International Impunity and Policy Failures lead to Myanmar as a Failed State

Since the universally opposed February coup that toppled the re-elected populist government of Aung San Suu Kyi, and subsequent violent implosion of Myanmar’s civilian bureaucracy and the multi-ethnic and multi-class society at large, one typically hears of UN, media and INGO discourses about Myanmar as a “failed” or “failing state”.

Crucially, for policy makers globally, this spectacular failure of Myanmar as a political state of UN and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – however one defines it – must be seen accurately for what it is: the mirror reflection of the categorical failures of the international policies, including “peace building”, towards the fundamentally military-controlled unitary state and the multi-ethnic society, or ethnic nations.

Myanmar: Not a “Failed State” Overnight

Myanmar: Not a “Failed State” Overnight

The established pattern of international impunity – which Myanmar’s criminal military regime has taken for granted – has resulted in this sordid affair in Myanmar, with continuing spill-over diplomatic, demographic and destabilizing impact on other neighbouring UN member states such as Thailand, Bangladesh, and Malaysia.

From the Security Council and ASEAN, the European Union, to the powerful external actors such as China and USA, the international community have failed to hold to account Myanmar as a UN member state, a business partner and a strategic ally, breaking multiple inter-state treaties including the Genocide Convention and committing crimes against humanity when citizen-journalists livestreamed the crimes being perpetrated against protesters, as well as children, women, innocent bystanders in broad day light.

2-Minutes Speech dedicated to Rohingya victims of Myanmar’s Genocide

To its credit, and regardless of its motives, the regional bloc of ASEAN has in effect acknowledged that the business-as-usual approach to Myanmar affairs is not working even in pursuit of its own group mission and the interests of individual members with varying degrees of military, strategic and commercial ties with Myanmar and its most powerful domestic actor – the military regime. The unprecedented exclusion of the coup junta head, Min Aung Hlaing, from this week’s ASEAN Summit of heads of states, is a radical break from the grouping’s founding principle of ‘Non-Interference’ adopted in 1967.

The Malaysian Foreign Minister has reportedly urged fellow ASEAN ministers to do some “soul-searching”, when he “stated the fact that we cannot use the principle of non-interference as a shield to avoid issues being addressed.”

Indeed, the business-as-usual approach towards Myanmar is no longer serving even the business interests of external actors. ASEAN members including Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia have substantial business ties with Myanmar, with Singapore leading the pact with its $24 billion trade and investment portfolio, in addition to serving as Myanmar military’s primary money-launderer.

In his official address to the ASEAN Summit today even Cambodia’s autocratic leader Hun Sen felt compelled to say that the coup regime’s “lack of cooperation” with the group will “regrettably” make “ASEAN-Minus One (that is, without Myanmar)” in the coming Asia-Europe Meeting.

Cambodia Prime Minister Hun Sen: #Asean-Minus-One #myanmar. (SAC junta leaders) have only themselves to blame – for being excluded from @ASEAN Summit. They will NOT be participating in the coming Asia-Europe Meeting, if they continue to travel this route of non-cooperation. Image: Myanmar Now Facebook

Myanmar Coup Triggers Societal Implosion

Against the backdrop of the political implosion is the vast mafia-like economy, in the hands of the military conglomerates, a handful of cronies and families of the military general ranks, interlocked with several localised regional war economies that rest on extractive industries (jade, gold, timber, etc), human and drug-trafficking and cross-border trade overseen by different ethnic armed organisations or EAOs.

A recurring feature of international Myanmar policy regimes, sanctions or engagement, or a variation of the two, over the last several decades, is the apparent failure to appreciate, and take into consideration, local knowledge or interpretations of Myanmar political and economic affairs. There have been no shortages of empirical analyses generated by local activists rooted organically in the civil society and by those of us independent scholars, who pin our ears to the Myanmar ground.

It suffices to say that international actors, including the UN official and politicians and policy makers in influential world capitals, have consistently ignored local Burmese scholarship – including my own – and other critical policy briefs and analyses that sounded early warnings on the genocide, the inconceivability of genuine change through the 2008 Constitution of, for and by the military, the deeply mafia-like criminal nature of the country’s national armed forces and last, but not least, the failed leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi. As evidenced in the now UN and INGO narratives of “failed state” and “civil war”, international policy-failures have catastrophic consequences for the Burmese communities. The genocide of Rohingyas, apartheid-style citizenship based on “blood” and faith, decades-old patterns of war crimes in non-Bama ethnic minority regions, and crimes against humanity against civil society activists and journalists, extractive-industry-linked internal displacement of farmers, villagers and workers spring to mind.

Seeing Myanmar Affairs through Local Eyes, Listening to Local Voices

Moving forward, policymakers and advocates must own their past mistakes, intellectually and morally. They must come to terms with the fact that repeating their tried and failed approach of ignoring local perspectives, and imposing their solely self-interest-driven, or misguided “Myanmar policies”, under new spins, will not produce the policy objectives of stability and peace. At the bare minimum, stability and peace in Myanmar are universally shared amongst important external influencers, albeit with divergent interests, such as China, USA, EU, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Japan.

Importantly, it bears pointing out that the newly emerging policy framing of Myanmar’s revolutionary implosion as “civil war” still doesn’t quite capture accurately the deeply troubling cluster of developments on the ground.

Civil war in Myanmar is nothing new: with fluctuating intensities, it has been raging over the last 70-years.

The then, newly independent Union of Burma, under the civilian and multi-ethnic leadership of Prime Minister U Nu, plunged into a civil war with the two successive “insurrections” – first by the Communist Party of Burma, with the mutiny of a significant number of troops led by communist-sympathising commanders, including ranking military leaders, in less than 90 days of independence from Britain in January 1948, and subsequently, by the Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO), or the precursor of the Karen National Union and its armed wing Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA).

In a nutshell, what is presently lumped under the label of “civil war” in Myanmar as a “failed and failing state”, are two interlocking phenomena: ethnic minority rebellions, ongoing, and the total revolution by the dominant society – political class, to be exact.

These two cannot be reduced to the single label of a “civil war”.

The Two Myanmar-s: Ethnic Rebellions and Majoritarian Revolution

The categorically unbalanced or slanted narratives about Myanmar, be they minority-focused, or the state-centric and ethnic-majority-driven analyses and policy advocacies, have missed the seasaw like the “center-periphery” quagmire: pro-minority discourses placing “tribal” or provincial group interests (via the representation of the Ethnic Armed Organizations in ceasefire talks) above the ethnic majority’s concerns for democratic or basic human rights while the majority advocates (for instance, NLD and Aung San Suu Kyi), pushing for majoritarian democratic transition and monopolizing international policy discourses (for instance, “fragile democratic transition” and “democratic elections”, typically and predictably won by the ethnic majority) have without fail only played into the straightforward divide-and-rule hands of central perpetrator of all crimes against Myanmar people, namely the successive military regimes since the civil war broke out upon independence.

The categorically unbalanced or slanted narratives about Myanmar, be they minority-focused, or the state-centric and ethnic-majority-driven analyses and policy advocacies, have missed the seasaw like the “center-periphery” quagmire: pro-minority discourses placing “tribal” or provincial group interests (via the representation of the Ethnic Armed Organizations in ceasefire talks) above the ethnic majority’s concerns for democratic or basic human rights while the majority advocates (for instance, NLD and Aung San Suu Kyi), pushing for majoritarian democratic transition and monopolizing international policy discourses (for instance, “fragile democratic transition” and “democratic elections”, typically and predictably won by the ethnic majority) have without fail only played into the straightforward divide-and-rule hands of central perpetrator of all crimes against Myanmar people, namely the successive military regimes since the civil war broke out upon independence.

On one hand, there is the decades-old existence of ongoing ethnic armed rebellions by the non-Bama ethnic nationalities (who make up, perhaps, up to 40% of the country’s total population of 50+ million). These non-dominant ethnic nations, or communities, have their own distinct languages, cultures, ethnic/regional identities, political histories, historical memories, and localised “war economies”. Scattered in different geographical regions, these nations operate under the loose leaderships of what is referred to as variously sized, “ethnic armed organisations, or EAOs”, located in strategic border regions adjacent to Thailand, Northeast Provinces of India, Bangladesh, China, and Thailand.

What compounds the politics and the label of “ethnic nationalities” (that is, minorities) is the active intra-minority military conflicts, or “horizontal turf wars”, over political and cultural representation and geographic and economic turfs (e.g., Christian Chin – Buddhist Rakhine and Rohingya – Rakhine conflicts in Western Myanmar; Shan vs Ta’ang armed resistance groups over political representation and cultural repression, and intra-Shan armed organisations, over economic and territorial gains in Eastern Myanmar; the Kachin armed organisation and the Red Shan group in Northern Myanmar).

On the other hand, there is the dominant Burmese society at large, that have launched what the majoritarian public consider a ‘Zero-Sum Revolution’ or ‘Existential War’ – no less – against the country’s Bama, or Burmese-controlled, or -focused central military force, known as Tatmadaw. This Nwe Oo Revolution of the pro-NLD dominant Bama in the ethnic heartlands of towns, cities and villages, is led by white collar-class of professionals (doctors, engineers, university students, accountants, poets, journalists, bankers, performing artists, etc.) who either join the Civil Disobedience Movement, designed to hollow out the civilian bureaucracy now under the coup regime’s control, join various armed ethnic organisations in hope of military training, or set up local militia groups with the view towards waging an urban guerrilla warfare. Additionally, labour organisers and networks in the country’s growing textile and garment manufacturing sector have also joined this mainstream society’s revolution.

On the other hand, there is the dominant Burmese society at large, that have launched what the majoritarian public consider a ‘Zero-Sum Revolution’ or ‘Existential War’ – no less – against the country’s Bama, or Burmese-controlled, or -focused central military force, known as Tatmadaw. This Nwe Oo Revolution of the pro-NLD dominant Bama in the ethnic heartlands of towns, cities and villages, is led by white collar-class of professionals (doctors, engineers, university students, accountants, poets, journalists, bankers, performing artists, etc.) who either join the Civil Disobedience Movement, designed to hollow out the civilian bureaucracy now under the coup regime’s control, join various armed ethnic organisations in hope of military training, or set up local militia groups with the view towards waging an urban guerrilla warfare. Additionally, labour organisers and networks in the country’s growing textile and garment manufacturing sector have also joined this mainstream society’s revolution.

Myanmar Majority’s Political, Social and Violent Revolution

This is a very radical departure, in that the dominant Bama public had shared this Burmese-centric ethnonationalism towards the rest of other ethnic nations such as Rakhine, Shan, Kachin, Mon, and so on, as well as non-Buddhist faith-based communities of Christians, Hindus, and Muslims. This is despite the fact the dominant ethnic Bama Buddhist public, too, have suffered under the boot since the military officially instituted the one-party military state since March 1962. To be sure, the majority public have only recently experienced the level of brutality and cruelty which the minorities have endured for decades since independence: the military has only recently begun to resort to sexual violence and “the Four Cuts”, or scorched earth policies, in urban neighbourhoods and villages in the majority heartlands.

Painfully for me, it bears pointing out that as late as 2019, the Aung San Suu Kyi-led Burmese public had “stood with” the military, as the latter carried out vicious military operations in Kachin and Rakhine states where the troops were perpetrating genocide against Rohingyas, war crimes and crimes against humanity against Buddhist Rakhine communities supportive of the Army and the Kachin Independence Organisation.

Post-coup, the sentiment of the Myanmar public regarding their national military, has undergone an irreversible and seismic transformation. The prevailing public opinion in Myanmar today is bitterly and categorically opposed to any form of the generals’ future involvement in the country’s political and economic affairs.

Unlike ethnic nationalities’ armed organisations which have engaged in negotiating with the central military in the latter’s on-again, off-again “peace process”, the dominant Bama public no longer view their ethnic Bama brethren in generals’ uniform as dialogue partners to negotiate with, for the people’s freedoms, human rights, or democratisation. Perhaps more radically – if only accurately – the dominant public commonly perceive generals and the military as a Fascist-like occupying force that must be expelled, or destroyed, by any means necessary.

Both conceptually, and linguistically, the majority Bama public intentionally stopped using the word “Tatmadaw”, or the royal, or feudal military, lest the usage connotes any semblance of public acceptance and, conversely, acceptability of the formerly national military as a legitimate armed group. Last Friday, U Kyaw Moe Tun, who remains as Myanmar’s permanent representative at the UN, to the UN General Assembly committee, said “(i)n the eyes of the people of Myanmar, the military is more like an occupying force, not a protector of the people like it’s supposed to be.”

From Rebellions vs Revolution to Rebellions AND Revolution

This crucial difference between the ethnic minorities’ rebellion and the Bama or Burmese majority’s total revolution will need to be considered at the centre of the new attempts to find resolutions to the already-protracted civil war of 70-years and the unfolding anti-military revolution of the majority in its early days.

In his Introduction to “Revolutions: How They Changed History and What They Meant Today”, a collection of concise analyses of 24-different pre-modern and modern revolutions dating back to the English Revolution of 1642-1689, Peter Furtado, former Editor of History Today, writes, helpfully, “(a) revolution is often contrasted with a rebellion – not only in that a revolution succeeds in its immediate aims, whereas a rebellion probably fails, but in its choice of aims as well. The rebel typically seeks autonomy from the tyrant, whereas the revolutionary seeks to overthrow them (p.9).”

Over the last 30+ years, I have intimately been involved in Myanmar’s political affairs, supporting, and joining different policy regimes – sanctions, engagement, and everything in-between, depending on shifting realities on the ground. Additionally, as a professional student of Myanmar affairs, I specialise inter alia in Myanmar military affairs. I have never seen any anti-military movement which fits the textbook definition of a revolution until the current New Oo Revolution of Myanmar. A vast professional class of white-collar workers, and a new generation of youth, now share the single strategic conclusion that the Tatmadaw, or national army, with its Fascist-DNA and a mafia-like grip on national economy, must be destroyed for the people to have any future.

Neither the dominant society, nor the militias which have mushroomed, have shown any desire for negotiations with the coup regime that is committing crimes against humanity in the heartlands of Myanmar majority, as well as in select ethnic minority regions, such as the Chin and Kayah states. The regime has also closed off any venue, or space, for peaceful protests and negotiations with the anti-coup society and political actors. For the revolutionary groups popularly backed by the society at large, the Burmese military has irreversibly morphed into a terrorist syndicate.

No Dialogue and More Bloodshed: Coup Regime Ruled Out Inclusive Dialogue

On its part, and against the backdrop of ASEAN’s unprecedented blow of Summit exclusion, the junta has declared that it “cannot accept … dialogue and negotiation with terrorist armed groups” – as recently as 24 October.

Even if the coup junta, under Min Aung Hlaing, were open to an inclusive dialogue, which he had himself agreed to, as part of the ASEAN’s Five Point Myanmar Consensus at the face-to-face meeting in Jakarta in April, even a cursory glance at the nearly 60-years of “negotiations” and “peace talks” with Myanmar military, speaks volumes about the futility of talking to a Fascist-like mafia drunk with its own might. (The New York Times)

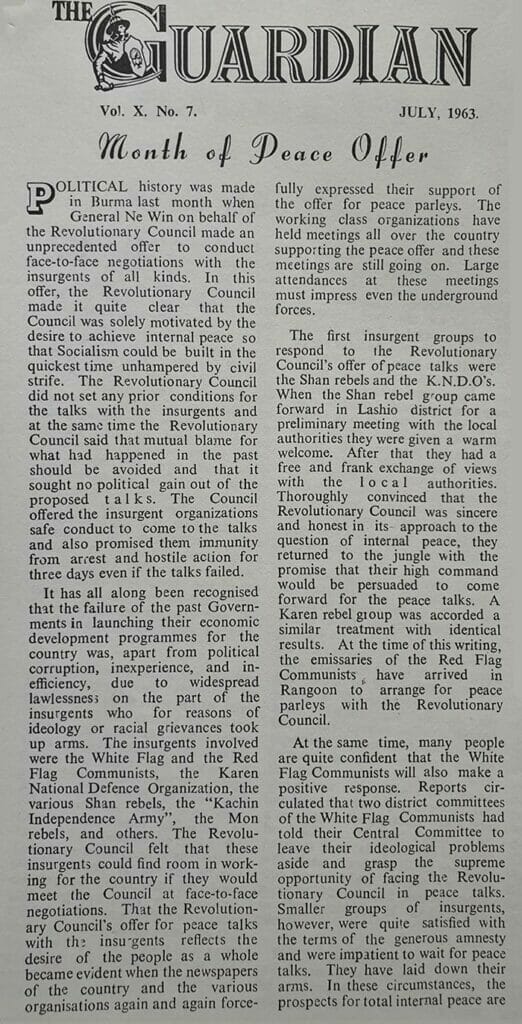

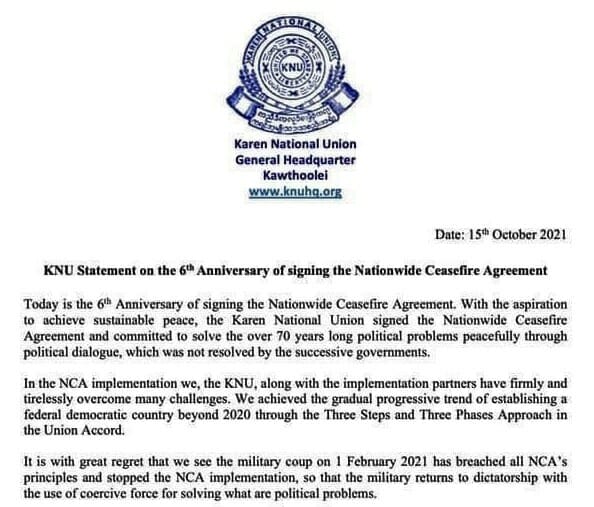

Since 1963, when the original military dictatorship of General Ne Win launched the military’s “Peace Negotiations”, with the then existing half-dozen armed organisations, including Shan, Mon, Karen, Kachin and the Burmese communist underground, the military has shown absolutely no desire to compromise, or negotiate, “its terms of peace”. As to be expected, the number of armed ethnic resistance movements and organisations has only multiplied 4-fold since the military’s first peace and ceasefire talks in 1963. The country now has about 2-dozen armed organisations, with different troop strengths, with criss-crossing turf and territorial disputes. Some of the largest, or most significant armed groups, (Arakan Army, Kachin Independence Army, United Wa States Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Chin National Front, Karenni National Progressive Party troops, and the strongest brigades of the Karen National Liberation Army) are serving as enablers to the newly emerging urban guerrilla groups with their avowed revolutionary aims.

Ne Win is no more, and neither are the representatives of ethnic armed organisations, who came for “peace talks” in Rangoon. But the military’s “peace” paradigm – “peace-only-on-our-terms” – has long been institutionalised by the successive generations of the Burmese military officer corps. Today’s generals continue to view themselves as the sole class of patriots whose armed organisation is the sole non-partisan, genuinely national organisation, guarding the interests of the Union of Myanmar, despite all evidence to the contrary. It views any group, armed or non-violent, majority Burmese, or ethnic minorities, that challenges its acts of usurpation and monopolistic grip on the country’s political power and economy, as “terrorist”.

Against this background of bitter political opponents ruling out any dialogue, even the UN Special Envoy to Myanmar, Christine Schraner Burgener, hardly managed to conceal where her sympathies lie. In her final official press conference, as the outgoing diplomat whose mandate ends at the end of this week, the Swiss ambassador urged the world to support the people of Myanmar – in revolt.

Going all the way back to the 18th Century Conservative critics of revolutions and violent rebellions such as Edmund Burke, the concerns about the bloodshed and the excesses of revolutions are valid and need to be taken into full consideration when new policies towards the failed state of Myanmar are explored. No policy advocate or policy-maker in his or her right might would debate about negotiations and mediations as the preferred and preferable option for Myanmar peoples.

Paraphrasing Nelson Mandela, who, condemned by the West as “a violent Communist” or “terrorist”, spent 27 years behind bars for leading the armed revolution against the intransigent apartheid regime in Pretoria, sometimes the oppressed do not have the luxury of choosing non-violence. For Myanmar people, the only ethnic group, without their own “ethnic armed organization”, who could negotiate with their oppressor, the national military, at the ceasefire negotiation table, this venue for non-violence is foreclosed by Min Aung Hlaing’s coup regime.

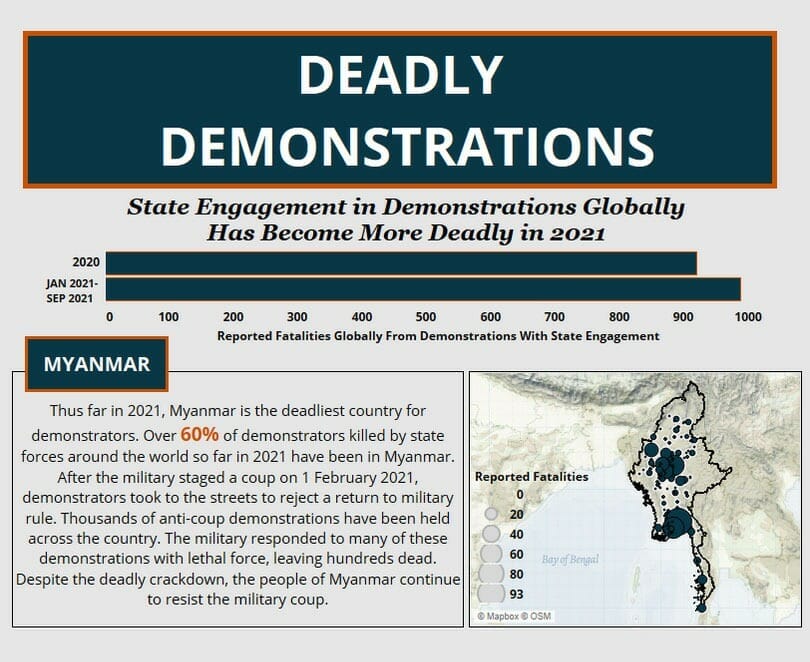

Deadly Demonstrations: Fatalities From State Engagement on the Rise. Graphic from ACLED

Myanmar since the coup is home to the 60% of the total number of (peaceful) pro-human rights protesters killed worldwide. Last week, Christine Shraner Burgener, the outgoing Special Envoy of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, told the United Nations, that “the repression of the military has led to more than 1,180 deaths. The army uses a range of tactics against civilian populations, including burning villages, looting properties, mass arrests, torture and execution of prisoners, gender-based violence and random artillery fire into residential areas.”

A decade ago, when I was chasing high-value Myanmar military defectors throughout Southeast Asia for my research into the inner workings of the country’s most powerful criminal syndicate – namely the Tatmadaw or armed forces – I held meetings with the Asian soldiers who knew their Myanmar counterparts intimately. In his office in Manila, ex-President Fidel V. Ramos remarked that the then military dictator Senior General Than Shwe, with whom he played golf in Rangoon and Manila, “he is very tough.” More prophetically and ominously, one Indonesia General who just returned from Naypyidaw from the meetings with Than Shwe’s deputies, pointedly told me over dinner in Jakarta in July 2010, “your country is NOT going to change without serious bloodshed”. In other words, Myanmar generals would not relent, without a bloody fight.

Of course, “whose blood?” is a separate and additional question conscientious policy advocates and policy-makers will need to ask. Nine months on since 1 February coup, the anti-coup movement, has morphed from an entirely peaceful and non-violent protests in virtually all corners of Myanmar, into a violent, full-blown revolution. The young generation of Burmese – Generation Z – and the generation that came before – have decided that they would rather forego the joy of middle-class life – education, career, families, leisure and so on – and, importantly spill their own blood.

Again UN Special Envoy on Myanmar pointed out the inseparable link between the violent revolution and the failed international community: “Clearly, in the absence of international action, violence has been justified as the last resort.”

It is this vicious cycle of “Failed Policies, Failed State” that must be broken.

This dialectic of “failed international policies AND failed Myanmar state”, will need to be placed at the right, left and centre of the new international policy debates on Myanmar. Repeating the same strategy of dangling the sweet discourse of mediation before the intransigent mass-murderous generals of Myanmar without the stick of international accountability will not do.

Maung Zarni