Dr Nyi Nyi, the architect and implementer of the widely unpopular “New System Education” (or Sa Nit Thit Pyin Nya Yay) during the first decade of General Ne Win’s socialist military dictatorship, died in New York. He was 91.

The British-educated geology professor from Rangoon University was the most influential civilian in the otherwise entirely military cabinet, in the area of the RC’s educational policies. His meteoric rise to the commanding heights in Burma’s education in the early decade of General Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council (RC) was a talk of the nation.

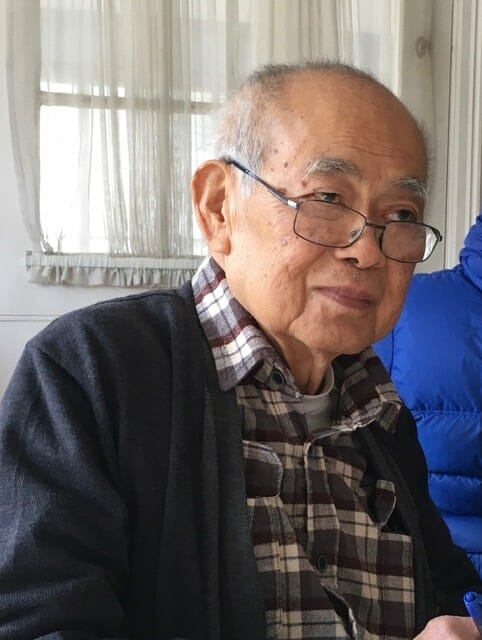

Photo credit:Irrawaddy News Group, 10 December 2021

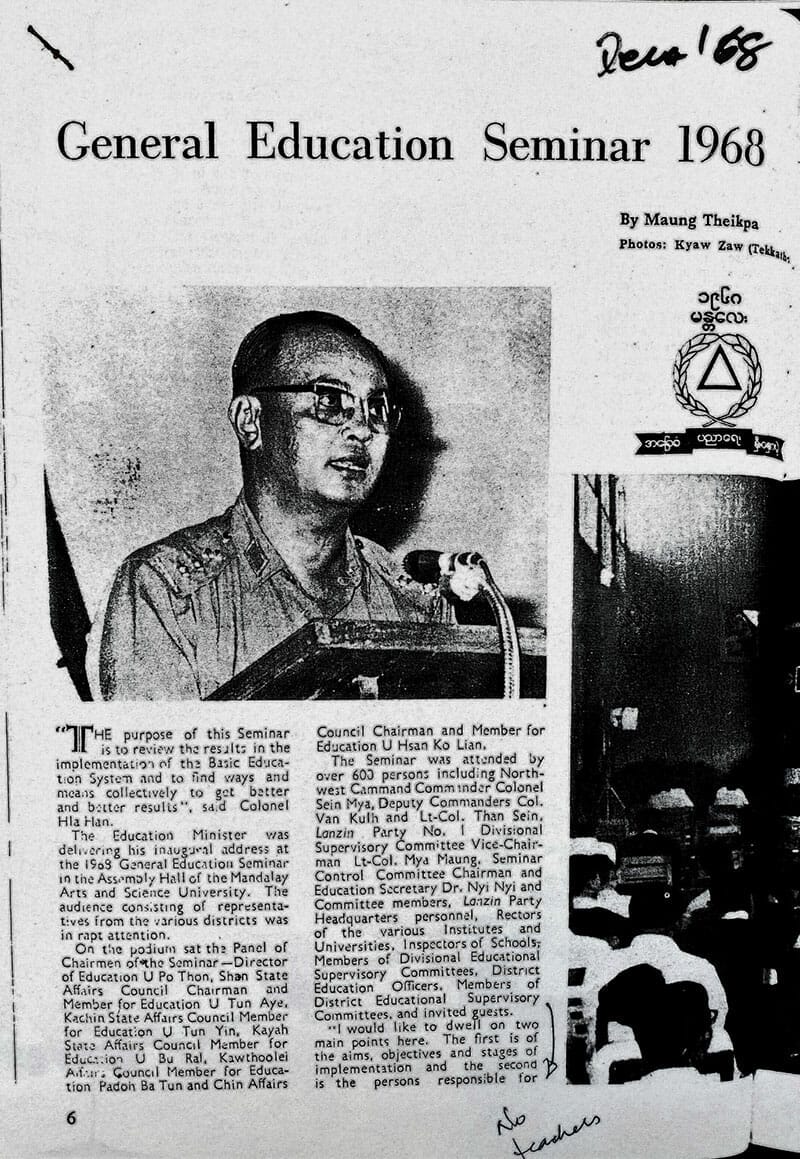

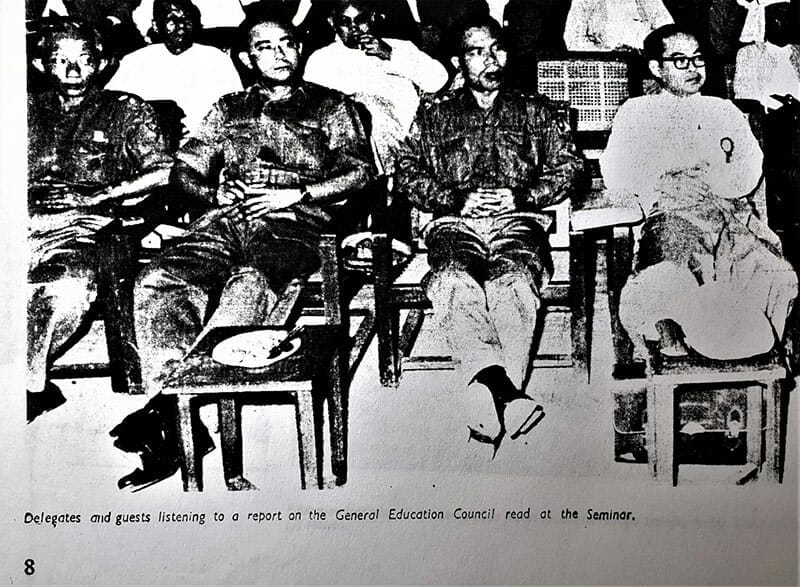

Bespectacled Dr Nyi Nyi, Education Secretary and Chairman of the General Education Seminar Control Committee, seen with his boss Colonel Hla Han, Education Minister and a member of the Revolutionary Council, Mandalay University, 1968

I grew up hearing his name from my educator mother, who, as a cock in the vast state education machine, had to execute Dr Nyi Nti’s New System Education. I was also processed through this “socialist education” system where we students were to be future cadres armed with technocratic knowledge to build a Socialist Utopia of “heaven on earth.”

Dr Nyi Nyi (1930-2021)

Professor of Geology, Deputy Minister of Education and Minister of Mines, the Union of Socialist Republic of Burma (Photo Credit: Irrawaddy News Group)

For a little over a decade, Dr Nyi Nyi served first as Deputy-Minister of Education (from 1965-1974) and subsequently, as Minister of Mines in General Ne Win’s cabinet (1974-75).

When TIME magazine “discovered” Nyi Nyi, a rare civilian who held a ministerial post in Ne Win’s military-dominated cabinet holding the important portfolio of Mines in a resource-rich Union of the Socialist Republic of Burma and painted him as a future leader it was too much for the anti-West and xenophobic dictator. It was widely rumoured that Ne Win removed Dr Nyi Nyi from his ministerial post on the excuse of the latter being of “Chinese blood”, and shipped the latter out to Canberra as Burma’s ambassador to Australia.

It was a rather curious excuse if only because the late dictator Ne Win was a Sino-Burmese himself, which was public knowledge. Besides, several top deputies in his coup regime were of similar Sino-Burmese or “pure” Chinese background, for instance, Brigadier Aung Gyi, Ne Win’s 2nd in command, and Colonel Tan Yu Hsaing.

When we met in New York City in the fall of 1994, Dr Nyi Nyi told me, “U Ne Win himself was Chinese. I saw him at his residence in his shorts. His thighs are so pale (like Chinese complexion)”.

As a matter of fact, Ne Win knew Nyi Nyi’s older brother – Yin Pe – who served as a sergeant in the Burma Rifle Regiment Number Four under the commandership of the then very senior Colonel Ne Win in the early years of the Burma Armed Forces (founded under Fascist Japan’s patronage in 1942).

“Family background and ties mattered to him” (General Ne Win), Saya Nyi Nyi said.

Post-Ambassadorship, Dr Nyi Nyi sought and found employment abroad, and landed a senior executive position with the United Nations Children Education Fund at its New York Headquarters. When I met him for the interview in New York City Dr Nyi Nyi was Advisor the Executive Director of UNICEF at the headquarters.

Civil-Military Symbiosis: “No, I don’t feel I was used or manipulated by the Revolutionary Council.”

It has long been a standard feudalistic or neo-totalitarian practice among the Burmese to either credit or blame it on One Big Leader, for anything that transpires, good or evil.

A case in point.

In the Burmese language obituary (dated 10 December) in Irrawaddy News Group website, the well-known educator and writer U Than Oo was quoted as saying, “Dr Nyi Nyi was not responsible for the failure of the new education, but General Ne Win was. He (Nyi Nyi) did not have the power to enact 1964 Universities Act (which broke up the two national universities – the University of Rangoon and the University of Mandalay). “ (See https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/2021/12/10/247999.html)

Photo credit: BBC Burmese (Dr Nyi Nyi is the third from the left, sandwiched between Rangoon University Rector and geology professor Dr Tha Hla – to his right ¬ and another geology professor U Ba Than Haque to his left)

In a more in-depth analysis Bobo Lansin of BBC Burmese raises the question whether Dr Nyi Nyi was simply the victim of strategic manipulation by the military rulers, or the real player with power or “the guilty party” in the emerging educational reforms ushered in by the military’s Revolutionary Council.

But both interpretations run counter to Dr Nyi Nyi’s own critical reflection on his educational leadership, the extent of his say in educational matters, and the policy space that existed in the civil-military relations in the early formative days of General Ne Win’s one-party military rule of 1960’s.

The military-controlled Burma Socialist Programme Party publication, “Party Affairs,” (Issue #10, Oct, 1969) spelled out the role of technocratic experts and intelligentsia, in building the (military’s) socialist republic.

In the Soviet era, a term “Stalin’s idiots” emerged in specific reference to the experts (or technocrats and intellectuals) who were anointed policy advisers and implementers in Josef Stalin’s ruling circle. Perhaps the Burmese slang that roughly captures the essence of the Soviet phenomenon – would be Anar Pya Gyi or sycophant.

Between 1990 and 1995, I interviewed over 100 Burmese emigres in the United States including university-educated members of General Ne Win’s coup regime known as the Revolutionary Council and prominent Burmese academics who also were friends or well-acquainted with dictator Ne Win.

When it came to educational affairs no civilian had greater influence over the structure, the mission and policy priorities of Burmese education, both pre-collegiate and university education, than Dr Nyi Nyi, in spite of his lack of specialized expertise in educational policies, administration, reforms or curriculum and instructions.

The late Professor Than Tun, the preeminent historian of Burma, and former leftist student activist comrade of Dr Nyi Nyi, who refused to play along with General Ne Win’s socialist state building.

Dr Nyi Nyi was “a specialist in rocks” as his contemporary and fellow leftist student activist Dr Than Tun, the late preeminent Burmese historian was known to have openly told his friend and socialist educator, implying that the latter should mind his business of studying rocks as opposing to playing the socialist educational reformer! Dr Chit Swe, the rector or vice chancellor of Rangoon University and head of the Computer Science Studies Center on campus at the time of the 1988 uprisings, did not speak favourably of Dr Nyi Nyi, when I interviewed him in Illinois the same year (1994). “Ko Nyi Nyi was an ambitious climber who was doing politics even amongst us ‘Burmese state scholars’ in London, hosting small dinner parties at his place,” said Chit Swe. He was a contemporary of Nyi Nyi in London where he did his PhD in maths at the University of London while Nyi Nyi was doing his PhD in geology at Imperial College, London.

One retired head-teacher (or principal), who wishes not to be named, now in her early 90’s from Mandalay, said something along the lines of Dr Nyi Nyi, making an advance at her and then telling colleagues that she had a thing for him. She met and knew Dr Nyi Nyi when he was crisscrossing the country to canvas teachers’ opinions about the socialist reforms that he was spearheading under the military’s Revolutionary Council from 1965-1974.

Perhaps most memorable tale I had collected of the social educator was the following.

Retired NHS Consultant and medicine professor Dr Khin Maung Myint in London, himself a Rangoon University-faculty-bred who grew up on campus, recounted to me a rather hilarious story. In the middle of a meeting at Rangoon University, former Rector Dr Tha Hla, whom Dr Nyi Nyi called “the father of geology as an academic discipline in Burma”, walked out, having mooned Dr Nyi Nyi, the latter’s pupil who served the Revolutionary Council as the architect of the social education reforms. Professor Tha Hla was known to be a no-nonsensical and foul-mouthed teacher among his students, by Dr Nyi Nyi’s own account.

Although I don’t quite remember the details that triggered the good old rector deliberately dropping his male garment – known in Burmese as Pa-hsoe – as a dramatic act of expressing his disagreement or disdain he had for his former pupil.

When I asked him about his leadership style – whether the community of fellow educators and academics dared to critique his new policies or criticize him for his leadership in the progressively dictatorial political context where criticisms were not welcome – he said quite frankly, “A lot of fellow academics and other colleagues did feel comfortable expressing their opinions about me and my work.”

Quite.

Dr Nyi Nyi, The Architect of the Socialist or New Era Education

In the fall of 1994, I interviewed Dr Nyi Nyi in his UNICEF office in New York City for my PhD thesis on the politics and policy-making in education in Burma under General Ne Win’s one-party military rule. Specifically, I asked him if he felt the military leadership just simply manipulated him into doing their bidding of control over knowledge and all aspects of schooling, from kinder garden to post-graduate level university education.

When I sifted through my written notes and 3-hrs of audiotaped interview with Dr Nyi Nyi, the geology professor in his prime years turned out to be a classic case wherein members of ambitious members of civilian intelligentsia, that is, experts, academics, researchers, technocrats etc., in Burma – and perhaps universally – seek various forms of symbioses with those with political (and economic) power.

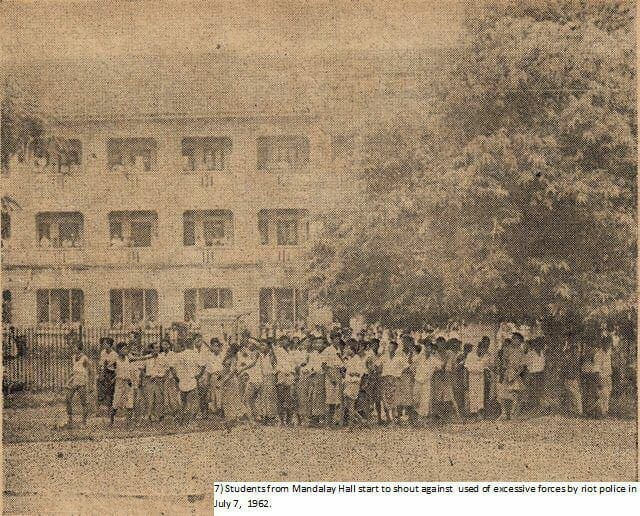

Rangoon University students held a protest rally against General Ne Win’s military coup of 2 March 1962, which violently ended Burma’s parliamentary democracy practised since independence from Britain on 4 January 1948.

Some months after the infamous slaughter of anti-coup student activists and dynamiting of the historic Student Union building on Rangoon University campus on 7 July 1962, Dr Nyi Nyi went to see his old classmate and friend from the Irrawaddy Delta town called Myaung Mya.

In Nyi Nyi’s words, “I went to see my old classmate and friend Major Maung Maung Than Tun (Navy) at the Old Secretariat (where the cabinet offices of the Revolutionary Council were located). “

Addressing his friend by his old civilian name, Dr Nyi Nyi continued, “Ko Than Tun was a Special-Officer-on- Duty seconded to the Education Department in the Revolutionary Council. After we had chatted for a bit he asked me to meet his boss Colonel Hla Han, then in-charge of the country’s Education.”

Colonel Hla Han, a member of Gen. Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council (the coup junta), and “Education-In-Charge”, address the General Education Seminar, Mandalay University, 1968, organized by Dr Nyi Nyi, as Chair of the Seminar Control Committee.

In those days, there were very few military officers with university education, and the Education department was headed by two military doctors – Colonel Hla Han and Colonel Maung Lwin, according to Dr Nyi Nyi.

Dr Nyi Nyi stressed that the military officers whom he met solicited his advice as to how best to handle anti-military political activism on university campuses.

“They (the military leadership) realized they did not know how to handle education (and campus activism), and they said to me, “Saya, we are so glad you came to see us. Can you give us some strategic advice on how to reopen universities. It is not good for our country for us to close down universities because of campus activism.”

Subsequently, Dr Nyi Nyi submitted to the Education Department run by a group of military officers under Colonel and Dr Hla Han, Director of Medical Services at the Ministry of Defence, one specifically advocating the break-up of two national universities – universities of Rangoon and Mandalay – in order to directly address the issue of campus student activism, including student union activities, and the other, aimed at turning the academic curricula in schools and universities into instruments of linguistic and cultural nationalism of the dominant Bama ethnic group.

Additionally, in the curricular and admissions reforms Nyi Nyi was categorically for denying students who were not full-citizens of the country educational access to science, technology and other fields deemed crucial for building a modern developmental state, namely medicine, engineering, agricultural, veterinary and industrial or applied sciences.

Dr Nyi Nyi offered me elaboration justification for his use of nationality as the sole criterion for admissions into these academic and professional fields deemed crucial for “nation-building”.

In our interview, Dr Nyi Nyi justified linguistic nationalism which placed the emphasis on the teaching of Burmese language as the sole medium of instruction on the basis of the then emerging research findings from applied linguistics. He said, “children who are taught through their mother tongue as the main medium of instruction do better.” This view seems to be supported by the prevailing educational research.

Four Objectives/Responsibilities of students in the socialist education or New System Education (the 10th anniversary assessment), Myawaddy magazine, Ministry of Defence Department of Psychological Warfare (or Public Relations), 1975

Establishment Intellectuals or Stalin’s Idiots?

On making policy-decisions, Dr Nyi Nyi said, “I didn’t need to get any direct greenlight from General Ne Win in these curricular matters as he was preoccupied with other issues such as politics, economy, etc.” Nyi Nyi said, “the military officers, most of whom did not have proper university – and for some, not even high school education – in those days had undue respect and appreciation for PhDs. So, I had a lot of free reins in educational reforms.” He continued, “but I did need some kind of overall clearance for my language of instruction reforms.”

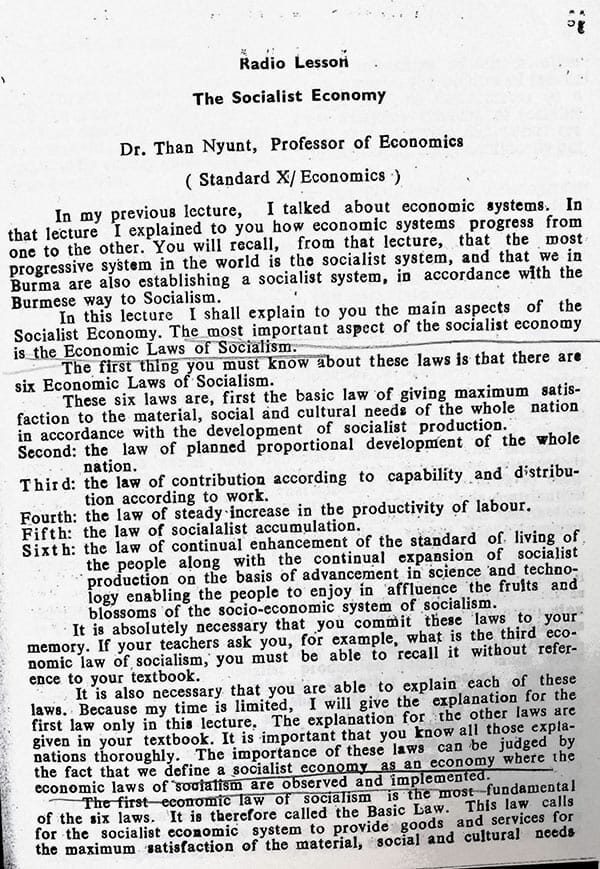

An English language transcript of a high school level radio lesson on socialist economy by a Western-educated Burmese economist Dr Than Nyunt, republished in the Light of Education, V. 36, #8, Aug. 1987, Ministry of Education (one year before the military’s Burma Socialist Programme Party collapsed).

He stressed that making Burmese as the sole medium of instruction in all levels of education, except at the Master’s level courses was very much in line with the ethos and popular demands for use of “Burmese as our official and national language”, rooted in the anti-colonial nationalist days of “We the Burmese Association” which produced most of the country’s national leaders. He also offered Thailand and Japan as two countries with successful policies of native-language medium of instruction and argued that egalitarian ethos of expansion of educational access vis-à-vis the elitist education for the few, a colonial hold-over, was a key factor in developing the New System (Socialist) Education.

He then hastened to add, “in the later years the military leaders could only think of how to instrumentalize credentialed civilians and technocrats.” After nearly 60-years in near-monopoly power, the military officers as a ruling class of Burma have come to master the art of turning otherwise well-meaning western educated PhDs and others with advanced degrees from US Ivy League schools and Oxbridge of Britain into textbook Stalin’s idiots.

Those who clustered around Myanmar Peace Center during the top-down democracy reform years of President Thein Sein – 2010 to 2015 –, fit the profile.

Among them – in order of prominence – are historian and writer Thant Myint-U; medical-doctor-cum-Presidential-speech-writer and Yale Global Fellow, the Dr Nay Win Maung; Cambridge-trained geologist, and former daughter-in-law of the late General Ne Win Dr Yin Yin Nwe; Cornell-educated political scientist Dr Kyaw Yin Hlaing who served as Thein Sein regime’s main policy defender of Rohingya genocide; former student rebel and Georgetown-trained Dr Min Zaw Oo; development technocrat Zaw Oo who studied at Columbia University and American University, and veteran student rebels Aung Naing Oo and Aung Thu Nyein who did their MPA degrees at Harvard Kennedy School.

These western-educated Burmese may have been Stalin’s idiots, but they were expensive idiots, nonetheless. Each of them was reportedly drawing US$10,000.00 per month salaries from the civilian government headed by ex-General Thein Sein, which in turn received “donor peace funds”. Compare those advisers’ salaries to average income of the majority of people who live on $5 a day.

At $10,000.00 per month who in their right mind would not prefer “peace” to the People’s Revolution and Resistance?

These men and women continue to either stick with their own contacts and “friends” in the military under the coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing, or advocate peace and negotiations in the deepening revolutionary and violent politics of today, dismissing Generation Z who have become a powerful pillar of the People’s Revolution which combine non-violence Civil Disobedience Movement (hollowing out the military-controlled state bureaucracy) and the armed militia movements across the country.

Socialist Ethos and Linguistic Nationalism of the New Education System or Socialist Education

Returning to Dr Nyi Nyi’s Burmese-only instructional language policies, what I found problematic was his categorical dismissal of teaching of English as a Foreign Language in Burma as “utterly futile and ineffectual”.

A veteran student activist with left-wing Progressive Front, which dominated campus political activism across the country, Dr Nyi Nyi was at ease borrowing slogans from Maoist China. He propagated the Maoist view, it is not enough to be expert at something to be of value to the post-colonial Burma, one has to be both “red and expert”.

Dr Nyi Nyi, the Person

Dr Nyi Nyi, in his retirement in New York, Photo: Irrawaddy News Group

As the Burmese saying goes one doesn’t make a final assessment of others, morally or otherwise, until they have exited our world. People change, and they change constantly. Ex-criminal convicts repent and rehabilitate themselves while Nobel Peace laureates (for instance, Aung San Suu Kyi and Abiy Ahmed Ali of Ethiopia) turn genocidal or criminalistic, to offer two examples of the good and the evil on a single moral continuum.

Now that Saya (or teacher) is no more, I feel it justified to make some conclusive remarks about Dr Nyi Nyi, the person and Dr Nyi Nyi, the intellectual in a symbiosis with the military dictatorship.

Dr Nyi Nyi, (with spectacles seated in the front row), the lone civilian technocrat, among military deputies in General Ne Win’s 1962 military junta, The General Education Seminar, Mandalay University, 1968.

I am writing these words not so much as an obituary of a public figure who helped laid the educational foundation for Burma’s military-controlled politico-economic system but as a tale which offers some invaluable lessons for the western-educated elite, who self-perceive themselves as advisers, policy actors and power brokers in the government of the day.

Saya (or teacher) was neither a victim manipulated into doing the military’s bidding in education nor the guilty party who destroyed Myanmar’s mass education system. After all, neither Myanmar society and culture nor successive systems of education have fostered any development of critical intellect or the so-called critical thinking, be it in the pre-colonial feudal days of heavy rote-learning, the alien British colonial days during which colonial university education with English as the medium of instruction was about the staffing need of the Empire.

As a person, Dr Nyi Nyi was short and diminutive even for a Burmese. He was warm and welcoming. To my pleasant surprise, he was even respectful and appreciative towards a youngish scholar who sought out his vast knowledge of Burmese education. He was self-made educator and educational reforms, despite lacking former training in educational reforms or administration.

He was focused and sharp, and instantly picked up on the fact that I wasn’t impressed with the bareness of his office – a big metal desk and a cheap commercially produced poster of the ancient city of Burma called Bagan on the wall – in his post-ministerial UNICEF job.

“You know Saya Gyi’s position here is high up,” he blurted out to assure me that he still was an important person. I said, “Yes”, nodding with a mix of respect and sadness. For his office betrayed no prestige or high status nor the old glories of him as the architect of the Social Educational Reforms.

We said down one-on-one for a tape-recorded interview for the next several hours. As our interview winded down and the lunch hour approached Saya asked me, “let’s go get a bite to eat”.

Whatever our views and judgments about individual Burmese who have tried to use their education, talents, energy and skills, through some form of cooperation or collaboration – principled or simply self-interest-driven – one thing has emerged crystal clear (to me).

Successive generations of intellectuals of post-colonial Burma have failed the country, by any yardsticks. That is a sad but irrefutable conclusion, I have drawn from my 30-odd-years of trying to be of service to the cause larger than my own academic career. Saya Nyi Nyi’s life was no different from other lesser mortals.

Some years after the failed 8.8.88 People Power uprisings in 1988, John Badgley, the now-elderly American scholar of Burmese politics and an old friend of mine from Ithaca, New York, met up with the late Dr Maung Maung, on the steps of Universities Library in Rangoon. Educated at Netherlands’ Utrecht University and Lincoln’s Inn of London, UK, Maung Maung was the only military-appointed civilian president in dictator General Ne Win’s inner circle where he served as Ne Win’s sole legal adviser.

In the last several weeks of the 1988 nationwide uprisings against Ne Win’s failed one-party dictatorship, Maung Maung was made President of the Union of the Socialist Republic of Burma. He lasted less than 30-days as the younger generation military officers led by Ne Win’s intelligence chief Colonel Khin Nyunt secured greenlight from the aging dictator Ne Win to remove any civilian façade of the military rule and took over the rein of the failing state engulfed in the nationwide protests from Dr Maung Maung.

“We (the Burmese liberals) have failed Burma,” were among the last words Maung Maung said to our mutual American friend Dr Badgley, with the benefit of the hindsight.

Indeed.

Maung Zarni