I woke up to a small group email from Denis Gray, Chiang Mai-based, former chief of Associated Press Bangkok Bureau with “Josef Silverstein” in the subject line. I knew immediately the email carried the sad news. Several other group emails from others also awaited in my inbox, which carried the same fact, laced in different words: Joe passed away in his home in Guilford, Connecticut, on the morning of June 29th.

It is sad news for those of us in the Burma world who had known Joe as a fixture for a long time.

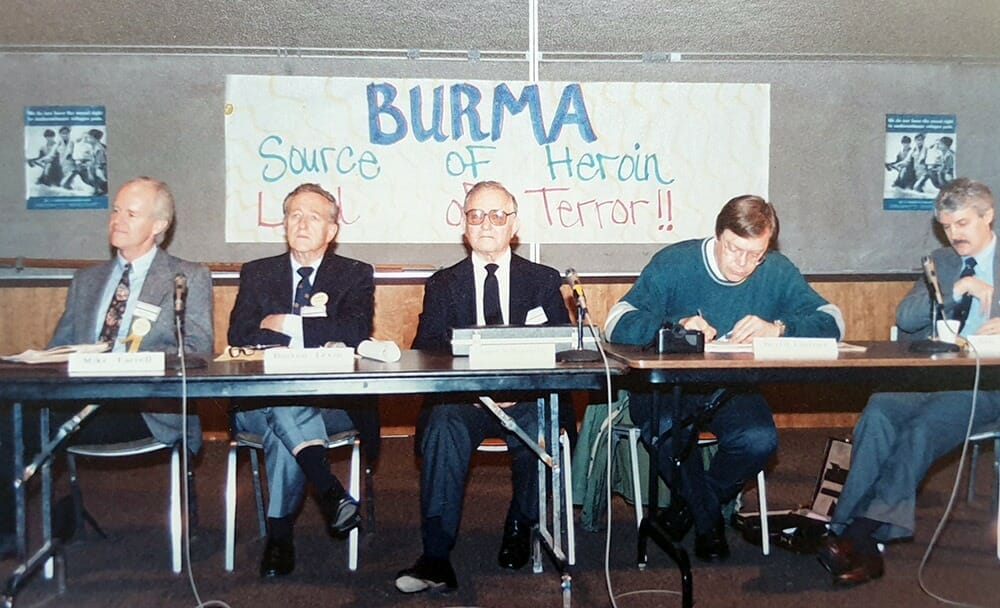

Josef Silverstein at the Burma Forum at Golden West College, Los Angeles, 1991

Josef Silverstein, Professor Emeritus of International Relations and Southeast Asian Studies at Rutgers University, was no run-of-the-mill Western expert or academic doing Burma – or now Myanmar. Contemporary with the likes of the late Benedict R. O’G. Anderson who specialized in Indonesia studies, Joe was part of the breed of international scholars who, like Anderson, chose to forgo access to the countries and peoples they studied – and cared about – as they endured under murderous military dictatorships. Joe used his scholarship and public voice as an intellectual to speak out against the emerging political repression – at the expense of an entry visa to the country, now under a regime hostile to academic truth-seekers.

Scholars like Anderson and Silverstein were typically on the persona non grata lists of these emerging dictatorships in Southeast Asia.

Unlike the US-allied Indonesia, during the dark decades of Suharto’s misrule (1965–1997), General Ne Win’s Burma was cut off, literally, from the outside world of cultures, academia, international markets, and travel for a quarter of century since the textbook coup of 1962. Only a handful of western scholars of Burma, who had a chance to actually live and carry out any country-study in the preceding years of Ne Win’s coup (1962).

US President Lydon B. Johnson and the First Lady welcoming Burmese dictator General Ne Win and wife Kitty Ba-Than at the White House, Sept. 1966.

Joe was one of that handful who got to know the people and the country living in my hometown of Mandalay. Just a year prior to the coup, Joe lived, researched, and taught at the University of Mandalay, my alma mater, as Fulbright Lecturer. He started his academic career at an all-women’s liberal arts college, Wesley, in Massachusetts prior to coming to my town and ended up spending his entire academic career as professor of southeast Asian Studies and International Relations, at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

I was not born then, and my late mother was in her Intermediate B years (junior and senior years) and was studying with Joe’s Burmese colleague, the late Maung Maung Gyi, Yale-trained political scientist running both history and political science departments and author of Burmese Political Values. The Socio-Political Roots of Authoritarianism.

I am sure my late mother must have attended Joe’s lectures in those days, although I never specifically asked her if she had Joe as her lecturer. In those pre-military days academic freedoms were a given, and universities were run by autonomous bodies of scholars and administrators in Burma.

In those Cold War days, the United States government was pouring in hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars to deepen the knowledge base of strategic regions and countries with communist resistance, both above and underground, such as Burma. Recruiting western scholars in so-called area studies, to serve as eyes and ears for the Central Intelligence Agency while endorsing the pseudo-scholarly paradigm of (anti-communist) soldiers as capable “modernizers” whose class alone could break free of their countries’ chains of (“backward”) “traditions” and pursued (capitalist) development.

The usurper, General Ne Win, was feted on a state visit to Washington DC in September 1966, by President Lyndon B. Johnson, as “an ally” of USA in the fight against evil Communists, while Washington viewed the ousted democratic PM, U Nu, as weak in this fight. U Nu attempted Leftist Unity as a peaceable path to the country’s post-independence conflicts as the Communist rebellion kicked off “multi-coloured” rebellions, by Communists of different shades of red.

Un-perturbed by the Communist fear mongering, Joe remained a clear-eyed scholar who saw inter-ethnic strife as a key obstacle to nation-building. He saw organic ethnic unity as a solution to Burma’s woes. For different ethnic nations were compelled to be straight-jacketed into a centralized, unitary, Bama-controlled ethnocratic state, where the ethnic majority were more equal than the rest of the “little” ethnic brethren such as the Shan, the Karen, the Mon and so on.

Banned from Burma by Ne Win’s regime, Joe travelled to Eastern Burma – bordering with Thailand – under the military and administrative control of the Karen Nation Union/Karen National Liberation Army, learned about national minorities’ aspirations and grievances, and published Burmese Politics: The Dilemma of national Unity (Rutgers University Press).

Banned from Burma by Ne Win’s regime, Joe travelled to Eastern Burma – bordering with Thailand – under the military and administrative control of the Karen Nation Union/Karen National Liberation Army, learned about national minorities’ aspirations and grievances, and published Burmese Politics: The Dilemma of national Unity (Rutgers University Press).

Based at Rutgers University, Joe lent his authoritative voice to the efforts of the growing number of Burmese political exiles and dissidents in diaspora and travelled to speak at activist public events (protests or policy discussions?) while delivering guest academic lectures across various Southeast Asian Centres and reading his scholarly papers at the Association of Asian Studies. Before the days of the rise of political and human rights INGOs in the United States and elsewhere, Joe supported the then influential exiled dissident organization, the Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in Burma (CRDB), with chapters in several major democratic countries, founded in USA by a group of prominent exiled Burmese dissidents in 1986.

He took a keen interest in the intellectual and ideological vision of the Marxist-inspired revolutionary and founder of the Burmese Army, the martyred Aung San. His research resulted in the monograph entitled The Political Legacy of Aung San (Cornell University Press). Joe understood Aung San’s less-than-rigorous grasp of the ideas of politics and nation-building. Still, he appreciated Aung San’s enormous legacy in Burmese national politics, and pinned his hope on his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, as she emerged following the country’s 8 August 1988 (or 8.8.88) nationwide uprising as the credible challenger to General Ne Win and “my father’s military”, as Suu Kyi was fond of saying.

Portrait of Ne Win, a military commander who served as Prime Minister and President of Burma. Ne Win was Burma’s military dictator during the Socialist Burma period of 1962 to 1988. Wikipedia Commons

Despite his passionate support of Burmese people’s struggle for the restoration of democracy and freedom – human rights, was not a buzz word then – Joe maintained his clarity in his scholarship. Denis Gray, who covered Burma from Bangkok and had known Joe since 1970’s wrote, “I still remember how he saved my professional rear end, when in 1988 several news outlets were reporting that it looked as if the pro-democracy movement would gain the upper hand, based on the fact that some civil servants and even soldiers were joining its side. He cautioned me with a remark like, ‘The military hasn’t cracked. It is still holding the fortress.’ We held back, and sadly Josef proved right.” that

Denis Gray was not the only one who held Silverstein’s clear-eyed scholarship rested on his professional integrity. The late Lou Walinsky, who served as the economic adviser to the Government of Burma, and lived in Burma in that capacity from 1953-58 and the author of Economic Development of Burma (1951-1960), said to me, on more than one occasion, Joe Silverstein was a strong scholar and a staunch advocate for Burma’s freedom from dictatorship, vis-à-vis the rest of American scholars, who typically, parroted the Burmese military’s state-centric narratives.

Joe testified on Burma’s political repression before US Congressional committees joined protest rallies against US’s pro-military policies towards Burma.

A scholar with integrity, he loathed fellow Burma scholars who would kowtow to the Burmese dictatorship in exchange for access to the country (that is, entry visa and research permits). A cursory glance at Joe’s publications will tell of Joe’s uncompromising democratic principles which guided his scholarship.

A year before the Ne Win dictatorship collapsed amidst mass protests, political pressure from Japan, (the patron-donor of the military-ruled Burma), and economic ruins – with barely $25 million in Burma’s foreign reserve coffer, the Association of Asia Studies held its annual conference in San Francisco in 1987. At the AAS Conference, Michael Aung-Twin, the American-trained Burmese historian presented his myopically nationalistic and pro-coup spin disguised as “scholarship” in a paper entitled “1948 and the Myth of Independence”. He argued that Burma only regained its complete independence from Britain only in 1962, when General Ne Win staged the coup, dismantled the parliament, dissolved the country’s constitution, closed the society off the Western-dominated world in order to ward off all the un-Burmese influences and reclaimed complete sovereignty from the colonialist West. In attendance, Joe was said to have been livid.

Thirty-years ago, I met Joe at a dissident’s forum in 1991 organized by a mutual Burmese friend, U Kyaw Win, professor of counselling psychology at Orange Coast College and the founding chair of the CRDB. Joe spoke alongside journalist Bertil Lintner, former US Ambassador to Burma, Burton Levin, who blew the whistle on the Burmese military’s bloody slaughter of unarmed and peaceful civilian protesters in 1988, and Eric Sandberg of the US State Department Southeast Asia Affairs section.

Thirty-years ago, I met Joe at a dissident’s forum in 1991 organized by a mutual Burmese friend, U Kyaw Win, professor of counselling psychology at Orange Coast College and the founding chair of the CRDB. Joe spoke alongside journalist Bertil Lintner, former US Ambassador to Burma, Burton Levin, who blew the whistle on the Burmese military’s bloody slaughter of unarmed and peaceful civilian protesters in 1988, and Eric Sandberg of the US State Department Southeast Asia Affairs section.

See bespectacled Josef Silverstein at the centre of the panel, at the Burma Forum at Golden West College, Los Angeles, 1991

Almost decade later in May 1999, Joe and I travelled to the Hague to speak at the Hague Appeal for Peace, “an end of the century, civil society conference”. We shared a panel talking about prospects for peace in Burma.

In the subsequent decades, I lost touch with Joe, and heard from grapevine that Joe felt optimistic about the “fragile democratic transition” with Aung San Suu Kyi at the helm in 2016. To his credit, however, Joe remained sharp as a Burma watcher. He told Thomas Fuller of New York Times in 2013, “to the outside world, nothing has really changed with her; she is Suu Kyi and all the beautiful things that go with it. She is essentially making herself irrelevant. We have not heard Suu Kyi talk as Suu Kyi.” He was concerned about Suu Kyi staying silent while her father’s army broke ceasefire with the Kachin Independence Organization and resumed vicious military operations against Kachin ethnic minority in the north.

How pained and disappointed he would be by daily Myanmar updates now! All news from Myanmar today is bad news!

As a young émigré Burmese student studying my own country’s affairs, I found Joe’s objective scholarship extremely valuable. He knew and learned from many best-informed Burmese political figures in exile or in diaspora, and kept his scholarship alive, despite no direct access to the country during the dictatorship years.

Joe, the person, was nurturing of Burmese students who were doing their advanced studies in US universities and engaged in other extracurricular activities such as performing arts, poetry, or activism. He served as the external examiner for Daw Kyi May Kaung, former lecturer at the Institute of Economics in Rangoon, when the latter defended her PhD thesis at the University of Pennsylvania. She wrote of her mentor thus, “Joe was the only Burma expert I know of who gave up access to his country of study on principle but continued to research, criticize and write from his home in Princeton. In Burma I had not heard of him as his books were probably banned there. He joked that in the 1990s the junta had a cartoon where Burma experts were depicted as the six blind men with the elephant, “And I’m the one with a shovel near the elephant’s butt.”

In the spring of 1993, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, a vibrant place for area studies, brought him, (on my suggestion), to give a memorial lecture on Burma. Only half-dozen students showed up for his lecture, indicating an extremely low level of interest in Burma studies.

Undaunted by the absence of interest, Joe took his assignment seriously and proceeded to deliver his freshly prepared lecture with passion and erudition, as if he were talking to a packed audience at a learned society. As a great educator, he taught me a lesson by his professional conduct. After a meal together at a Turkish café, on State Street, that connects Madison downtown, with the campus, I walked away telling myself, “No audience or no job is ‘small’ for a self-respecting professional.” Thank you, Joe!

When Yale University Press commissioned me to write a contemporary history of Burma in 2010 the YUP editor in London showed me a blind review of my book proposal. I could most certainly detect Joe’s analytical signature. He wrote a very favourable review. I feel I let him down when I failed to keep my end of the book deal. No excuse. That was his last act of support for my activism and scholarship.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly – Joe was one of the very few western scholars I know (another is Michael W. Charney, my contemporary and now noted scholar of Southeast Asian Studies and Military Histories at School of Oriental and African Studies University of London) – who made compassionate efforts to give back to the people or “the subjects” – whom they study.

None of this typical one-way, instrumentalist approach to the study of Others – usually coloured bodies in politically repressed and economically wretched conditions.

This last quality alone of Joe, the scholar, will etch his name in my memory, and the memories of those, who had the great fortune of knowing him as a friend, a colleague, a fellow scholar, a teacher, and a comrade in the people’s struggle for freedom.

I wish I could travel to Princeton to bid him farewell in person at Princeton Cemetery, 29 Greenview Avenue, in downtown Princeton. His funeral is scheduled for 1 pm (local time), on Friday, July 2, 2021.

Maung Zarni