This week Aung San Suu Kyi’s fairy like re-emergence into the international policy circles was reported by Thai Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai at the Association of South East Asian Nations Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Jakarta hosted by the current and rotating Chair. Jailed on trumped up corruption charges, and held incommunicado by Myanmar’s coup junta, the ousted civilian leader reportedly “encouraged dialogue” with the widely hated junta engulfed in multiple crises.

I do not doubt that the reported meeting took place. No official would concoct such a story. Having studied her leadership over the last 30 years, I also do not second guess the Thai guest’s relayed message that she is “open to dialogue” with the repressive military, or she “encouraged dialogue” amongst all warring parties in Myanmar’s perennial domestic conflict. On so many public and media occasions, including BBC’s Flagship Radio 4, the populist leader has said repeatedly that she “genuinely (read unconditionally) loved” the soldiers whom she felt were surrogate “brothers” serving in the army which her martyred father Aung San founded and led.

Love in the way one feels about a particular institution or particular population may be understandable – as in nationalism or patriotism. But it is both unprincipled and counter-productive for Suu Kyi to be voicing support for dialogue with no preconditions with the mass-murderous regime in Naypyidaw. Even as she was meeting the Thai visitor for over an hour, her military jailors were routinely carrying out air strikes against pro-democracy civilian communities – not as “collateral damage” but as “legitimate targets” – or severely restricting the humanitarian activities of international bodies including United Nations’ agencies and INGOs –to provide emergency support to nearly 2 million people displaced by violence. That’s roughly the total number of Rohingya people about half of whom fled the genocide in Western Myanmar in 2016 and 2017.

Against this backdrop, the jailed and failed transitional leader’s support for unconditional dialogue with the killers has potential to do more harm than good to the common mission of at least ending violent and oppressive military rule through both peaceful civil disobedience and widespread armed revolt.

There are four problems with her call for dialogue.

Problem one

First, the leaders of the National Unity Government (NUG) and the Committee Representing People’s Hluttaw or Parliament (CRPH) have repeatedly urged their grassroots supporters to support the NUG-led armed resistance. These leaders have been driving home amongst Myanmar public their central message – the blood debt precludes any talk (with the cruel military) – at every opportunity. How does Ms Suu Kyi’s message of “open dialogue” square with the anti-coup resistance’s consensus message of national liberation, as it were, by any means necessary? After all, these NUG and CRPH leaders view themselves as “second” and “third line” leaders from Ms Suu Kyi’s ousted National League for Democracy.

Problem two

Second, this message by NUG and CRPH has obviously resonated very well with the public, which has in turn resulted in “donations for the revolution”, to the tune of over $100 million. It is this grassroots financing from the Burmese public in Myanmar, neighbouring countries and western countries, that has sustained the armed resistance and the Civil Disobedience Movement. Notably, there has been an absence of material and financial assistance from any state during the 2.5 years old resistance movement. Even the United States Government – and the Congress – have limited the American support to “non-lethal assistance” while having poured nearly $80 billion worth of arms and other forms of support into Ukraine’s resistance in less than 2 years.

Wise or not, the anti-coup public want to see the complete eviction of the military. They want to see the genocidal generals dragged out of power by the latter’s feet, literally. For the military has, since the coup of February 2021, been engaged in what I would call a series of “mini-genocides”, that is, scorched-earth methods of destruction of pro-democracy villages and neighbourhoods throughout different ethnic regions including Myanmar Buddhists in the central plains of Saggaing and Magwe, as well as ethnic Chin in the highlands in Western Myanmar and Karenni in the region next to Thailand.

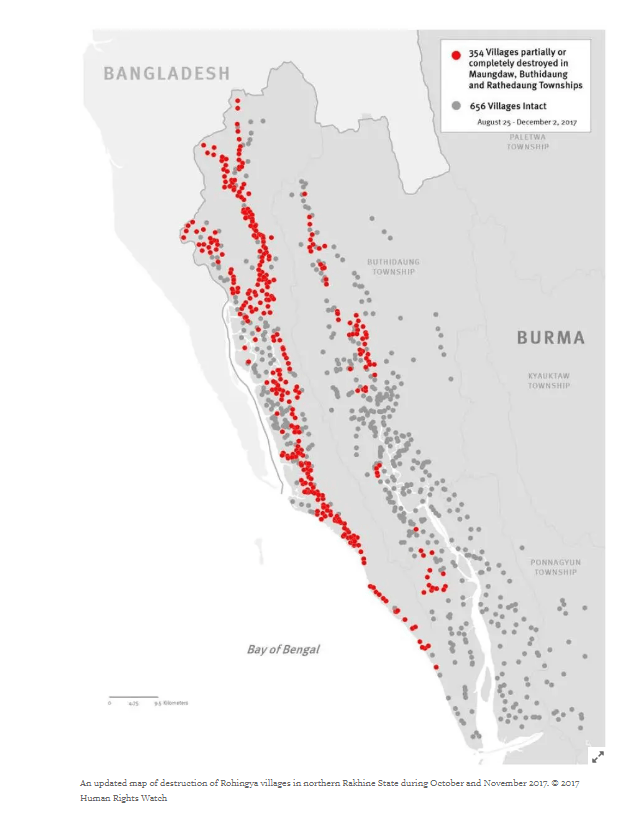

To get a sense of the scale of death and destruction, over 64,000 homes have been torched or otherwise destroyed by the junta troops in the last 2 years since the February coup of 2021. This figure is almost twice as big as 38,000 Rohingya homes (in over 300 villages) destroyed during the same military’s 2017 wave of genocidal destruction. [See the US Holocaust Memorial Museum reports on Rohingya genocide here].

What would happen to the financial and community support to the armed resistance that has not only sustained its momentum but took territorial and administrative control of some of the most important heartland’s regions? Saggaing and Magwe historically provided the largest number of military recruits to the country’s armed forces. Even these Bama Buddhist nationalist enclaves no longer accept the junta as their Bama brethren. Likewise, ethnic resistance organizations in the important frontier states such as Chin and Karenni regions have practically driven out a large number of the junta troops from their regions.

Problem three

Third, as Tria Dianti wrote for the Radio Free Asia, groups representing Myanmar’s civil society met just last week with Ngurah Swajaya, the head of the ASEAN Special Envoy’s office and delivered their unadulterated “No” to any talks with Myanmar junta, which they rightly characterise as “terrorist”. During the meeting, this coalition of grassroots resisters spelled out to the Indonesian diplomat the coalition’s official position: “the Special Envoy’s official engagement with the illegal military junta is inconsistent with ASEAN’s decision and stance to exclude and ban members of the military junta from all high-level ASEAN meetings.” Their message – delivered less than 7 days ago – is diametrically opposed to Ms Suu Kyi’s “openness to dialogue”.

Amongst the participants were representatives of both armed and non-violence organizations with national reach including Bamar People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), Chin Students’ Union of Myanmar, General Strike Collaboration Committee (GSCC), General Strike Committee (GSC), General Strike Committee of Nationalities (GSCN), General Strike Coordination Body (GSCB), Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM), Kachin State Civilian Movement (KSCM), Karen Student Network Group (KSNG), Karenni Nationalities Defense Force (KNDF), and Sagaing Forum.

Many of these networks are made up of, and led by, Generation Z resisters and other progressive Myanmar dissidents. They openly embrace Rohingya as integral part of Myanmar’s ethnic tapestry and disdain Ms Suu Kyi’s collaboration with (her) “Father’s military” whenever the troops launch vicious military operations against Rohingya, Kachin, Rakhine Buddhists, farm and labour activists and journalists. They are not going to be swayed by Ms Suu Kyi’s empty encouragement for dialogue, or external actors’ message of pacificism in the face of the junta’s brutal and relentless repression.

Will these mutually exclusive stances – Ms Suu Kyi’s dialogue with no preconditions or the general consensus in the resistance, no dialogue whatsoever with the terrorist junta – tear the society apart?

Troublingly, these fundamentals differences will likely trigger the horizontal violence amongst armed resistance groups, between those still blindly loyal to Suu Kyi, and those segments of the resistance that have embraced the post-coup revolutionary movement as a genuinely democratic alternative to Aung San Suu Kyi’s domestically failed and globally disgraced leadership?

The first political amnesty announcement, to all “insurgents”, dated 1 April 1963, issued as a broader framework for “nationwide peace”, signed by Gen. Ne Win, the Chairman of the Revolutionary Council, the coup junta.

Problem four

Fourth and finally, there is a timely and crucial question to be raised about Aung San Suu Kyi’s moral leadership, political integrity, and intellectual capacity to think through difficult challenges that have confronted the country in turbulent transition.

After all, even with her unfettered access to expertise, advice, public opinion and intelligence reports, Aung San Suu Kyi, both as opposition leader and subsequently the de facto head of state, has made a series of monumental errors with long-term consequences for the country – and her people.

As the opposition leader, she railed against farm and rural protest movement that sought to mitigate the devastating ecological and communal impact stemming from the Chinese mining projects, jointly conducted by the military. As the State Counsellor, the position she called “above the president”, she sung the official praise of Myanmar’s military while the latter launched military operations against Rakhine Buddhists, and her civilian Telecommunications Ministry shut down the Internet for the entire state of Rakhine for 2 years. And most infamously, she chose to defend the indefensible when she turned up at the International Court of Justice to defend and deny the military’s genocide against Rohingya Muslims. Remember how for months she justified prosecution of the two Burmese journalists working for Reuters on grounds of national security: they had the hard evidence of the military’s genocidal massacres, and they were trying to do their job of reporting on the factually verified story.

For its own bloc interests, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of course, is likely to capitalize on Suu Kyi’s message of “openness to dialogue” to continue to tinker with its fruitless 5 Point Consensus (5PCs), which many Myanmar analysts see as “dead upon arrival”.

Dictators do not dialogue. They manipulate it. Nationwide “peace dialogue” was initiated by Ne Win’s regime called Revolutionary Council in 1963. Those who don’t appreciate #Myanmar‘s abysmal history of ceasefires/dialogues will continue to support it, with no preconditions. pic.twitter.com/qt4SHRMds8

— FORSEA (@officialFORSEA) July 13, 2023

I for one see no bright prospect in either ASEAN’s efforts or Aung San Suu Kyi’s hold on certain segments of Myanmar public.

Ms Suu Kyi’s abysmal record on neo-liberal economic policies, anti-Muslim racist politics and typically autocratic decisions have clearly demonstrated that she lacks a clear federalist democratic vision. And equally important, she shares the military’s Bama Buddhist chauvinism wherein both her policies and the military’s treat the non-Bama ethnic communities as “junior partners” in nation-building.

By way of prediction, she will continue to speak in her characteristically vague and empty rhetoric of “dialogue.” Ms Suu Kyi’s captors will carry on using any process of dialogue, not to seek lasting peace or build a new kind of politics based on the federal principles of ethnic group equality and democratic control of the country’s armed forces, but rather to wiggle themselves out of the violent corner they have created for themselves. After all, it is the original coup regime of 1962 led by General Ne Win which launched nationwide “peace dialogue” in 1963 while it and successive military regimes have since proceeded to plunge the country into further strife and turmoil in the ensuing 60-years.

Tragically, the public will become increasingly confused as to who is providing the pro-democracy leadership or which path – revolutionary or the status quo of the Suu Kyi-military deal, which will undoubtedly be backed by ASEAN.

Maung Zarni

Banner image: Aung San Statue Yangon, Wikimedia Commons, & Aung San Suu Kyi historical figure, Wikimedia Commons.

Read “What has gone wrong with the Norwegian peace initiative in Myanmar and how should it be fixed?” Zarni, January 2013