Winning Palme d’Or at Cannes, followed by several accolades at the Oscars is a very rare combination. And when that happens, one strikes both the boxes that matter the most. It is a certification of the fact that you have sold very well in the box office, globally; and also, made it big in the festival circuit – an ultimate dream come true for any sensible director (barring the delusional, self-destructive, super-cynical ones).

Parasite must have satisfied the producers, and seduced the critics and the audience alike. It has managed to lure the mainstream Netflix-bingers, and perhaps, also excited the die-hard Kim Ki Duk and Asghar Farhadi fans. It received universal hype, and this continues because it reflects a story of universal helplessness in the neo-liberal globalised era. Such world-wide appreciation is unprecedented in the recent past for a foreign-language film.

When the audience views a film with an overload of expectations, and is overburdened by content-recognition – suspension of criticism (if not disbelief) is quite usual. Yet when a September release is watched the next April, as an audience member, you are not in a rush to signal a verdict, or waste time in revealing narrative-unfolding. You can presume that most readers and viewers are aware of the plot-progression and its complexities. The dust has settled around the narrative twists and tropes. Instead one can focus on perspectives – or the reception of the class-question – or its representation of social-distancing even in pre-corona-times. Parasite has less to do with conflict between the classes, and a lot more to do with constant physical, spatial and social combating between the parasites struggling to survive – while manipulating and milking the rich.

Director Bong runs a parallel narrative of inter-class alliance and intra-class hostility. And that is not the subtext of the film, rather it is very much on its surface, overtly visible, particularly in the latter half.

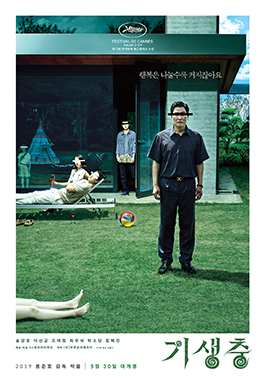

Poster for Parasite (2019 film). Wikipedia

Needless to say, these Parasites are the poor, marginal, and dependents.One set of parasites makes calculative moves to eliminate the other set. This strategic survival strategy is at the core of its narrative tension throughout. More than social mobility, it is sheer survival which is at stake. Tactics are being executed through parasitic creeping intrusions, infiltration, opportunistic-moves, and desperate manipulation. Combat between two parasites cause a high-voltage bloody, horrific, nihilistic climax that we love to view, reward and revisit – just like any underdog victory-narrative that bribes our guilt-ridden conscience. Parasites constantly try to outsmart and outgrow each other. Parasites try and remove each other from their respective locations, as the members of the labouring classes literally shift base by the end of the story. In this game, wherein one set of parasites try to take control of the other, their respective scores keep fluctuating, but the clash continues till the end. There is a compulsive tendency to climb-UP the stairs and move-UP from the basement in search of a BASE. It is a movement from one stingy over-flooded basement in the margins of the city to a pie of lavishly over-exposed elite-living, and then back to another dark and concealed basement beneath that lavish villa.

And what is the role of the rich? They are exclusive, but also selectively inclusive in certain ways, which fits their interest. The rich are cordial till the parasites – their tutors, drivers, maids – ‘cross the (class) line’. They are tolerant until their parasites smell of poverty and the subway. They are benevolent until the parasites show signs of being infected with contagious disease (or are plotted to be so by other parasites). And as soon as that happens, the rich smell threat. Termination without notice follows. Before employing the parasites, they require assurances of credibility, and weightage of recommendations. But otherwise, they are absolutely disinterested to probe into the personal lives of the parasites, or even bother to know about where they come from, and where might they disappear to after work. As expected, they are also indifferent to the catastrophe that floods the entire city, as they remain focused on organising birthday-barbeque-parties in their elevated lawns, wearing Red-Indian headgear. An overpour that chokes the settlements of the urban poor and drives them out of their basement – is merely a cause of the cancelling a camping-trip for the rich – and nothing more.

In the current corona-infected world, the rivalry could have taken a different turn, as millions have lost their daily wages, and there could have been a real possibility of antagonization against the rich.

But in a pre-corona world however, Parasite is not about inter class-conflicts, at all. Rather two sets of poor parasites are in conflict with each other to gather resources and survive. They are at each other’s’ throats all the time. Otherwise, the narrative strictly guards the status-quo, while the poor make constant attempt to take advantage of/from the privileged. While it acknowledges the social divide and the stark social inequalities, there is no agenda of any role-reversal or class-revenge. The emphasis on the literal and metaphorical desperation to climb-UP the narrow stairs, confirms the existence and sustenance of everyday life beneath the fancy glass house. In another basement, bugs bite, WiFi severs, strangers puke and urinate near the resident’s window, informal employers make up excuses for pay-cuts. Both these basements are visually in conflict with the BASE above. Architecturally, the massive expanse of the villa, the transparency of glass, size of the fridge and the furniture, the crockery and the kitchen, furnish opulence at its height. But the parasites are not avengers trying to forcefully take-over. They are very pragmatic. They realise their limits even though they are in awe of the wealth.

The parasites daydream to prolong their access by the means of appeasement, servitude, as if needing the imaginary courtship. The parasites think that the rich are nice because they are rich, and capital is seen as an ‘iron that smoothen all rough edges.’ The rich acknowledge their incapability to do any household work on their own, and hence their parasitical dependency on their drivers, tutors and maids are justified. This is a narrative of social dependency and solidarity with the class that is hierarchically superior on the vertical axis, and an extreme strife amongst the classes sharing the horizontal axis. And both these collaborations and contests are plotted simultaneously.

CANNES, FRANCE – MAY 25, 2019: South Korean director Bong Joon-Ho the winner Palme d’Or for the film “Parasite (Gisaengchung)” during the closing ceremony of the 72 Cannes Film Festival. Photo: taniavolobueva / Shutterstock.com

The ‘upstairs’ is not in conflict with the ‘downstairs.’ Rather the upper crust and lower ones are in workable social arrangements that are mutually beneficial for both. It is a peaceful adjustment, a convenient cooperation, and an indispensable collaboration. It’s not about lows-ceiling VS high-ceiling; or centres VS margin, or rich VS poor. Rather it is a full-fledged war between the pests. Envy and greed play between the parasites: parasites of the basement VS the parasites of the basement of the basement. It’s a fight between the underdogs of the undergrounds residing on two different levels, and who rises up on occasions. And when they do, consequences are severe and violent, as expected.

Parasite is not an anti-capitalist film, not that it claims to be one. Although it has been misinterpreted as one, by many viewers and critics.

Parasite is quintessentially a neo-liberal text reflecting heightened difference between the rich and the poor, and the intensified helplessness of the latter in the globalised urban milieu, where the poor is debt-ridden, and is denied social benefits. The working class not only has to struggle against members of the same class, but they have to ‘have a plan’ in order to carry out that fight. And after having lost everything, one of the parasites acknowledge that it is best not to have a plan at all, because not having a plan nullifies chances of failure to execute the plan.

Dreams of climbing UP the stairs, and to emerge out of the basement, and hold on to the BASE, continue to be utopian project for the parasites. As the parasites aspire not only to keep their heads above the basement, but they also desire to earn enough capital, one day, to take possession of the property by legal means, and to release one of the parasites stuck in the basement beneath the basement. That release is a universal hope of an impossible and improbable social mobility that nourishes the parasites globally.

SREEDEEP

SREEDEEP is a sociologist with Shiv Nadar University, India

https://www.sreedeep.net/home

Banner Image: New York City, New York / USA – February 22 2020: Marquee of the IFC Center in Greenwich Village announcing the movie “Parasite” as the winner of four Academy Awards. Photo: Erin Alexis Randolph / Shutterstock.com