Only a few days remain before the International Court of Justice1 rules on Myanmar’s preliminary objections to the jurisdiction of the Court and on its application to dismiss in The Gambia v. Myanmar. This is only the third time the ICJ will rule on an alleged violation of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide2. In Bosnia v. Serbia and Croatia v. Serbia, the ICJ made the Genocide Convention almost unenforceable against States. This case represents an opportunity to correct the Court’s errors in those cases.

If the Court were to decide that it has no jurisdiction, and the case is therefore inadmissible, it would deal a fatal blow to State accountability for violation of the Genocide Convention. In its ruling on Provisional Measures, the Court has already indicated that it is likely to find that it has jurisdiction.

When it decides on the merits of The Gambia’s claim against Myanmar, the Court will have the opportunity to correct its fatal mistakes in Bosnia and Croatia.

– WATCH LIVE HERE –

In both of those cases, the Court held that to prove genocidal intent, destruction of part of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group must be the only intent that could reasonably be inferred from the acts of a State. The Court held that “ethnic cleansing” was another possible intent of Serbia. Therefore, special intent to commit genocide was not Serbia’s only intent, and Serbia could not be conclusively proven to have violated the Genocide Convention.

The ICJ applied a logic of exclusion. If there could be any other possible intention, then the special intent to destroy could not be conclusively proven.

This concept of intentionality does not accord with international criminal law or even with ordinary criminal law. It would make it impossible to convict any murderer if the killer also had some other intent such as robbery. Nearly every human act has multiple intentions. Actions of States in all their complexity and their many officials must have even more intentions than acts of individuals.

The Court’s interpretation of intent in the Genocide Convention will make it nearly impossible to prove that any State has violated the Genocide Convention. China’s oppression of the Uyghurs has included every act of genocide enumerated in Article 2 of the Genocide Convention. But China claims it is not committing genocide because its intention is to prevent terrorism and counter Uyghur separatism. China seems to have studied the ICJ’s judgments in Bosnia and Croatia. The Court handed China a “Permit to build a jail” card.

Listen: BBC World Service Newsday Program with Maung Zarni, February 21, 2022

In The Gambia v Myanmar, the ICJ must move away from its requirement that destruction of a group must be the State’s only intent. Forced deportation (“ethnic cleansing”) through terror may be one objective of genocide. The two intents are, logically, not incompatible and mutually exclusive as has been argued in an influential treatise.3 In fact, the crime of deportation and the crime of genocide often go together. Indeed, the Holocaust shared these and many other intentions and it would be perverse in the extreme to argue that, therefore, the Holocaust was not a genocide.

Norms that prohibit genocide have become customary law norms. According to Article 38, para. 1 of the ICJ Statute, the primary sources of law that the Court will consider in its decisions, include treaties (or Conventions), customary law, and general principles recognized by civilized nations. Customary law does not require the support of all nations, but rather requires a course of conduct widespread among the majority of States (a “general practice accepted as law”, not a uniform one), together with the belief that such conduct is juridically binding. No State can claim immunity from customary norms, including the prohibition of genocide.

As soon as a customary norm crystallizes, such as the prohibition of genocide, all nations must legally comply with it, including those States that have not ratified a convention4. The ICJ should take into account not only the Genocide Convention, but also the customary norms prohibiting genocide. Myanmar ratified and deposited the Genocide Convention on 14 Mar 1956. Myanmar is also bound by the substantial customary international law that has developed since then.

The prohibition of genocide is a jus cogens norm, which confers on it imperative duties superior even to primary customary norms. The importance of this case lies in the fact that it concerns the violation of a convention prohibiting the “crime of crimes” under international law.

In addition to correctly applying the substance of the law, the ICJ should not allow the military junta to represent Myanmar in this case. Recognition of a government differs from the recognition of a State. This junta is illegitimate not only because it overthrew a legitimately elected government, but also because of the atrocities it has committed against the people of Myanmar, including the Rohingya. Those very crimes are the subject of this case. The junta is an unelected military dictatorship that is currently shunned by other nations and nearly every international forum. As such, the appearance of the junta before the ICJ would not be in accordance with international law, and so the Court should not allow it.

Enforcement is one of the primary attributes that constitute law. If a law cannot be enforced, it can no longer be considered law. It is crucial that the ICJ’s judgment in The Gambia v. Myanmar be used to correct the ICJ’s erroneous requirement that genocide be the only intent of a State to prove its special intent to commit genocide. This case will have an enormous impact on the enforceability of the Genocide Convention and it demands the greatest care. Indeed, it will determine whether the Genocide Convention can continue to be considered international law.

Giada Corsoni is Coordinator and Legal Associate with Alliance against Genocide

Gregory Stanton is founding President of the Genocide Watch

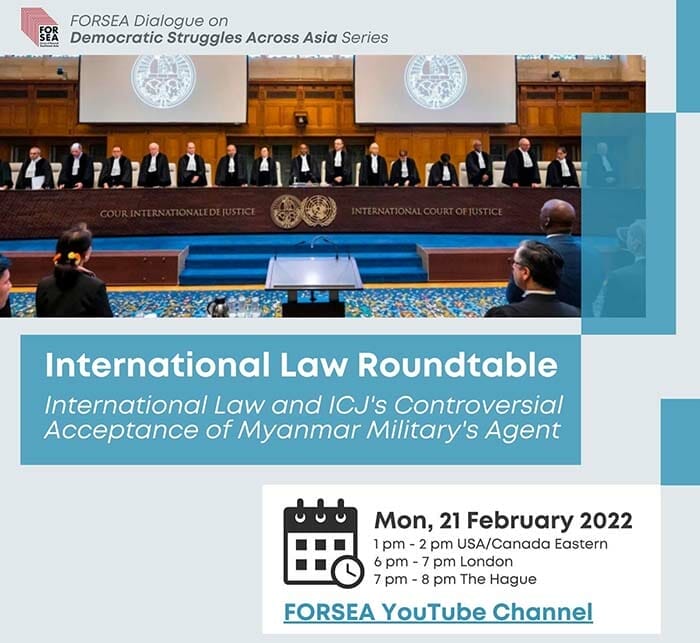

FORSEA Dialogue on Democratic Struggles Across Series

International Law Roundtable

International Law and ICJ‘s Controversial Acceptance of Myanmar Military’s Agent

Join us live on Monday 21 February, 2022

1 pm – 2 pm (USA/Canada Eastern)| 6 pm – 7 pm (London)| 7 pm – 8 pm (The Hague)

L I V E

Watch LIVE on FORSEA YouTube Channel

Guests

- Erin Farrell Rosenberg, a US attorney, formerly with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia & the International Criminal Court (ICC) a member of the American Bar Association Working Group on Crimes Against Humanity, Visiting Scholar with the Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights at the University of Cincinnati School of Law.

- Gregory Stanton, Founding President of the Genocide Watch and former President of the International Association of the Genocide Scholars

- John Packer, Neuberger-Jesin Professor of International Conflict Resolution & Director | Human Rights Research and Education Centre (HRREC) University of Ottawa

Host: Maung Zarni, Co-founder, FORSEA & Free Rohingya Coalition and Adviser to the Genocide Watch