The political rancour over Burma for many decades now has seen the image of a “divided Myanmar,” raised many times by many sides, even before independence in 1948 and regularly thereafter. Almost always it is positioned as a bad outcome and one that all should wish to avoid. Like Indonesia, a former colony whose colonial-era policies favoured division over national integration and left behind a country with numerous competing political, ethno-religious, and regional interests. Indeed, one could argue that colonial rule ensured that military rule would emerge and persist for so long in these two countries exactly because of that built-in fragility, Myanmar experiencing longer periods of military dominance than Indonesia.

Most of those fighting in Myanmar today do not do so for a “divided Myanmar.” They may not all agree on what Myanmar should look like, whether a strong Burman-dominated unitary state, with a great deal of military control, or a Federal Myanmar with power shared amongst the different “ethnic races.” They may also disagree on how inclusive a future Myanmar should be, as the vitriol against the Rohingya came not just from Burmans and Rakhine and not just from Buddhists. But most envision a singular Burma of some kind – their ethnic kin on the other side of Myanmar’s borders can be just as marginalised from the centres of economic and political power in India, China, Bangladesh, and Thailand.

One army in the vast array of other armed forces scattered across the inverted mountainous horseshoe of Myanmar has been built from other stuff. It has a long history, like other groups, of resisting Burman rule. But it had a much longer period of successful, separate development than other parts of the country with continuing myths of stronger claims to the original Burman language, connections with the Buddha, and ethnic seniority relative to the Burmans. Some Rakhine chronicles even claimed that the Burmans were the descendants of colonists from Rakhine into the Irrawaddy Valley. We cannot forget as well that Rakhine groups have been fighting Burman rule in Rakhine since the end of the eighteenth century and it was in part the continued raids of Rakhine by Rakhine rebels inside what was then British East India Company territory that led to the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26) and the British acquisition of Rakhine in the Treaty of Yandabo. All of Burma would not be unified again until the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885 and the annexation of Upper Burma by the British. Despite shared language, religion, and material culture, the Rakhine remained proudly loyal to their ethnic identity throughout colonial rule and after independence.

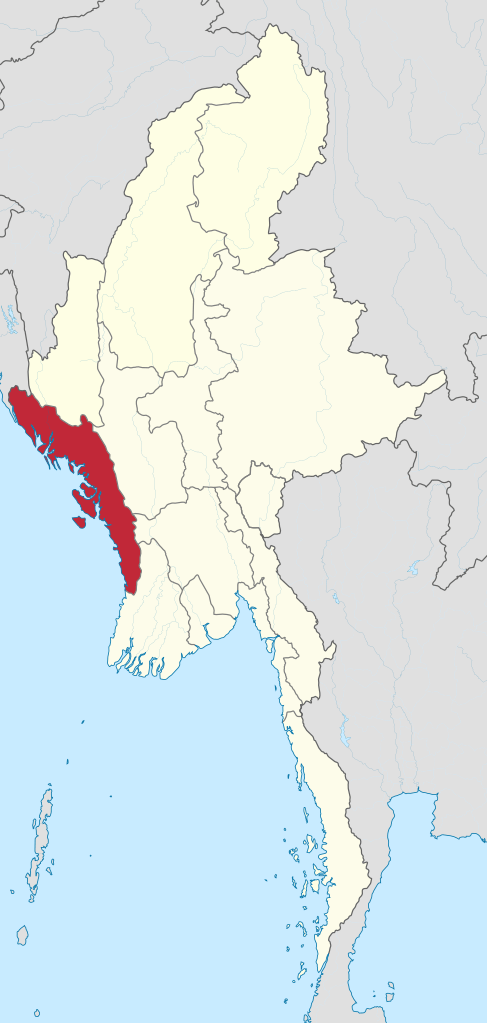

Location of Rakhine State (red) in Myanmar

Today, Rakhine has a number of reasons to entertain the thought of an independent future. One is the Rakhine Buddhist fear of being overwhelmed by Muslim immigration, which was a major factor in problems with the Rohingya. While the Tatmadaw several times chased large numbers of Rohingya out, the attacks in August 2017 so thoroughly removed so many Rohingya, followed by the bulldozing of their villages, and the construction of a fence along the borders with Bangladesh to prevent them from returning that they removed the main reason that the Rakhine Buddhists saw the Tatmadaw as useful allies. Worse, very soon after the Rohingya were expelled, the Tatmadaw fired on and killed a number of Rakhine Buddhist ethno-nationalists to reinforce ‘law and order’ under Tatmadaw control. Full-blown conflict then erupted in 2018 between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw and then after, after a ceasefire in November 2020, but then broke out again in August 2022. Clearly, a Tatmadaw-dominated Myanmar will not give the Rakhine the kind of autonomy they would require.

Just as clearly, the Arakan Army will not have much to look forward to in a National Unity Government (NUG) version of Myanmar, whether truly Federal or not. For one thing, it was a National League for Democracy government that had backed the Tatmadaw war against the Arakan Army in the first place and denied most the ability to vote in the 2020 elections. But the main reason is that this government will for various reasons have to present itself as committed to civil liberties, human rights, and the like and will be in a position where it will be difficult to refuse resettlement by the one million or so Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. The Arakan Army leadership, in particular General Tun Myat Naing, has continued until the present to repeat the language of a much more limited re-entry of some Rohingya under certain conditions and to indicate that he rejects the claims made to indigeneity by the Rohingya.

The Arakan Army’s seemingly Quixotic behaviour in standing by during the Civil Disobedience Movement period after the 1 February 2021 military coup while playing a significant role in training different ethnic armies to fight the Tatmadaw and then taking part in the Three Brotherhood Alliance (formed in 2019 by the Arakan Army, Kokang’s Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Ta’ang National Democratic Alliance Army) is really only explainable as part of a strategy to encourage the break-up of Myanmar to give the changes for its own separation from the country greater chances for success. The more they can roll back the Tatmadaw, one chief threat, and the more they can aid some of the ethnic armies and limit to ability of the NUG to win or after victory centralize power, the Arakan Army will have a greater ability to govern Rakhine on its own. At different times, the Arakan Army has adroitly won concessions from the Tatmadaw and a friendly tone from the NUG when it needed to, without a permanent commitment to a deal with either, while it has concentrated on competitive governance in Rakhine and support services for the civilian population. This certainly would help pave the way within the region for a stable transition to fuller autonomy or independence.

The Flag of Rakhine

But could Rakhine separate from Myanmar and survive on its own? While other regions have been economically stripped by occupying Tatmadaw forces or companies acting under their protection, Rakhine has been left much more untouched for longer. Its greatest economic potential lies in special economic zones that might be set up to service the growing Bangladesh economy, the passage through Rakhine of Chinese pipelines, and the extraction of offshore natural gas and oil. Rakhine benefits from a mountainous barrier between itself and the rest of Myanmar which is one reason it was able to stay separate for so long from its eastern neighbour. Another reason it could do so was because of the commercial access afforded by its long coastline on the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal, which today is becoming a very lucrative economic zone in the context of China’s One Belt One Road Initiative, but also because of the economic growth of India and Bangladesh. No other ethnic army, arguably (very easily so), is as well-positioned for a successful and economically attractive separation from Myanmar.

Michael W. Charney

SOAS, University of London

Banner: December 2021: Young Arakan Army solder at Remakri. Photo Masum-al-Hasan Rocky Wikipedia Commons