Thailand held its general elections on May 14, 2023, on the same day Turkey held its. In Turkey, another round was held a week later which determined outright majority winner. The incumbent President Recep T. Erdogan was declared the clear winner, and the swearing-in ceremony followed on June 3. In sharp contrast, in Thailand, a month after the general elections, the Thai national Election Commission has yet to officially endorse the results.

Now we, the Thais, are all left playing the guessing game, in the midst of so many bewildering moves, as to who would be the next Prime Minister, or which parties would form a coalition government. Even the post-election analyses appear premature at this point in terms of the direction Thailand may be heading.

There are too many un-knowns to be confident about one’s own analysis.

As a matter of fact, in our 90 years of history of Thai “democracy” since the 1930’s when the early reforms of the traditionally absolutist monarchy were ushered in, we have never, even once, found ourselves in this kind of situation.

For international observers with an interest in the political developments in Thailand, the unfolding events in Thai electoral politics might be rather puzzling.

Given this emerging bizarre situation where the leader of the election winning party has to go around and lobby for further support for his Premiership and for his victorious party among both the elites and the electorates.

In this short essay – which I call “A Brief Guide to post-Election Politics in Thailand” – I offer some insights as to how best to understand what is unfolding politically in post-election Thailand and what likely scenarios there are in terms of the establishment of the next government.

Example of the 2023 Thai General Election posters. Wikipedia Commons

The Four Political Actors or Forces who are most Impactful in Thai National Politics

I don’t think I have found any better analysis on this subject than the one put forward back over a decade ago by a distinguished Thai/British academic couple, who brilliantly identified modern Thai politics as a saga of power plays and fighting for power by the four contesting forces, namely:

- Royalties – the people who held an absolute control of Thailand before 1932 and somehow managed to retain immense influence on what is going on in the political economy of Thailand;

- Military/bureaucrats – the armed bureaucrats in soldier’s uniform who assumed enormous power since the abolition of the absolute monarchy in Thailand in 1932. They have since dominated the nation’s political life, incessantly looking for opportunities to intervene in the forms of coups, putting themselves in state offices and assuming directorships of various companies. Over the past 90 years, we have seen 13 coups and many more coup attempts. Looking back, one can say that the nation’s popularly elected governments have been allowed to assume power, without any military’s undue interference altogether for roughly a total of about 10 years;

- Bangkok-based tycoons – this relatively overlooked force emerged in the Thai political scene following a period of rapid economic growth in 1960s and 70s, bolstered by the massive economic and military assistance by the United States, and the equally massive military spending and build-up during the Vietnam War. These people have been drawn (or inserted themselves) into the political circles, chiefly as financiers for the military and the royalties’ political machines in exchange for the royal protection of their business/corporate interests. They entered as clients in the royal and military patron-client relations while securing various types of rewards and privileges.

- The “provincial riches” (in Thai “Baan Yai”) – the emergence of this force came after a period of massive government spending in the provinces in support of rural development and the distribution of wealth from Bangkok into the other areas of the country. This made it possible for some local people with means and connections to start accumulating massive quantity of wealth by securing lucrative contracts for the construction of roads, schools, hospitals and other public utilities. , As their wealth grew they went a step further by entering (or buying their way into) provincial and national politics in order to gain further social recognition, national influence and greater wealth. Starting as provincial members of the Parliament, they have built themselves as one of the most formidable forces in Thai politics since late 1980s while managing to establish formidable administrations over a considerable period.

It is crucial to understand that what transpires in Thai political economy and politics is the outcome of the interplay of these aforementioned political actors/forces. They have without a doubt shaped Thai politics. That is, until the previous general elections in 2019.

A Break With the Past

Then, shortly before the 2019 elections, a new social force emerged, something the two academics didn’t forsee when they wrote their clear-eyed analysis of the players in Thai politics 10 years ago.

This new player was born entirely outside the parameters of the old four political forces. They built themselves as a political party of the ordinary, the young ones, and of the people on the periphery, not under the “ownership” of any wealthy families or individuals. They developed a platform that resonated increasingly well with the electorate, both in the megacity of Bangkok and in the provinces, that have grown tired of old-styled patron-client politics, rampant corruption, pervasive abuses of state power, intimidations and routine restrictions on the basic rights and freedoms of ordinary citizens.

Based on both the clear description of Thai national politics and my own additional understanding, I would now like to venture into identifying which party represents which force in the 2023 general elections.

Of the ten major political parties contesting in this year’s elections, we could group them into three “axises”:

1) The (incumbent) military-royalties-tycoon axis

This axis is represented mainly by two parties. They are A) Ruam Thai Sang Chat, the party led by Prayut Chan-O-Cha, the coup leader who established the many mechanisms and procedures in the current Constitution, designed to enable himself to stay on as Prime Minster at least for 8 or 9 years, under the name and B) Palang Pracha Rath, the party led by his deputy, Prawit Wongsuwan, Both parties are the torch-bearers for the conservatives and a joint undertaking of the royalties, the military and the tycoons. They rhyme in Thai as Nai thun (tycoons), khun suek (warlords) and sakdina (feudalists).

And to some extent, the third largest party in the parliament, Bhumjai Thai, could also be categorized as an ally or a component of this nexus. It is led by one big tycoon with deep connection to both the military and the palace. In fact, in their DNAs, Bhumjai Thai and Chat Thai Pattana are also “Baan Yai” (provincial riches). But what makes them different from Puea Thai is these two parties have already been absorbed into the folds of the royalties-military- tycoon axis, while Puea Thai has been kept outside.

The Democrats, the country’s oldest political party (founded in 1946), could also be described as part (or at least another ally) of this camp.

This axis also includes two other smaller parties, Chat Thai Pattana and Chat Pattana Kla. They have their own support bases in small enclaves in the country’s central plains and in the northeast, respectively.

2) The provincial riches (Baan Yai) axis

The fugitive former PM Thaksin Shinawatra’s party, Puea Thai, is undoubtedly a key vehicle for the Baan Yai (provincial riches) axis. They have for decades built their strong support bases in the northeast and the north. The northeast region is the most populated, and the electorates there send one third of the nation’s constituency MPs while the north is centered around Thaksin’s hometown of Chiang Mai, the region’s capital. In fact, Thaksin’s party (under three different names) won in all Thailand’s general elections since 2001, typically with an outright majority.

This party has been the main victim that fell to the past two military coups. The party has functioned as Prayut’s main critic/adversary in the past few elections. In the 2023 election it has emerged as a key component of the democratic camp.

3) The Third Axis

This third axis encompasses the country’s youth, the new faces, the liberal, the periphery (labour, ethnic groups, LGBT, etc.), who come together only in 2018 to seek to challenge the domination and monopoly in the nation’s political and economic spheres by the Old Guards, that is, the tycoons, the generals and the royalties. These new and progressive social forces formed a new political party – named Future Forward – and contested in the 2019 elections wherein they surprised everyone with their victory for 80+ seats in the previous Parliament. But the Future Forward’s founding leaders were removed by the Constitutional Court on flimsy judicial grounds. This removal was widely seen until now by the Thai public as a politically motivated attempt aimed at weakening the party. The party later regrouped and renamed itself “Move Forward”, this time led by a young Harvard/MIT graduate, Pita Limjaroenrat.

In one sentence, we could call this latest election a three-way race, interestingly resembling the stories in the Chinese classic epic, (the Romance of) the “Three Kingdoms”.

The incumbent, Prayut Chan-O-Cha, a Thai politician and retired army officer who has served as the Prime Minister of Thailand since he seized power in a military coup in 2014.

What are the key issues in the election campaign?

For the incumbent, they mainly sell the personality of Prayut Chan-O-Cha as a man of honesty, a man staunchly loyal to the Monarchy, and a man of experience (having served as Prime Minister for nine years). They also sell their “achievements” and, if allowed, their continuity.

Prayut’s (seemingly estranged) sister party led by his deputy, Prawit Wongsuwan, also sells their experience, their pragmatism. But having seen a window of opportunities in a deeply divisive Thailand, the party also runs on a campaign to forge reconciliation and unity of the nation.

Similar to the incumbent party, Thaksin’s Puea Thai also campaigned on their (distant) past successes – when Thaksin and his sister, Yingluck, led the government ten years ago. Additionally, they held up their entrepreneurial ability and enterprising skills to fix the nation’s worsening economic woes, promising to cut down the cost of living for the Thai voters, boost the latter’s incomes and expand their (business) opportunities. In short, Puea Thai’s campaigning platform was more economic than political and more on experience and past successes. Cleverly, in their own way, they also sought to exploit the people’s sense of boredom and weariness of the incumbent PM and coup leader Prayut. Puea Thai appealed to the people to give them a “landslide” victory to ensure that they have enough MP seats to form a government of their own. Concurrently, they were engaged in negative campaigning by making assertions that a vote for other parties (specifically alluding to the Move Forward party) is a waste of opportunities to remove the widely unpopular Prayut. As a matter of fact, Thaksin clan’s Puea Thai party and Move Forward party competed for votes in the same support base, undercutting each other. This practice in fact enabled candidates from the other camp to win eventually. Puea Thai’s assertions were subsequently proven totally false. Puea Thai was, in due course, exposed in having resorted to tricky campaign strategies.

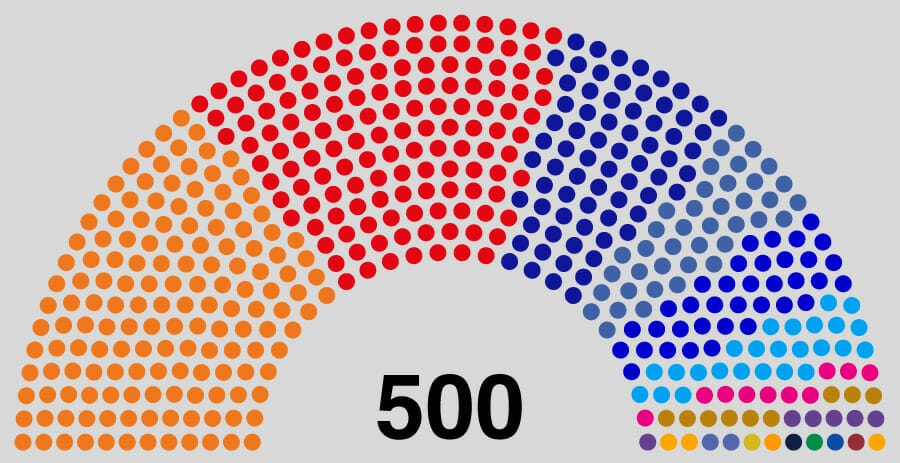

Here digression is in order. It is noteworthy that the current Constitution allows 250 appointed senators – appointed by Prayut – to join 500 duly elected-MPs in voting on Prime Minister candidate(s). Therefore, in order for a PM candidate to get elected, he or she has to garner at least 376 votes of the two combined chambers, the parliament of elected MPs and the Senate made up of the incumbent-appointed senators.

In sharp contrast to Puea Thai’s economy-focused election campaign, the Move Forward campaigned on a totally different ticket. The young party instead called for an end to the military’s domination in politics, business monopoly, and decentralization of administrative power (from Bangkok to the provinces) or “de-militarize, de-monopolize and decentralize”. They also campaigned on the need to undertake a wide range of structural or institutional reforms, develop a welfare state to ensure that vulnerable segments of the Thai society are looked after, while promoting progressive social values such as promotion of gender equality, LGBT rights, and, perhaps most controversially, on the reforms of the monarchy.

While the other two parties, the Democrats and Bhumjai Thai, campaigned on relatively mundane issues – which went largely unnoticed by the public – except for one big thing. Bhumjai Thai proposed free(er) medical uses of cannabis (as well as recreational uses, which ignited voters’ interest. This single issue became a subject of serious and popular debates.

Who are the winners and losers?

Of the three camps contesting in this year’s elections, the incumbent Ruam Thai Sang Chat party clearly suffered the greatest electoral losses. The Prayut/Prawit parties received together only 5.3 million votes (on the party-list ballot), a sharp drop from the 8 million votes they received in the elections 4 years ago (in 2019). The number of MPs elected (on both the party-list and constituency) for both parties were 76 as opposed to 119 in the previous elections in 2019). Their coalition partner, the Democrats party, was also dealt a humiliating defeat by the Thai voters: the Democrats got only 0.9 million votes (on party-list) and the total number of MPs were 25 as opposed to 53 in 2019 elections. Bhumjai Thai is the only party in the incumbent coalition that managed to return with more or less the same number of seats/MPs as they held in the previous parliament.

Thaksin clan’s Puea Thai party also suffered “quite” a humiliating defeat. Puea Thai campaigned on the bold claims the leaders had made, and hoped, that they would win an outright majority. They were aiming for “a landslide”, as they put it. With the (anticipated) outright majority, Puea Thai party leaders were hoping to form the largest party in the next parliament. At one point, they were publicly declaring that their aim was to capture 310 MP seats. However, the aim proved overly ambitious: the party ended up with only 141 seats. However, Puea Thais party-list votes saw an increase of voters – from 7,9 million votes in 2019 election to 11 million votes in the 2023 elections while the number of Puea Thai MPs increased slightly from 131 in the previous elections in 2019 to 141 in this year’s elections.

The only winner in this year’s general elections is the Move Forward party, that managed to see their popular votes rose from 6.2 in the previous elections of 2019 to 14.5 million votes in the May 2023 elections. Move Forward’s vote tally was 39% of the total votes cast, handing the party 151 seats in the parliament, which in turn made Move Forward the party with the largest MP seats. The Move Forward’s performance – and popularity – had proven election pollsters and pre-election projections completely wrong.

Move Forward Party supporters celebrate the party’s election results in Bangkok, May 15, 2023. Photo, Chaiwat Subprasom, Shutterstock

Why did the Move Forward come out on top?

In a nutshell, Move Forward’s stunning victory could be attributed to a number of crucial factors. Among them are the party’s outstanding performance in the past Parliament (called after the 2019 elections); the conducive atmosphere prevailing in Thai society (wherein people are wearied of worsening Thai economy where Thailand is falling behind even Vietnam); the pervasive abuse of power; rampant corruption; Prayut government’s harassments and intimidations of the political opposition and vocal critics of the government; the governmental manipulation, perceived and real, of mechanisms designed to serve as democratic checks-and-balances (for instance, the judicial branch) – which often ruled in dubious legal reasoning in favor of the government); straightforward positioning on key political issues (such as whether or not the Move Forward would join a future Prayut/Prawit-led coalition government). Besides, the Move Forward candidates and leaders were far more appealing than their rivals while the party’s platforms were sensible. Both their debate performances and the effective use of social media in the campaign (for instance, TikTok) were significant factors behind the party’s surprise victory as the Number One winner.

Their slogan “Vote Move Forward, Thailand will never be the same again” resonated extremely well the majority of the Thai public. In Bangkok, Move Forward swept the entire metropolis area, with 32 out of 33 seats contested, and grabbed 48 percent of the ballots cast. Even in the only constituency they lost to Puea Thai, they lost by just 4 votes. As a matter of fact, the Move Forward won in a similarly sweeping fashion in even Thaksin’s Northern Thai stronghold/hometown of Chiang Mai.

What are the implications?

Move Forward’s victory has stunned all the key players in Thai politics, be they the royalties, the military, the tycoons, even people in Thaksin’s camp. It was something they least expected. All the power-elite and counter-elite were caught off guard by the Move Forward’s decisive win. The Move Forward party is perceived to have a “radical” political agenda (against the Triumvirate Establishment of Military/Royalities/Tycoons), however. That perception of the anti-Establishment agenda appears to pose a threat to the Thai power-economic establishment, which in turn makes the latter feels they have no other choice but to block the election winner from forming or leading the post-election government.

Allowing the Move Forward to lead the government or even joining the Move Forward-led government would mean Thailand would undergo sweeping reforms. The fundamental reforms necessarily threaten the Establishment. There would be no more status quo. The Establishment has so much at stake. Their unchecked political power, standing in society and the unwarranted privileges which they have enjoyed for nearly a century since the last radical reforms of the 1930s are clearly at risk.

Unfortunately for the Thai electorates who want and demand meaningful reforms of their semi- or quasi-democracy, the defeated Prime Minister Prayut and his cohorts still have, under the present Constitution, countless means at their disposal in order to make it harder, or even impossible, for the election victor – the Move Forward party, in particular its leader, Pita, – to form the next government.

Move Forward: 151 seats | Pheu Thai: 141 seats | Bhumjaithai: 71 seats | Palang Pracharath: 40 seats| United Thai Nation: 36 seats| Democrat: 25 seats | Chartthaipattana: 10 seats | Prachachart: 9 seats | Thai Sang Thai: 6 seats | Chart Pattana Kla: 2 seats | Pheu Thai Ruamphalang: 2 seats | Thai Liberal: 1 seat | New Democracy: 1 seat | New: 1 seat | The Party of Thai Counties: 1 seat | Fair: 1 seat | Plung Sungkom Mai: 1 seat | Thai Teachers For People: 1 seat

The Establishment’s Initial Attempts to disqualify the Move Forward Leader Pita

The Move Forward party is being subjected to this dirty “constitutional” process.

First, under the Constitution, the Election Commission (all members appointed by Prayut) are empowered to disqualify (even after the election) any MP-elect or candidate who is found to have failed to meet certain qualifications or in breach of certain prohibitions. At the time of this writing, the leader of the Move Forward party is accused of owning shares in a long-defunct ITV, a mass media company, whose business and broadcast rights were suspended 16 years ago. In fact, the shares, which amount to the mere 0.0035% of the company’s total shares, were inherited from Pita’s late father. The party leader was declared by a court to be the authorized heritage manager.

Yet, the allegation that Pita owns the shares in a media company is being investigated by the Election Commission. If the Commission rules that he indeed owns the shares, the case could be brought to the Constitutional Court. And if the Court affirms the Election Commission’s ruling, Pita could be banned from holding public office for as many as 20 years. Worse, he could end up in jail for up to 10 years, if convicted by a court of justice, though the chances of such criminal conviction seem very remote.

Even if he is cleared this time by the Election Commission and the Constitutional Court, there is no guarantee that no other challenges on his other election-related qualifications will be brought to the Court. The Constitution in fact allows anyone and at any time to bring such a case to the Court.

Again, even if the party leader is cleared by the Constitutional Court on all matters relating to his qualifications, the Move Forward leader still has to face a huge hurdle in terms of obtaining a majority of bicameral votes required to be elected as Prime Minister in the 750-seat joint chambers in the Thai Parliament. As of now his coalition of eight parties including Puea Thai has secured 313 seats. That number is still 63 seats shy of the necessary 376 seats. It is no easy task to fill the needed 63 seats. He needs either to convince Prayut-appointed senators to shift their stances in his favor or to seek support from MPs in the Prayut-led Axis to do likewise. Neither scenario seems possible.

As of now, the Move Forward party appears determined to try its luck, doing everything possible to form a coalition government with its leader Pitaa being Prime Minister.

What are the scenarios for Move Forward? What are the implications of the election-losers forming the next government?

However, I am not optimistic about the Move Forward’s chances of becoming the next government. In fact, the scenario of Move Forward leading a coalition is least likely, given the fierce opposition from the people currently in power, or the Establishment. The latter have vast quantity of resources, networks, and institutional means which will enable them to block the formation of the Move Forward-led coalition government.

In my view, the following two scenarios are far more likely to materialize.

In the first scenario, Puea Thai, the second biggest party, is instead allowed to lead a coalition, with Move Forward being allowed in the coalition. This scenario will emerge if Move Forward leader, Pita, is declared disqualified by the Constitutional Court. And the Parliament will have to nominate a Prime Minister candidate from Puea Thai. I would speculate – I could be way off the mark here – two things: 1) the country’s Establishment would not antagonize the public to the point of not honoring the election results at all and 2) it would find Puea Thai more palatable, thus allowing senators to vote for a Puea Thai Prime Minister candidate.

My own view, again, is that the “deep state” in Thailand would find it a compromise in order to prevent a potential confrontation and violence that could plague the country in the event that Pita is eventually disqualified.

Second, given how blatant these people (in power) could act, I still anticipate another scenario – I hope to be proven wrong though –wherein the losing axis of Prayut and cohorts simply disregard the will of the people as expressed in the polls by going ahead with their own coalition. In this scenario, the incumbent would urge the 250-appointed Senators to vote for Prayut or someone in Prayut’s camp to be the next Prime Minister. By the number, this could be accomplished easily, as the Prayut axis now have188 MPs in their camp. All they need is 188 out of 250 Senators to meet the 376 requirement.

What would likely happen out of this scenario is as follows: 1) Thailand could have a new Prime Minister but he is unlikely to form a coalition of his own, as a coalition that would be able to stand would need a majority of seats in the House. In that case, we could have both Prayut as caretaker Prime Minister and a Prime Minister Elect who would not be able to actually head a government. That would create a really bizarre situation, which could undermine the public confidence at home, and foreign investors’ confidence, thereby thrusting the nation’s economy into a deeper abyss; and 2) Thailand could have a minority government and later, perhaps, in a month or two, dissolves the Parliament and calls a snap election, to let the people decide again.

However, there exists clear risks for the Establishment choosing these anti-democratic scenarios. Both scenarios will most certainly outrage voters, who might decide to take to the streets, reigniting the cycle of mass protests, open and violent confrontations, even bloodshed and further damage to the society at large, the national economy and the key institutions of the country.

Thai student protests in Bangkok, July 18, 2020, showing three fingers against dictators. Wikipedia Commons

When are we going to see any of these scenarios?

By the Constitution, the Election Commission is allowed up to 60 days to officially endorse election results. Judging from the previous elections, it generally takes them up to 45 days to endorse and certify the election results. That means roughly by the end of June or a bit earlier, they will likely endorse the results.

After the official endorsement of the election results, the Constitution allows up to 15 days to convene the inaugural session of the Parliament during which the Speaker of the House is elected. This could take place around mid-July.

Following the appointment of the Speakers, a week or two comes the session to vote on Prime Ministerial candidate (s). This should come around the end of July or early August.

In the meantime, the Election Commission should conclude their investigation and deliberation on the Mover Forward leader’s qualifications. It is expected that the commission’s ruling could be reached roughly by mid- to late July. And the case could then be brought to the Constitutional Court by more or less about the same time as the parliamentary voting on the Prime Minister candidate(s).

Even if the Constitutional Court is yet to decide on whether or not to suspend Pita, pending their deliberation, the (appointed) senators would find some justifications not to vote for him. Or if Move Forward and Puea Thai could agree by then whether or not they should nominate Puea Thai Prime Minister candidate instead of Pita, senators under the guidance of the people in power, behind the scenes, would then decide if they would go for the second or third scenarios.

This is likely to happen in early August. For now the Thai nation remains on the edge.

Damrong Kraikruan

Former Ambassador of Thailand to Malaysia (2015-18)

Banner: Bangkok, May 2023. Thailand Move Forward party held big election rally at Thailand-Japan sport stadium as number of supporters showed the support for the party. Photo:kan Sangtong, Shutterstock