International and frequently attended the campus chapter’s meetings to receive instruction for the weekly letter writing campaign on behalf of AI-adopted prisoners of conscience around the world.

Membership in Amnesty was my sole membership in an organization that was built around university principles, beside the Burmese Student Association on campus. I still remember the pride I felt when in the post I received my membership card – really a rectangular piece of paper which one removed from the envelop and put in the wallet.

Little did I know that some 15 years later I would have the honour and privilege of becoming a very close friend and comrade of the man who put Amnesty International on the radar of the youth – through rock and pop.

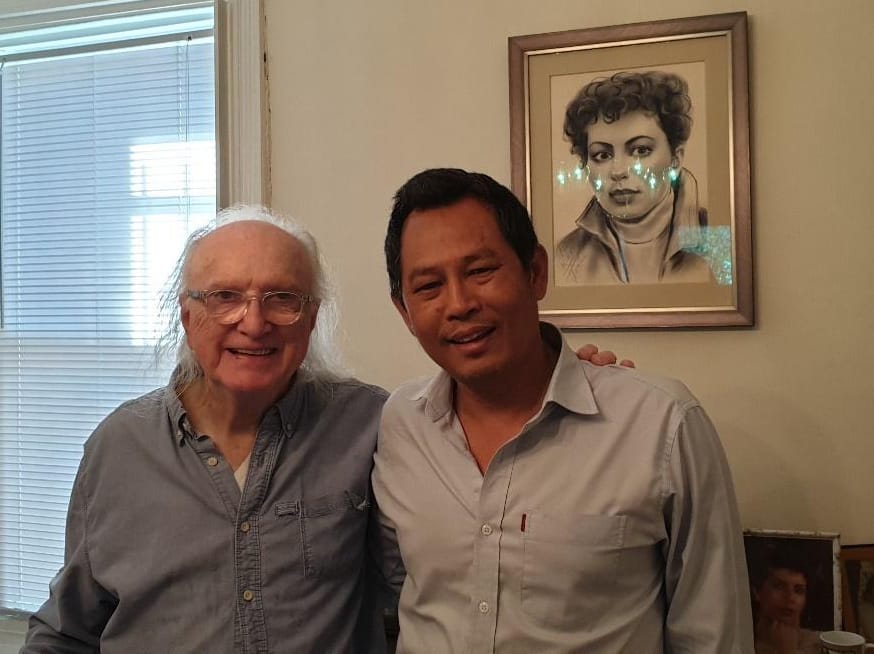

Jack and me, against the framed drawing of Jack’s late beloved Iranian wife. Washington DC, June 2019

For his contributions, Jack received several honorary doctorates.

The first time I visited Jack at his home near the US capitol and used the restroom, I noticed a framed picture of Jack receiving an honorary doctorate at a commencement ceremony, along with the huge credential in his name. Jack hanged the honour right above the toilet! I loved it.

That was the kind of irreverent man from whom I learned about the politics of human rights as it was known, pursued and advanced by the United States – and human rights circles, often too closely tied to the corridors of American imperialism.

As someone influenced by Liberation Theology, a radical – and accurate – reading of Christ’s message of standing with the poor and the oppressed – Jack knew more about Latin America, Africa and the Middle East than Asia, my continent or origin.

“Who’s Who” of exiled Burmese dissidents, including Dr Sein Win, Aung San Suu Kyi’s 1st cousin and head of the then exiled/opposition government based in Washington, DC. Jack (not in the photo) facilitated the retreat of exile. Harpers Ferry, West Virgina, February 1999.

Through me, he got to know many a Burmese political exiles and émigré. In the latter part of 1999 Jack travelled to Rangoon to deliver a message from us, a group of leading Burmese dissidents. Earlier that year, in Harpers’ Ferry, West Virginia, Jack and an American colleague of his with expertise on facilitating difficult conversations facilitated a 2-days retreat of leading Burmese dissidents who couldn’t find a common ground essential for building a unified front in exile. The place, to Jack – and those dedicated to a free humanity, signifies struggle for liberation where the leader of the armed Abolitionist movement in the United States John Brown staged his failed armed resurrection against slavery and was consequently hung.

Jack was a Peace Corps volunteer as a priest in Lesotho, Africa where he became good friends with the late Sandy Berger, who later became Bill Clinton’s National Security Adviser. Through his old friend, Jack arranged a meeting in the West Wing for me as a Burmese academic and Free Burma Coalition coordinator. He accompanied to the meeting with the Clinton White House including the head of National Security Team on Asia and Bill Clinton’s speechwriter. When the White House functionaries showed some readable signs of indifference on Myanmar regime’s egregious rights violations – despite their public denunciations – I ended up telling them to their face, “human lives not statistics nor collateral damage, you know”.

Jack was cool about it. He knew how I view Power, imperialist power at that. I see no humanity in any corridors of power.

Jack’s late wife was an Iranian émigré who practised human rights law in a DC firm. Naturally Jack took a deep interest in pervasive rights violations in the theocratic revolutionary Iran.

He knew the name of every single US official posted throughout Latin and Central America which the United States treated as its Cold War backyard. Washington’s sole interest in the other America of Spanish and Brazilian speakers was to install in power their anti-Communist “bastards” (for instance, Pinochet) to play wolves to the largely impoverished rural populations, who God forbid were demanding humane and equitable conditions of life.

The likes of Pinochet would be doing their American Masters’ bidding. That is, to flush out and destroy scholars, activists, journalists and priests who would side with the equality-demanding plebs of their societies.

On home front, in his previous incarnation as a Jesuit priest, Jack marched for the civil rights of the African Americans. Some of Jack’s civil rights era comrades were the likes of John Lewis, no less.

After he took the helms of Amnesty International/USA Jack saw through a fundamental error of choice by the then sole premier human rights organization in the world. He was a believer in the UDHR – that NGO jargon of Geneva for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He had this priestly oratorial knack for framing lawyerly discourses in ways that would speak to the average Joe.

In the 13-minutes interview I did with him in June 2019 at his home on C Street a short walk on the South side of US Capitol building, Jack simply put human rights as something “every mother would want for their children”.

Regarding human rights, you couldn’t be more eloquent, more powerful and more inalienable than that!

Jack with Nelson Mandela, Washington DC (circa. 1994)

One of Amnesty International’s fundamental errors of policy choice, as Jack rightly saw it, is the organization’s lenient – if at all – application of the universal human rights when it came to the United States and its Western vassal states of Western Europe. In those days, the Eastern Europe was the Soviet sphere. As he put it in the interview here western human rights campaigners focused almost exclusively on the violations of human rights perpetrated in the then Third World and the Eastern Bloc of the USSR while not holding the United States, to the same standards, in terms of the American conduct both at home and abroad.

It would have been hard to accuse Jack, a devout Catholic, as a Communist sympathizer or a Third Worldist. He was simply advancing the view that the universality of these rights enshrined in the UN document ought to be protected universally, whatever the population, whoever the perpetrators.

Still a student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where I was wrapping up my doctoral thesis on the Burmese dictatorship, I met Jack through my activist colleagues at American University where we had a very vibrant chapter of the Free Burma Coalition led by a very dynamic and capable undergraduate American student named Jeremy Woodrum, from Loveland, Colorado. The campus chaplain was named Joe Eldridge, who was a liberation theologian with an active involvement in the rights movements across Latin America.

In those days, Washington DC had a rather significant pool of Burmese political exiles, spanning two to three generations who opposed the military dictatorship in Burma since the early 1960’s. Aung San Suu Kyi’s first cousin Dr Sein Win, the university math tutor-cum-dissident in exile, was leading a parallel government, on her behalf, named the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB). Most of the Burmese dissidents were old-fashioned in their approach. They lobbied the US executive branch (that is, the White House and the State Department) and the Hill (or Senate and House of Representatives).

The Free Burma Coalition which I was running via Netscape and a listserv, out of my tiny $180 per month rental bedroom in Madison, Wisconsin, was taking the message of Burma divestment, corporate withdrawal boycott campaign – the present day BDS for Palestine – across high schools and university and college campuses. We were coordinating hunger strikes, direct actions, protest marches, acts of “mild sabotage” including wrecking Pepsi Cola vendor machines in university dining halls and other public spaces by simply putting chewed gum into the cash slots or simply leaving the machines un-plugged, or disrupting university regents’ board meetings.

When Jack and I met in Washington, DC, we hit it off. By then I had relocated from Madison to Washington to live with my then girlfriend, the environmentalist Annie Leonard (whom I later married and had a daughter with) upon finishing my doctorate in August 1998.

Jack saw in me a kindred spirit, a radical, with an analysis, not simply normative values which tend to be used elastically to advance a set of petty political interests.

For the next quarter century, our comradeship has remained intact, despite years of being out of touch with each other. Like a big brother, who has seen the world and done things I was just beginning to do, Jack held my hand, helped open doors in Washington, DC, counselled me on the typically dysfunctional politics of political diaspora and allowed me to use his 501(c) (3) registered NGO as conduit for fundraising. He would share fascinating first-hand accounts of his meetings with some of the most celebrated revolutionaries and human rights icon in Africa, some of whom he visited in apartheid regime’s prison including Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela, as well as Bishop Desmond Tutu.

The one difference we had for many years was over Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership. By 2004, I had already reached a conclusion that the iconic Burmese opposition leader was no Mandela of Asia, having failed to lead our opposition movement morally or intellectually. On his part, Jack continued to keep his faith in the woman whom he thought represented hope not just for the Burmese people, but for the global human rights movement which he was so organically a part for decades.

Whatever our differences, our loving camaraderie has remained intact, thankfully.

Jack Healy’s rights activism is truly radical simply because it is consistent with the universality of rights which rests on Jack’s level-headed analysis of US imperialism.

Both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have been guilty of applying international law rather elastically. In all previous genocides, they had stayed mum about the genocides, for instance, Rwandans, Uyghurs, and Rohingya, sticking to the unhelpfully narrow reading of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In the case of Rohingyas, Amnesty International could be said to have fuelled the Islamophobia and anti-Rohingya racism in Myanmar and Modi’s Hindutva India – as I have.

In sharp contrast, both organizations have made the genocide determination in the case of Gaza. It is not that I disagree with their genocide findings. Rather I’d wished both INGOs would have done the same for the genocide victims of Myanmar, Sudan and China.

Professor John Packer, the Canadian friend of mine who directs human rights centre at the University of Ottawa in Canada felt propelled to point out this intellectual and moral inconsistency of premier human rights organizations, in this case, the Human Rights Watch. The absence of a real anti-imperialist analytical framework – which had pained my old friend Jack very much – and the absence of moral consistency, I will argue, the ideals and application of human rights as a basic organizing principle of post-World War II era.

In the world where human rights NGOs tiptoe around the issues their funders don’t want them to touch, or assign relative degrees of victims’ worth, or of criminality of the perpetrating states, I miss my old friend Jack Healey. Now in his late 80’s, Jack is no longer as active or involved as he used to be.

Whoever pays the piper chooses the tune! But Jack sings his own tune of uncompromisingly universal human rights in that dirty swamp of Imperialist Washington.

I am just glad that I paid him a visit at his DC home in June 2019 and recorded his critique of what is wrong with western approaches to human rights. When I saw he was slowly recovering from some illness. I wanted to be considerate, and hence a shorter interview than I would like to. Jack has lived an extraordinary life as a devoted rights activist and has so many stories to tell and insights to pass on.

“How prescient Jack was,” I thought, upon watching Jack dissect the Washington-centred politics of human rights in mere 13 minutes!

Maung Zarni